Asian American Psycho

Asian American fiction and film often function as lifestyle affirmation rather than explorations of the complexity of Asian American lives. The result is boring art.

Americans love Asian psychos. The angrier the characters, the bloodier the drama, the better. Consider some of the most popular imported cultural works from Asia in recent times. There’s the Oscar-winning Parasite, a film seething with class rage that climaxes with an orgy of violence at a child’s birthday party. Last fall, nobody could take their eyes off of Squid Game, a drama series that likewise explored social inequality in a literal death game where life and morals were cheap. Oldboy, a brutal story of obsessive vengeance, is one of the most revered Asian films in America (let’s pretend the American remake never happened), while The Vegetarian, an unsettling narrative of a Korean woman’s descent into madness, became a literary sensation several years ago upon its translation into English.

But take a look at the cultural works coming out of contemporary Asian America, and the picture is remarkably different. The mad, the bloodthirsty, and the depraved are replaced with the sad, the lovesick, and the eager-to-please. Asian psychos are great, so long as they remain in Asia. However, if Asians make the journey across the Pacific to become Asian Americans, we must repress any such disturbing complexity. The lord of a manor, once wicked and unrestrained in his domain, becomes the agreeable and obsequious guest. That mentality has a degenerative effect on our creative expression, trapping us in an adolescent mindset that’s too afraid to explore the darker sides of our humanity that make for the most intriguing art. Consequently, Asian American culture becomes stuck in a feedback loop, emotionally and developmentally stunted.

This timidity is especially rife in supposedly race-conscious contemporary Asian American literature. Many authors write with just enough racial awareness to flatter their readers into thinking they’ve read something bold and insightful, all the while avoiding any exploration of truths that would make both author and reader uncomfortable. It’s literature as lifestyle affirmation art.

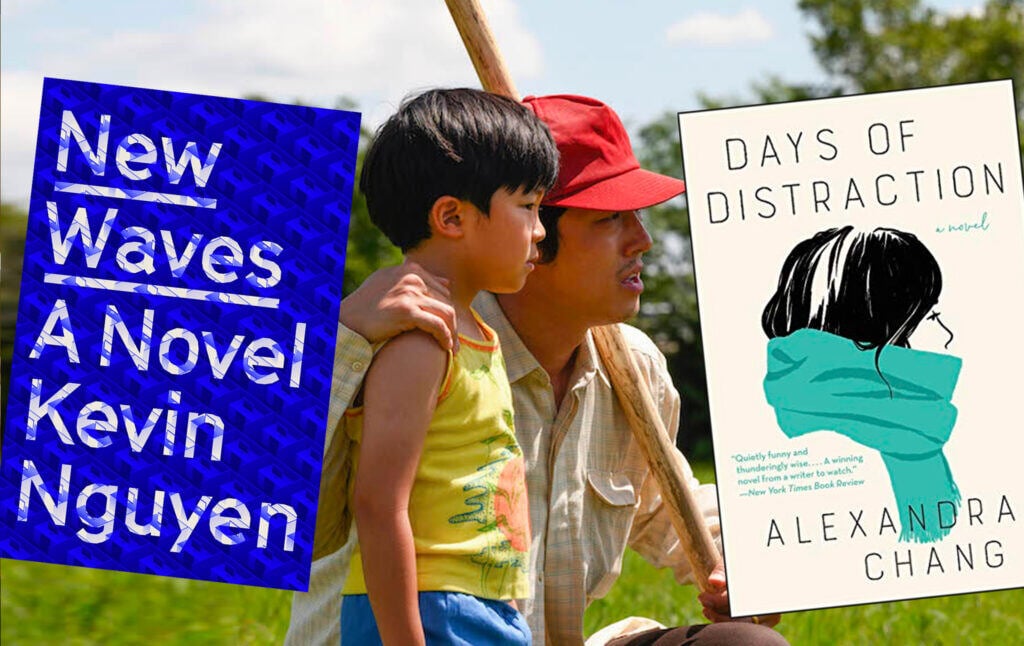

Two prime examples can be seen in New Waves by Kevin Nguyen and Days of Distraction by Alexandra Chang, both of which were published in 2020. The novels share many elements: 20-something Asian American protagonists who work in or around tech, a consciousness of modern Asian American racial identity and grievances, and a slice-of-life mode of storytelling. However, the books do differ in the genders of their protagonist, with Nguyen and Chang’s protagonists matching the gender of their authors.

