Proportional Representation Is a Terrible Idea That The Left Should Not Embrace

The electoral road is never easy for the left, but an electoral system that forces coalitions as a matter of procedure only makes things worse.

Under conventional American electoral rules, the candidate who gets the largest share of the vote in a given constituency wins. This is called “first past the post,” or FPTP. If you get 25 percent of the vote, but another candidate gets 30 percent, the candidate with 30 percent gets the whole seat and you get nothing. Some on the left advocate for electoral reform, especially proportional representation, to make it easier to develop a third party alternative to the Democratic Party at both the state and federal levels. Under proportional representation (or PR), political parties win a number of seats that is proportionate to the share of the vote they get. If you win 25 percent of the vote, you get 25 percent of the seats, even if there is no part of the country where you command a majority or even a plurality. This lowers the barriers to political entry and helps small parties get started. As DSA members Neal Meyer and Simon Grassmann wrote in Jacobin:

Overcoming the two-party system and transitioning to a system of proportional representation is of paramount strategic importance for the socialist cause. Our ability to win—and to base a future socialist government on the support of the majority of society—would be greatly aided by this transformation.

The attraction is understandable. Under PR, left-wing third parties would win more seats in Congress than they do under the two-party system. Left-wing politicians wouldn’t have to run as Democrats to compete. If the left didn’t have to run in Democratic Party primaries, it could run on its own platform. It wouldn’t have to explain to centrist Democrats why being left wing is strategic. It wouldn’t have to find a way to command pluralities and majorities in conservative red states. It could be principled. It all sounds great, but it’s not. Here are a few reasons why.

Party Proliferation

Because PR lowers barriers to entry, it’s possible for left-wing parties to get off the ground. But there is little reason for left-wing parties to stay together, because it’s easy to start new competitive parties. This means not only that the existing parties—like the Democratic Party— splinter, but that new parties also struggle to stay together. The number of parties expands. Particular parties also become politically isolated from one another and from the general public. When parties can secure seats in the legislature by speaking to small percentages of the electorate, there is a strong incentive to specialize, to focus on some small part of the electorate, instead of the working class as a whole. Big, catch-all parties tend to lose voters to these smaller, more specialized parties. Over time, the bigger parties tend to break down, and you get large numbers of small parties catering to niche audiences. The more they do this the harder it is for them to build broad public support for their policies.

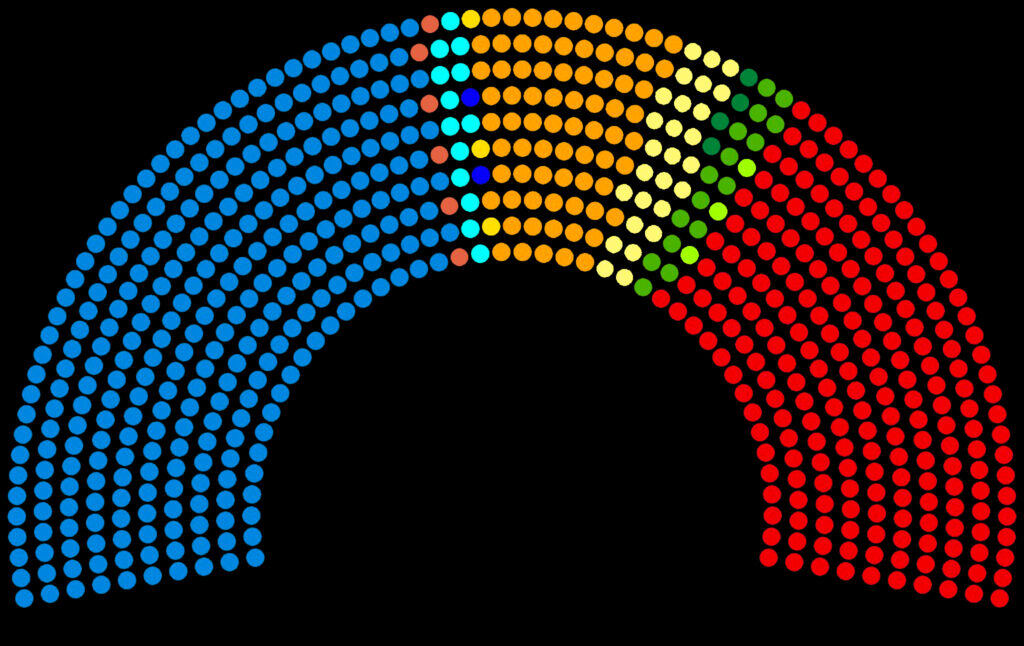

In the Netherlands, there are many parties. Often, they focus on very narrow, specific slices of the electorate. In the lower house, there are 16 different parties, and even in the upper house, there are 14. There’s a party for democratic socialists, a party for social democrats, a party for environmentalists, a party for social liberals, a party for conservative liberals, a party for liberal conservatives, a party for economic liberals, two distinct parties for Christian democrats, a couple of right-wing populist parties, a party for Calvinists, a party for people who care about animal rights, and a party specifically for people over the age of 50. The last time any of these parties won more than 30 percent of the vote, the year was 1989.

The large number of niche parties makes it impossible for any party to govern alone. This means there are always coalitions. Germany limits the number of parties by insisting that parties receive at least 5 percent of the vote before they receive representation. But even in Germany, there are half a dozen different parties with seats. Since World War II, not one German chancellor has governed without a coalition. Some people think coalitions are just dandy—after all, they ensure that legislation can only be passed with the support of a majority, and under PR, a legislative majority always reflects an electoral majority. British socialist Ralph Miliband had no problem with them:

Labour supporters of the first-past-the-post system argue that it also gives the Labour Party a chance to win an election and form a government of its own. This may be true, but it ignores some important facts, quite apart from the point of principle that the electoral system should not greatly distort representation. One fact the argument ignores is that a government engaged in fundamental reform needs a much greater measure of support in the country than does a conservative government. It is only thus that a radical government could hope to achieve its purposes; and that support ought to be reflected in voting figures. Fifty-one percent is no magic figure; but achieving that figure, alone or if need be in coalition, is nonetheless very helpful.

Unfortunately, coalitions don’t work this well in practice. While it may sound fair or legitimate to require that the left wing more than 50 percent of the vote, this rule introduces an enormously powerful status quo bias into the political system. Let me show you how coalitions work—or, rather, how they don’t.

Campaigns versus Coalition Agreements

In a system where coalitions are inevitable, parties are never able to keep all of the promises they make during campaigns. When they join coalitions, they have to sign coalition agreements, and in these agreements, they make concessions on many issues so that the government will be cohesive and stable. In practice, this means that parties make many promises on campaign trails, for the purposes of attracting voters, that they know they will never be able to keep. Once they are in government, they claim it was necessary to break the promises to make the government solid. The voters can never be sure whether this is true. For all they know, the “left-wing” party only took left-wing positions in the campaign to give itself leverage in coalition negotiations. The party manifestos become meaningless campaign documents. They no longer credibly promise anything, and they cannot be used to hold the parties responsible for what they do. This is precisely the way the Democratic Party behaves. It makes promises during campaigns it has no intention of keeping, and it often governs through bipartisan cooperation with members of the Republican Party. But under PR, coalitions are baked into the system through the electoral law. This makes them procedurally inescapable.

In 2010, Britain had an election that ended in a “hung parliament,” where none of the parties obtained a governing majority. Britain operates under FPTP, but still got a coalition because the electorate was so heavily divided. It was the first hung parliament in 36 years, and only the second coalition government since World War II. The Conservatives got 47.1 percent of the seats on 36.1 percent of the vote, while Labour got 39.7 percent of the seats on 29 percent of the vote. The Liberal-Democrats were only able to translate their 23 percent of the vote into 8.8 percent of the seats, but this still left them holding the balance of power. They could form a minority government with Labour, to keep the Conservatives out, or they could form a more stable government with the Conservatives. During the campaign, the Liberal-Democrats promised to “scrap unfair tuition fees.” But ultimately, they chose to go into a coalition with the Conservative Party and break their promise. They not only failed to abolish tuition fees, they failed to lower them, or even to leave them where they were. They stood idly by while Prime Minister David Cameron and company raised fees. The Liberal-Democrats did this for the Conservatives in exchange for a referendum on electoral reform. Having demonstrated so effectively that coalitions are terrible, it was no surprise that the Liberal-Democrats went on to lose the referendum badly. The Liberal-Democrats abandoned university students for an opportunity to rig the electoral system in their favor, and they couldn’t even manage to get that done. Then they made a cheesy video. They apologized for breaking their promise while slyly suggesting they had no choice but to break the promise for political reasons.