New Waves has the veneer of a thriller-type story involving data theft, but at its heart, it is a more grounded narrative of how its protagonist Lucas deals with the sudden death of his best friend, Margo, a Black woman with whom he vents about race-related topics. Eschewing any pretense of a high-concept plot, Days of Distraction is about its protagonist Alexandra’s decision to uproot herself from San Francisco to follow her boyfriend J (his full name is never given) across the country upon his graduate school acceptance. This allows her to extensively ruminate about the racial underpinnings of her relationship with her white boyfriend, and why she and so many other Asian American women choose to be in such pairings.

Both novels received stellar reviews, making lists such as the Vanity Fair Best Books of 2020 List. Nguyen received praise from noteworthy novelists like Viet Thanh Nguyen and Celeste Ng, and George Saunders named Chang as one of her generation’s most important writers, a distinction reinforced by her recent selection as a National Book Foundation “5 Under 35” honoree. Given the plaudits these books have received and the subject matter they touch upon, they ought to provide some of the most insightful and fresh racial takes on young Asian American life. New Waves was even published under Penguin Random House’s One World imprint, which bills itself as racially groundbreaking and publishes writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates and Ibram X. Kendi. Yet despite the centrality of race in these novels—and the first-person perspective that ought to give readers a glimpse into the fascinating unspoken thoughts of young Asian Americans—nothing exciting or shocking is explored.

In New Waves, Lucas is an overweight and underemployed Asian American man in his mid-20s who works a low-paying customer service job at a tech company. He is not racially oblivious, and one of the first scenes in the novel shows Lucas griping with Margo about all the racism they have to endure in the workplace. This anger is supposed to be so intense that it drives them to steal their company’s data. But these grievances never go further than the type of Twitter bluecheck-approved complaints one would see on social media, such as how white people assume Black people like hip-hop or how Asians get ignored in workplace meetings. With such meager fuel, it’s no wonder the corporate thievery revenge plotline is extinguished after Margo is suddenly killed in an accident early in the novel.

Lucas’ racism radar continues to only go off at the safest of offenses, such as when he notices an ethnic fast-casual restaurant (cultural appropriation!) or when his starving-writer white girlfriend—whom he meets after hacking into Margo’s laptop after her death—applies for a housing lottery presumably meant for low-income minorities (gentrification!). Frustratingly, Lucas refuses to offer the reader any insights into underexplored racial matters that he’s uniquely qualified to testify on: what it’s like to be a broke unattractive Asian guy in a world that often laughs even at rich handsome Asian guys. When Margo is infuriated by yet another article about the dating difficulties of Black women and Asian men, he shies away, not even offering anything in his internal monologue to the reader.

“There’s nothing new in that article,” I offered, trying to find her some closure so we could both move on and talk about literally anything else.

“You don’t even do online dating. You don’t even date. What’s the big deal?”

“I don’t want a boyfriend. I don’t want a house. I don’t want a family, not that anyone is asking. I don’t want this job, but I also don’t know what better job there would be. I don’t want to live in New York, but I’ll never leave. My entire life is just things I don’t want,” she said. “It’s exhausting.”

“I feel like you’re mad I am not angrier about this article.”

“No, I want you to get why I’m so mad.”

It’s not just racism in dating that Lucas bovinely accepts. When he faces racial abuse on the subway, it’s his white girlfriend Jill who has to stand up for him. Again, all he does is shrug his shoulders.

“Jill, come on, it’s not worth it.” I pulled her back.

“Yeah Jill, come on, it’s not worth it,” the man said, kicking his voice up an octave. “Listen to your chink before you make him more upset.”

“I’m technically more of a gook,” I said, figuring I could end this before it turned into a confrontation.

Like Margo, Jill is baffled by Lucas’ placidity and even becomes angry at him for it. In another instance, Lucas again tries to make light of being called a gook by telling himself he’s impressed that a racist old white man had correctly identified his Vietnamese heritage. Is this supposed to be critical commentary on the debased state of the modern Asian American man as someone who can’t even stand up for himself? It is indeed believable that outwardly, a guy like Lucas would want to present an unflappable front as a coping mechanism. But it’s less believable that in the privacy of his own mind, he would feel absolutely no anger at being the low man on the dating totem pole, or at the ease with which people hurl racial insults at him in public.