Their supporters still argue that they had no choice, and Liberal-Democrats still argue that going into a coalition ought to be considered a form of “winning.” That brings us to the second problem with coalitions.

Unreliable Partners Make Winning Impossible

It is often assumed that in coalition agreements, the larger parties will dominate. The Liberal Democrats were the junior partner in 2010. What if a large left-wing party were the senior partner? The trouble is that even when the left-wing party is the senior party, it still usually has centrist parties in its coalition. These centrist parties will sink the government if they feel it is making economic reforms that seriously undermine capitalism.

In Britain in 1929, the Labour Party formed a government in coalition with the Liberal Party. The Great Depression should have given a Labour government an opportunity to enact bold reforms. But instead, the government’s creditors put intense pressure on the government to maintain the Gold Standard and keep the budget balanced. The Liberal Party helped apply this pressure, and some Labour politicians even cooperated. Eventually the government fell apart over a proposal to cut unemployment benefits to balance the books. In the national government that followed, the Liberals continued to participate, the Conservatives were invited in, and the left was shut out. Labour did not win again until 1945.

Going into coalition can feel like winning if you’re a centrist who wants to trim around the edges, but for leftists looking to deliver transformative change, coalitions are a swamp. Proportional representation ensures that left-wing parties rarely enter government without at least one centrist party around to throw sand in the gears. Since World War II, there has never been a left-wing government in the Netherlands. Social Democrats have governed the Netherlands for about two decades out of the last seven with the support of overtly centrist parties with liberal or Christian Democratic orientations. In the same period, the Social Democratic Party never governed Germany without the support of the liberals or the greens, and both of those parties are firmly committed to the market system.

These centrist parties are capitalism’s watchdogs. They keep an eye on left-leaning governments and ensure they don’t step out of line. They heavily limit what left-wing governments can do. Left-led coalitions function as if they were the Democratic Party. No matter how big the left is, it is the centrists within the coalitions that ultimately determine what left-wing policies get through. If they don’t get what they want, these centrists cooperate with the right to destroy left-wing governments.

In Spain, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez approved the outgoing Conservative Prime Minister’s budget to get the support of the Basque Nationalist Party. Regional parties like the Basque National Party are elected in part to secure public investment for their regions, and they will always consider defecting to the right if the right offers more cash. Often these regions have been economically neglected, and the people who live in them are badly in need of state aid. It would be unfair to expect regional parties to behave any other way. And yet, under PR, we are forced to bet on the loyalty of parties that, all too often, have every reason to defect when the going gets tough. Because of its reliance on small regional parties, Sánchez’s minority government isn’t in a position to implement radical economic reforms. It quickly retreats whenever it meets resistance or gets into trouble. Sánchez has previously positioned himself as a centrist at other points in his political career. Is he hemmed in by PR, or are his own convictions prone to change?

Under PR, there’s no way to know for sure. People believe what they want to believe about him. If you want to think that there’s a cool left-wing government in Spain, then you talk yourself into the purity of his intentions and you blame the other parties for frustrating him. If you want to be cynical and argue that he’s playing games, you can just as easily talk yourself into that, too. In reality, PR ensures that the left cannot achieve a real victory in Spain, regardless of who leads it or how it is organized. The left will always operate a minority government or rely on the support of disloyal small parties. Sometimes, it will operate a minority government while also relying on the support of disloyal small parties, as it does now.

A Ghetto for the Left

In Germany, there is a left-wing party that has never been in coalition. It’s called Die Linke, “The Left.” Linke is committed to democratic socialism, but is descended from the East German Socialist Unity Party. Most of its votes still come from the East. Because Linke is associated with the East German government, German capitalists do not consider it trustworthy. In 2013, Linke came third in the German federal election. The Social Democrats had the opportunity to see off Chancellor Angela Merkel by joining with Linke and the Greens. But the Social Democrats declined. Instead, they joined a Grand Coalition with Merkel’s center-right Christian Democratic Union.

Because everyone in Germany who is really left-wing has the option to join Linke, there aren’t very many committed left-wingers in the Social Democratic Party. This has enabled the Social Democratic Party to become more centrist over time. There is nothing particularly left-wing about the German Social Democrats at this stage. The last Social Democratic chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, is the chairman of the board for Nord Stream AG. Nord Stream transports Russian oil and gas to Germany. He’s also chairman for Rosneft, a Russian oil conglomerate. The Schröder government was responsible for the Hartz labor market reforms. These reforms reduced unemployment benefits, made it much easier to fire German workers, and dramatically increased the number of German workers who are precariously employed. The Hartz reforms have kept Germany’s labor market competitive, giving Germany a competitive advantage when trading with countries like Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece. These countries face constant pressure to enact similar reforms to remain economically competitive. In the long run, the Hartz reforms may be the harbinger of doom for the entire European social system. The German Green Party was happy to support Schröder’s government and the Hartz reforms, because it is also completely useless to working people.

Only Linke offered opposition. But the PR system in Germany has turned Linke into a ghetto for left-wing people, keeping them out of politics. Linke has no chance of going into government. Because of this, ambitious young Germans steer clear of it, joining the Social Democrats or the Greens instead. Once they are inside these parties, they are swiftly integrated into centrist social networks and learn to love the Hartz reforms for making the German economy strong. Increasingly, German voters see that voting for Linke is pointless, and its vote share is now less than half as large as it was in 2013. During the same period, the British left fought tooth and nail for its position within the Labour Party. It succeeded in installing Jeremy Corbyn as leader. While Linke declined and the German left wandered in circles, the British left made a serious play for power. It is true that Corbyn was ultimately ousted after five years and the new leader, Keir Starmer, is doing everything he can to marginalize the left within the Labour Party. But first-past-the-post keeps open the possibility that the left may yet turn things around, while proportional representation forever shuts that door. Few expected Corbyn to win in 2015, or for a party led by Corbyn to win 40 percent in the 2017 general election.

The electoral road is never easy for the left, but an electoral system that forces coalitions as a matter of procedure only makes things worse. Coalitions allow parties to lie about their intentions. When left-wing parties are included in coalitions, they rarely get what they want out of them. When left-wing parties are serious about getting what they want out of coalitions, they are excluded from them. But this is just the start of the trouble with PR.

Non Dynamic Democratic Institutions

At first glance, PR looks like it makes democracy more responsive. After all, the parties that people vote for actually get represented. Surely, this is more representative than first-past-the-post, where parties that get votes don’t get represented? If only it were that simple. Because PR produces coalitions, it becomes very hard to use elections to produce radically different governments.

Say we have three parties, a left party, a centrist party, and a right party. None of the three parties ever win a majority, because all three have evolved to satisfy distinct electoral bases and PR prevents any one of the three from translating an electoral plurality into a legislative majority. This means you can in theory get six governments. Four of the six are realistic possibilities, and all four include the center:

- A government with the left as the senior partner and the center as the junior partner

- A government with the center as the senior partner and the left as the junior partner

- A government with the center as the senior partner and the right as the junior partner

- A government with the right as the senior partner and the center as the junior partner

The only way to keep the center out is to do a coalition of the left with the right—an unlikely possibility, and something few on either side want to see. Since the center is always part of the government, the center is always the limiting factor regardless of how people vote. In every government that is possible, the center will be able to veto policies it doesn’t like. This greatly limits the range of practical policy making. PR allows for lots of different electoral options, but it produces non-leftist electoral results every time. Under PR, you may be able to order a dozen different things off the menu, but the system serves you chicken nuggets every time.

This means that under PR, things tend to stay the same. If you like the status quo, this is great. A lot of people on the left like post-war social programs. In countries with first-past-the-post, right-wing governments under leaders like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were able to quickly do permanent and irreversible damage to social programs. If you have PR, it’s harder for the right to succeed in destroying the welfare state, because the right has little chance of forming a majority government that does not rely on the center for support. Today, the top 1 percent’s income share is a bit lower in the European countries with PR. These countries built their social systems many decades ago, and PR has slowed right-wing efforts to gut them.

But PR doesn’t facilitate change. In the United States, our social programs have already been badly eroded. There is little remaining for PR to protect. We need to make big changes quickly, and that’s not what PR is designed to do.