Cowardly dullards who are terrified of even thinking an aggressive thought do exist. But even cowardly dullards can be riveting characters if written honestly. For example, Mr. Stevens from The Remains of the Day, Kazuo Ishiguro’s Booker Prize-winning novel about an old English butler who reflects on his life of impeccable service, is a captivatingly tragic figure precisely because of his repressed feelings for Miss Kenton and his delusions about his Nazi-sympathizing employer, Lord Darlington. All that Mr. Stevens refuses to say or acknowledge becomes subtext as to what kind of a man he is. Lucas, however, lacks such honesty as a character because he is more of a fantasy device that allows his author to gesture at identity consciousness, but from a safe distance. By doing so, Nguyen excuses himself from having to craft a more realistic Lucas, replete with all the embarrassing elements of Asian American male bitterness. Masculine rage is out of fashion at this moment, so it’s easy to see why Nguyen didn’t go down that particular road. But he has written a novel ostensibly about straight second-generation Asian American male identity, a demographic not commonly seen in contemporary Asian American literature. One can’t help but wonder if Nguyen—who is of the same tribe as Lucas, including having once worked in a low-paying job in the tech industry—is trapped by the limits of contemporary literary fiction and its tendency to veer into autofiction. In a Bookforum review of Philip Roth: The Biography, Christian Lorentzen wrote:

Authorial image management now seeps into the writing of fiction itself. The more readers (and critics) are content to conflate alter egos with authors, the more authors are tempted to idealize their fictional selves: confessional literature cedes the field to the autofiction of self-flattery.

Lucas’ absence of rage is precisely that self-flattery, for both the author and his demographic. Lucas may have a lot working against him in this society, but fear not, readers: he will not rise to anger. And for that, he will be narratively rewarded by having little trouble finding a girlfriend, and a white girlfriend at that. And even when they break up, she will compliment him on how dynamite he is in bed and what a good guy he is:

“Fine, I’ll start,” Jill said. “I was sad and you were sad and we could do that together, and you turned out to be a surprisingly good lay.”

“Why surprising? Because you assume…?”

She cut me off. “Because you are strangely considerate for a twentysomething who drinks too much and doesn’t know anything about the world,” Jill said. “And I really, really hate that I know you well enough that you were going to imply I was being racist.”

“You assumed correct.”

“Lucas, you need to stop blaming everything on how shitty other people are.”

“That’s easy for a white person to say.”

A reader should naturally wonder: does Lucas seek out white women to date as a way to thumb his nose at stereotypes of Asian male undesirability? Lucas also almost has a fling with an attractive Indian woman at his company while he’s in a relationship with Jill. Is he a sex addict or rampant cheater because of a racial chip on his shoulder? Is his lack of Asian female love interests, or even friends, a deliberate decision, perhaps a vengeful way to get back at the Asian American women who refuse to date Asian men? If these answers are yes, then that would make him a less presentable character, but an infinitely more fascinating and honest one at that. It’s just too bad the author of this type of literature has no interest in doing that.

At least Days of Distraction directly addresses the topic that New Waves only dares to tiptoe around. It’s a topic that is at the root of so many online Asian American political, social, and cultural discussions: the disproportionate prevalence of white-man-Asian-woman couples. Often derided as fuckability politics, it has been the singular obsession of both its critics and its defenders alike. It’s only natural that such a topic would be an all-encompassing issue in a minority population that has: (1) lacked identitarian confidence and viewed assimilation as aspirational, and (2) long been subjected to the gendered racism of hyperfeminization of both women and men.

Alexandra shares this obsession as she is unable to stop thinking about this racial couple combination. She even seeks out porn featuring Asian women and white men (but only if they act like a real couple). Living in San Francisco, Alexandra finds the sight of white men with Asian women all too frequent for her liking, making her wonder if there’s something “sinister” about how common the pairing is and whether her own relationship is somehow tainted in the eyes of others. She even voices this concern to her boyfriend:

“I’m not bothered,” I say. “I’m just thinking about it right now and I’m explaining to you what I’m thinking and how I feel. There are so many Asian-woman-white-man couples, and it’s like, why? Are all of the white men fetishizing the Asian women? Or are Asian women more prone to dating white men, and why? Or something else? Why don’t we ever find ourselves in a place with all Asian-man-white-woman couples? Or Asian woman-black-man couples? Or black-woman-white-man couples? Or Latina-woman-Asian man couples? Or—”

“Maybe you just notice them because you’re Asian and I’m white,” he says. “Maybe they just love each other and race doesn’t have anything to do with it.”

I burst out with fake laughter. “Yeah, right. Sure.”

This concern is especially vexing for Alexandra. She and her best friend Jasmine (who’s also an Asian American woman) frequently bond over how infuriating and racist white men are as their boyfriends, bosses, and employees. Yet separating themselves from such men, especially on a personal level, is never entertained as an option. Laughter is often the only way to deal with these uncomfortable realizations, such as when Alexandra expresses her insecurities to her sister:

Why are we with white men? Is it because we’ve been taught all of these years from all of this white American media that whiteness is the epitome of attractiveness? And even though we are aware of it, have we internalized it so deeply that it can’t be rooted out? (That might have something to do with it.) Or are we subconsciously trying to climb social and political ladders? Are we fitting into this stereotype of the gold-digging Dragon Lady Asian wife? (We hope not!) Or was it that, where we grew up and went to school, white people were more readily available? (Must play a role.) Or, my sister muses, are we trying to ensure that our kids are part white? (I am probably not having kids, I say. Okay, she says.)

“I’ve thought about that a lot lately—am I dating a white guy to make sure that my future kids are also white, and have it easier? Is that a form of survival?”

“Well, are you?”

“I don’t think so? But I don’t know! Maybe it’s subconscious!” We laugh for a while. It is funny. It’s all too funny. We survive through the laughter.

To Alexandra’s credit, she’s willing to voice these uncomfortable thoughts aloud to others, even acknowledging that being with a white man confers the privilege of half-white children (a notion that may get her tarred and feathered in some Asian American social justice circles). She cites all sorts of information from OKCupid, Pew, historical anti-miscegenation documents, and sociological studies on race and desirability. She extensively reads the accounts of Yamei Kin and Pardee Lowe, two Asian Americans from the turn of the 20th century who married white partners. She references posts from Reddit by angry Asian American men, and even expresses some sympathy for them. That’s all quite informative, but a novel is not a research paper. A novel, particularly one from the main character’s perspective, presents an opportunity to diverge from facts and enter tantalizing subjectivity. No other medium allows for this to such a degree, yet Alexandra does little more than recite facts and express standard-issue liberal guilt. If one suspects Nguyen of holding back in New Waves because of his identification with Lucas, then it must go doubly so for Chang who has outright stated how autobiographical her novel is.

Alexandra would be far more memorably intriguing if she were ruthlessly honest, even if only in thought. What if she expressed utter disdain for those angry Asian men on Reddit? And even toward the Asian men who are good to her, what if she ultimately saw them as beneath her, as barriers on a specific type of well-trod path to a higher stratum of society that’s available to her as a straight Asian American woman? Unlike Lucas, Alexandra is repeatedly told that she is beautiful and in high school, she had been eventually included in the popular white girls’ clique. Their life experiences are worlds apart. What if, in another hypothetical scenario, a ruthlessly honest Alexandra met a ruthlessly honest Lucas? What would she think of him, and vice versa? That would’ve been the groundwork for an engrossing story.

But, as befitting posh liberalism, proper observation of manners and recognition of one’s own privilege are of utmost importance as they’re the pathway to atonement for whatever guilt you have about your own blessed lifestyle. Having properly confessed all her anxieties, Alexandra is absolved by her best friend Jasmine, who tells her that she and J are not like those bad white-man-Asian-woman couples because she’s been with him since college and that they’re the best and sweetest couple ever. Jasmine would appear to be correct since throughout the novel, Alexandra describes J as an excellent boyfriend: he is “beautiful,” “lithe,” listens to all her racial neuroses, and gets along with her family. Jasmine also states that there are simply more white men around than any other race of men in America, so case closed. She concludes by saying:

“No! I mean, to be honest, I’m still staying away from white guys. But that’s me and my bad experiences. Hashtag boundaries. Hashtag self-care! But I’m staying away from psycho misogynists, too, whatever race. Only enlightened men for me. Which means maybe I’ll be single forever!”