In the post-war era itself, the Anglophone countries benefited from their first-past-the-post systems. When Clement Attlee was elected Prime Minister of the UK in 1945, first-past-the-post gave his party a majority in the House of Commons. He was able to quickly implement a National Health Service in just a few short years, even though he was out of office by the end of 1951. Because he commanded a majority, he was able to make a true single-payer system. It proved so popular that even Conservative majority governments have been unable to destroy it. It is taking them decades to slowly defund and privatize it, and they are having to be very quiet and sneaky to avoid attracting too much attention.

If you look at the “post-war trough,” the moment when the top 1 percent’s income share hit its lowest level on record, the first-past-the-post countries stack up better. Only the United States looks out of place:

Some FPTP countries posted top 1 percent income shares that are competitive with those of the Soviet Union. Australia’s 5.6 percent in 1983 is identical to the Soviet Union’s top 1 percent income share in 1956 (Soviet top 1 percent income share bottomed out at 3.6 percent in 1980). Even today, Australia has the highest real inflation-adjusted minimum wage of any Western country, at $14.54 USD. Even the lowest paid Australian worker earns, in less than 20 minutes of work, enough to buy a Big Mac. For comparison, an American minimum wage worker needs to work for 34 minutes to acquire the same sandwich.

While it’s true that under FPTP you can get a Thatcher or a Reagan, you can also get a Gough Whitlam.1 Have you heard of him? Gough Whitlam was leader of the Labor Party in Australia, and he was elected Prime Minister in 1972. Whitlam created a national health insurance program and abolished university tuition fees. He frightened capitalists so badly that they turned to the British Governor-General to have Whitlam dismissed without an election. This led to a constitutional crisis. The left lost only because the Australian constitution left the Prime Minister formally subordinate to the Queen through her legal representative—the Governor-General.

Countries with PR have different kinds of constitutional crises. In countries with PR, the electoral system can thwart change so thoroughly and for so long that desperate voters turn to right-wing authoritarian solutions. It doesn’t always happen, but when democracies face very serious problems and are deeply divided about how to solve them, it is more likely that PR will fail to produce a stable government. This can allow very serious problems to fester. If we come to think of democracy and PR as inextricably linked, the failures of PR can easily be associated with democracy itself. In the worst cases, this gets very grim. The Nazi Party grew in Germany through proportional representation. In 1928 it received just 2.6 percent of the vote, but after the Depression shook confidence in the government, it saw its vote share increase to 18.3 percent in 1930 and 37.3 percent in 1932. For a time, other parties refused to cooperate with the Nazis, forcing further elections. But the Nazis still won 33.1 percent in November 1932. PR prevented Hitler from translating these vote shares into a governing majority, but it also prevented any other functional government from forming. Eventually, seduced by the need under PR to find a stable government, the German president capitulated and appointed Hitler chancellor.

But we don’t have to resort to that example. Did you know that France used to have PR? After World War II, the French Fourth Republic was established, and it used PR to elect its general assembly. Political scientist Michael Haas argues that the Fourth Republic was “immobilist.” The PR system allowed so many different factions to be represented that it became impossible for any of them to form a stable government. The French government proved less and less able to get anything done, as its problems grew increasingly severe. The collapse of the French colonial empire shredded confidence in the system. This eventually led to a coup. In 1958, French General Charles de Gaulle was encouraged by the President of France to seize power. His new constitution greatly strengthened the French president at the expense of the legislature. It was deemed at the time by many on the left to be an authoritarian power grab, and many French leftists still view the Fifth Republic as fundamentally undemocratic. Yet it is precisely because France tried PR that it ended up with this heavily presidential political system. The worse things get, the more dynamic democracy needs to be to adapt. But when things get bad, social divisions tend to intensify, and PR needs consensus to deliver new policy. The worse things get, the harder it is to produce consensus, and the harder it is to produce consensus, the less effective PR becomes at managing crisis. At the moment when you need the most out of democracy, PR is more likely to cause democratic institutions to collapse.