I laugh. Already I feel better.

Toward the end of the novel, when Alexandra travels to China in order to get away from J for a while, both her parents assure her that he is a good man and boyfriend, thus paving the way for a mini-reconciliation after a mini-crisis. All’s well that ends well. As Jasmine says, it’s all about self-care. And that may be the ideal choice to make in one’s personal life: to choose happiness over some quixotic moral crusade to defy societal peer pressures that, in the end, will help no one and only hurt you. But this is a novel, where anything should be possible, including exploration into the dark and depraved. It’s what the safety of fiction and artistic expression is supposed to give us.

Instead, what is produced is little more than a coddling of both the artists and audience. Neither Nguyen nor Chang is willing to impugn themselves or their demographics with any harsh truths. The function of the Lucas character is to offer a racial CAT scan of the straight second-generation Asian American man’s brain and find that there’s nothing to worry about, that even the biggest losers among us—with no money, no looks, and no respect—will never get mad. We might not even acknowledge we have problems of feeling alienated and unwanted! And for that good behavior, the novel implies that we’ll stumble into multiple romances with non-Asian women. In contrast, the Alexandra character is portrayed more as an intellectual hypochondriac, needlessly fretting over something that she shouldn’t feel bad about. The thrust of the narrative is less focused on true introspection and more on validation of the life choices of the author’s demographic, to flatter such an audience that no matter what queasy racial implications are involved in their romances with white men, they deserve to live laugh love without inconveniences.

If there seems to be hyperfocus on interpersonal relationships in contemporary Asian American cultural works, it reflects the priorities of the established Asian American culture class. With so many writers, filmmakers, and other artists coming from well-to-do upbringings (I too come from this background) or aspiring to its values, their primary racial conflicts involve assimilation anxieties at a personal level. Themes of not feeling pretty/handsome/cool enough pervade a lot of these works. Such sources of angst, even if they appear to be the unresolved childhood issues of mundane two-parent middle-class households, are not automatically worthless. There is no problem that’s too small to be the genesis of a great narrative. The status quo’s artistic misdeeds are not necessarily because of the happy accident of the artists’ personal histories, but rather, because the artists have allowed themselves to be limited by these histories. Assimilation into a white liberal metropolitan culture is treated as inevitable. The process may be bittersweet, confusing, and maddening, but it is a foregone conclusion. And since that is the path chosen by the exclusive club of contemporary Asian Americans artists, it cannot be questioned.

The result is lifestyle affirmation and ego-protection for everyone involved: the authors and their demographics are ultimately good people, and their readers are enlightened progressives for learning about authentic minority experiences. The grand problem in all this is not necessarily whether certain life decisions were correct. Rather, it’s how the writers have devoted their creative drive to the mission of justifying those decisions. All this makes for terrible art. Or worse, boring art.

There are some rare exceptions to this rule of sedated Asian American cultural works. In Private Citizens by Tony Tulathimutte, one of the main characters is Will, a wretchedly insecure young Asian American man who clings to his white girlfriend for status and also does things like digitally alter his vast porn collection to feature more Asian men. Free Food For Millionaires by Min Jin Lee is about a flawed and often unlikable Asian American woman, Casey, using all the tools at her disposal to rise from her Queens roots to the top of the white-collar world in 1990s Manhattan. Despite its reputation as a breezy wealth-porn type of novel, Crazy Rich Asians has a razor-sharp scene that bluntly discusses why the protagonist, Rachel Chu, was loath to date Asian men until she met the Singaporean Prince Charming in the story (this scene was, of course, eliminated in the movie for sensitivity reasons). And the film Better Luck Tomorrow depicts a group of studious and ambitious Asian American high schoolers’ slide into crime and murder.

There are also some notable attempts that don’t quite work. White Ivy by Susie Yang has a great premise about a relentlessly social-climbing Asian American woman, Ivy, who is determined to marry into a Kennedy-like clan at any cost. Unfortunately, the novel holds back on truly examining the anti-heroine’s mind. For example, when Ivy’s family sets her up with a dorky fobby Asian man, she is irritated, but we never see just how full of contempt she would be towards a man like that, even though she’s supposed to be a sociopath. And Celeste Ng’s Everything I Never Told You delves into the crippling effects that Asian American self-loathing can have in a marriage with a white partner. In the novel, however, Ng writes the self-hating Asian character as the husband instead of the wife, even though significantly more Asian American women are married to white spouses than Asian American men are. The switching of race and gender is a curious decision in the genre of literary fiction, a genre that’s often guilty of solipsism and being little more than thinly disguised memoirs. Charles Yu won the National Book Award in 2020 for Interior Chinatown, which explores the troubles of contemporary young Asian American men. However, it’s still politely well-restrained, culminating in the protagonist’s impassioned tirade where he still acknowledges his straight Asian male privilege.

But these types of works are the exception, not the rule. Better Luck Tomorrow is well-honored in Asian American circles, but nothing has truly followed in its footsteps. Instead, we get things like Crazy Rich Asians, The Farewell, Always Be My Maybe, To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before, The Half of It, Tigertail, Minari, and Shang-Chi, all of which serve to make us Asian Americans feel better about ourselves, either through aspirational fantasies or crying sessions. It’s not that I want Crazy Rich Asians (which I enjoyed watching) to be like a Na Hong-jin movie. But will there ever be an Asian American equivalent of The Chaser and all its brutality and bleakness?

Whereas America wants Asian American works to be toothless and pacified, it thirsts for the exact opposite from Asian ones. It’s not that Asia doesn’t create its own share of quietly introspective or life-affirming works; it’s more that Asian America can’t create anything except that. The pressure comes both externally and internally because the fear is not that Asian American anger is irrational, but rather, such anger would be all too rational. And if such justified discontent were to be voiced by our cultural representatives, then the societal consequences could be immense. America’s racial self-esteem would plummet if Asian Americans could no longer be propped up as shining examples of its racial generosity. Asian Americans may lose our place as junior partners in the progressive diversity coalition if we demand too much attention for ourselves, especially on divisive issues like school testing and physical safety if we advocate for standardized testing and for stricter measures in the criminal justice system. And if Asian Americans become too much of a problem, then nobody will stand with us as Yellow Peril ideology returns full force with the rise of China.

Thus, Asian Americans must be eternally happy or contently resigned or heartbrokenly wistful. What we can never be is angry. Asians in Asia can be as psycho and insurrectionist as they want, though. If there is turmoil in those faraway societies, it would be quite the spectacle of Oriental madness, like those wacky samurai and their seppuku rituals.

Just look at how differently the financially desperate Asian characters of Parasite and Squid Game act when compared to their counterparts in Minari. In Parasite, Kim Ki-taek (played by Song Kang-ho) finds himself and his family in a humiliating position in society. They have to freeload off of others’ wifi and they fold pizza boxes to try to make ends meet, only to get berated by a teenage superior for not being fast enough. Their children’s educations have been halted, eliminating any chance of the next generation climbing out of the figurative and literal basement of Korean society. To fix this, his son hatches a scheme to ingratiate themselves as employees of the wealthy Park family. Every single member of the family engages in underhanded ploys, from lying about credentials to getting competitors fired. Ultimately, Ki-taek proves willing to commit murder to assuage his wounded pride and take revenge on a society that has disdained him for too long.

In Squid Game, very few of the characters are heroic role models. Even the protagonist Seong Gi-hun (played by Lee Jung-jae) is a deadbeat dad who prefers gambling to responsible fatherhood. Well into middle age, he lives with his mother and is a financial burden to her. He is constantly disappointing his daughter, to the point where his ex-wife has no qualms about taking her away permanently to America. When Gi-hun finds out about this, his solution is to participate in a contest where he is expected to be indifferent to others’ deaths, inflict such deaths himself, and betray friends’ trusts. Other characters in dire straits—Cho Sang-woo the financier, Han Mi-nyeo the con-woman, and Jang Deok-su the gangster—have no reservations about doing whatever is needed to survive, and the show’s unsparing depiction of what people are capable of in such difficult circumstances was one factor that made the show so compelling, especially in today’s heavily moralistic American pop cultural landscape. And the few genuinely good-hearted characters, like Ali and Ji-yeong? All mercilessly killed off.