In recent years, the parties that have gained the most ground through PR have been on the right. In Germany, PR facilitated the development of the AfD. In the Netherlands, PR has aided multiple far-right parties. In Sweden, a far-right party now polls in third. This is occurring even though these countries have lower economic inequality and stronger public services than the United States. In America, economic stress is more severe, and cultural antagonisms are sharply developed. If the right can use PR to grow in European social democracies, there is at least as much reason to think it could use PR to grow in the United States. Then, PR’s tendency to obstruct change and produce prolonged stalemates increases the chance of dangerous constitutional crises. The right has a stronger presence in the armed forces than the left does. These are not situations we want to be in.

Avoiding Work Through Proceduralism

Despite all these problems with PR, you will still find many on the left who want to believe that electoral reform is the key. American leftists understandably look at our political system and see many obstacles. In the American system, new federal policy requires strong majorities in both the House and the Senate. It’s necessary to win pluralities in a majority of congressional districts and in a majority of states, and this requires very high levels of support in an incredibly diverse array of geographic contexts. Small, nascent parties and movements struggle to speak to so many diverse people and places. It’s hard to come up with enough money to fund competitive campaigns everywhere at once, and it’s hard to find a political message that can travel. Today, the American left is concentrated in the blue cities. Even in blue districts, we often lose primaries to centrist Democrats. The political strategies we use to compete in Democratic strongholds sometimes alienate us from voters in other parts of the country. Strategies that help us win some places make it harder to compete in other places. In this context, being able to get 15 percent or 25 percent of the seats just by changing the electoral law feels like a way out.

But this is a poisoned chalice. To win a few more seats now, we would permanently surrender any hope of transforming the country. In the European countries with PR, strong welfare states were installed with the help of American dollars in the years immediately following an enormously destructive World War. The Bretton Woods financial system supplied Europeans with American dollars, enabling Europe not merely to reconstruct its physical infrastructure, but to build the human infrastructure necessary to shore up their democracies in the face of authoritarian alternatives. Christian Democratic parties often cooperated with Social Democrats and Democratic Socialists to build these systems. None of the post-war conditions that allowed the continental European left to enact socialist reforms through PR obtain today, on either side of the Atlantic. The war is many years in the past. Richard Nixon abandoned Bretton Woods. The alliance between the Christian Democrats and the socialists is long shattered.

Even if it made sense, to enact PR would require a mass movement strong enough to force the Democrats and the Republicans to acquiesce to electoral reform. A 1967 federal law currently prohibits PR for congressional elections. We’d need to repeal that law, then either pass another federal law mandating PR or, if that proves impossible, push state governments to adopt it. It is just as difficult to do this as it is to push through the substantive social programs that directly improve people’s lives. In some ways, gaining support for electoral reform is harder, because promising voters access to housing, healthcare, or education is much more galvanizing than an obscure pledge to amend electoral procedures.

Ultimately the American left must do the hard work of finding a way to speak to the whole country. It will not be easy, but if we work at it, the right messaging and the right conditions may collide to deliver new economic rights sooner than we think. To do this, we must avoid the siren song of false shortcuts. We cannot just implement a set of procedural reforms and use them to skip past the hard constraints we face today. The desire to do this is understandable—the defeat of Bernie Sanders and the grim reality of the Biden presidency make any person with a heart want to crawl under a rock. But to surrender to this desire is to abandon politics for madness. We will never build working class support by indulging in a technocratic, elite discussion about changing the electoral system. Even if we were able to make these changes, they would not work. We must instead address the problems workers face in the here and the now.

EDIT: By reader request, this piece has been updated to include an endnote more precisely explaining the complex Australian electoral system.

NOTE: Australia is not a pure first-past-the-post system. The Prime Minister’s power rests on a majority in the House of Representatives. This house runs on a single-member winner-take-all system. It incorporates a “two-candidate-preferred” instant run-off element, but in practice the Australian House of Representatives is even more heavily dominated by its two leading parties than the British House of Commons. Currently 94% of the seats in the Australian House of Representatives are in the hands of Labour or the Liberal-National Coalition, while only 87% of seats in the British House of Commons belong to Labour or the Conservatives. The Australian Senate runs on proportional representation, but is considerably weaker than the House of Representatives—it can block legislation, but its powers to introduce legislation are heavily limited. It is somewhat stronger than the British House of Lords, but weaker than the US Senate. The fact that the Australian Senate runs on PR makes things harder for the Australian left rather than easier. The Australian Constitutional Crisis of 1975 was triggered when the Senate blocked legislation initiated by the Labour Party in the House. ↩