But shift the stage to Asian America, and it’s hard to imagine the farmer dad in Minari, Jacob Yi (played by Steven Yeun), behaving so depravedly, though his situation as a heavily indebted Korean immigrant farmer in America is not much better than that of Kim Ki-taek or Seong Gi-hun. After a decade of, as he puts it, “looking at chicken assholes” for a living, he achieves a piece of his dream of owning a farm. But it’s in rural Arkansas, in a mobile home in a tornado alley, with few potential friends around except for a kooky religious neighbor. One bad harvest could wipe him out, his water supply is unreliable, his wife is losing faith in him, his only nearby community is an all-white church, and a grocer screws him over by reneging on their agreement. And in the climactic ending, with his marriage on the rocks, his mother-in-law accidentally burns his entire crop down, just when he has finally closed a deal to supply a grocer. Furthermore, there are implications that he has a selfish delusion of grandeur, of putting his desire to become an independent farmer above the welfare of his family. All the elements of a psychological meltdown are there.

But instead, his story is that of quiet fortitude and dignity. The calamitous fire turns out to be a blessing in disguise that teaches the Yi family the most important thing in life: that they have each other. This is not to say Minari is a bad film. It is well-made and moving. Lee Isaac Chung had a specific, heavily autobiographical story he wanted to tell and he has no obligation to be someone he’s not. But why must almost every Asian American narrative be like this? Why is there never any fury, any degeneracy, any insanity? Why’s it always ceaseless melancholy, in both art and real life? In a panel hosted by Sandra Oh, there was a teary conversation between the Asian American moderator and cast as they reflected on the pain and difficulties they’d faced as second-generation Asian Americans. The Korean cast was a bit confused by this, as they had no personal experience with such Asian American matters. Maybe Youn Yuh-jung, who won an Oscar for her role as the grandmother, was also wondering why Steven Yeun’s character didn’t go psycho in the end.

Asian American pain rooted in the children-of-immigrants experience is real and worthy of respect, but there comes a point when only expressing that pain through sadness or self-censorship becomes detrimental to artistic possibilities. The problem with Minari is not that it’s gentle and tender; it’s that we rarely see anything different from Asian American art. The Farewell, a film in which a young Asian American woman and her family must go to China to say goodbye to their terminally ill grandmother who has been purposefully kept ignorant about her own diagnosis, was another well-received and well-made Asian American film, and it too dwelled on the aching wistfulness of the second-generation experience. What are the chances of an Asian American supernatural revenge fantasy novel or movie being made about Yang Song, where she becomes resurrected to take revenge on the NYPD officers who abused and raped her? How can Asian Americans ever hope to effectively critique a society if we’re so desperate for acceptance and love from it, to the point where we displace all our legitimate anger into the impotent, almost adorable, rage against office microaggressions and white people making dumplings? What does an Asian American pushed beyond his or her brink by American society look like? Most people right now, including Asian Americans, do not want to know. But great art should make us push past such inhibitions.

There will be much resistance to dangerous and angry Asian American art. From within, there will be many who still need our creative works to function as feel-good therapy for racial melancholia and self-loathing. From the outside, there will be discomfort—even fury—at Asian Americans refusing to be the good boys and good girls of American race relations, the one true success story that Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty can be proud of. But the purpose of Asian Americans is not to make other groups feel better about themselves, to spice up their palate, to make their lives less lonely. Asian Americans have a purpose of our own. To many second-generation Asian Americans, Asian America is all we have. Feeling neither Asian nor American may be a trite sentiment, but it isn’t false. The only thing we can truly be is Asian American. A genuine Asian American culture cannot be a simulacrum of its Asian or American counterparts. Asian Americans must delve deeper and more critically into our own unique experiences. A culture is nothing without a rich artistic tradition. Whether art and culture precipitate change or reflect the status quo is a common debate. Either way, the debased state of Asian America is exposed in our cowardly and juvenile art, and only by being more truthful and less image-conscious in our creative self-expression will we finally mature as a culture. Otherwise, we will remain a lost generation that has resigned itself to insignificance, a transitory and ephemeral nation between the pathetic journey from Asian to American.