Borat As Milgram Experiment

The film’s lesson is not so much that Americans are bigoted, but that they decline to take moral stands when it counts. The implications should disturb us all.

I truly did not believe the world was in need of a second Borat film, but after prodding from friends and colleagues, I watched Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan. I am glad I did, because 1) it was funny and 2) I have become convinced that the film offers a useful parable about the “banality of evil” and the moral necessity of active resistance to injustice.

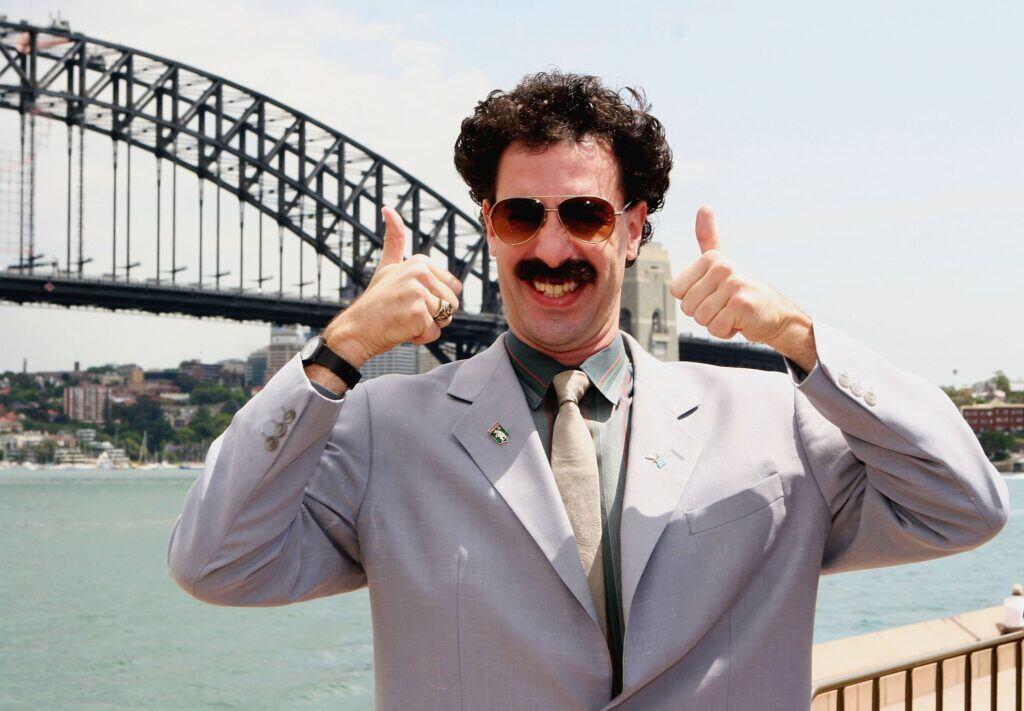

Sacha Baron Cohen once again plays goofy “journalist” Borat Sagdiyev, who is back in the United States, this time ostensibly sent by the Kazakh government to deliver a live monkey to Vice President Mike Pence. When the monkey is accidentally killed, Borat instead decides to deliver his 15-year-old daughter, Tutar, as a gift to the VP (Pence is described as a “pussy hound” so voracious that he cannot trust himself to be left alone with a woman).

The premise of the film is mostly beside the point. As with the first Borat, the new film is mostly an excuse to play amusing pranks on unsuspecting Americans, and expose some of the ugliness and absurdity of this country. In a famous earlier Borat skit, the character got a honky tonk bar to sing along to a horrifying anti-Semitic country song. This time, he gets a crowd of Trump supporters to sing a song about wanting to inject Anthony Fauci with the “Wuhan flu” and chop up journalists “like the Saudis do.” In many Borat setups, Baron Cohen’s character will say something deeply misogynistic/anti-Semitic/criminal and see how the everyday Americans he is pranking will react. For instance, with his 15-year-old “daughter” present, he tells the owner of a farm implement store of his need to keep her in a cage, and ask for recommendations on appropriate cages. To a plastic surgeon, he will describe the need for his daughter to have a less Jewish-looking nose, and the surgeon will agree that this is desirable. (Incidentally, Bulgarian actress Marina Bakalova completely steals the show as Borat’s daughter and deserves an Academy Award.)

Baron Cohen is sometimes described as “exposing the prejudices” of Americans with the Borat pranks. But this is not quite what is usually going on. Typically, Borat says something horrifying and bigoted, and the Americans nod and smile and go along with it. For instance, in a bakery, he asks for a cake that says “Jews will not replace us 🙂 🙂 :)” and the affable baker dutifully writes the message out in blue frosting.

Does this expose the baker’s prejudices? It’s better described as exposing the baker’s moral cowardice, the lack of willingness to challenge someone else’s prejudices. I don’t think the crowd who sang “Throw The Jew Down The Well” were necessarily thinking many dark thoughts about Jews, though some of them appear quite gleeful. Nor do I even think all of the crowd who sang about chopping up Dr. Fauci necessarily dreamed of doing it—though the one heiling certainly seemed menacing. Instead, I think they just didn’t really think about the implications of what they were saying or doing. This does not mean they are not also bigoted, in part because bigotry is the failure to think about the lives of other groups the way you think about your own. The reason one can be racist without “hating” anyone is that one can be racist simply by assigning more consideration to people of your own race than people of other races.

What Borat really exposes, more than anything, is how the fear of awkwardness prevents many people from wanting to step out of line and point out the wrongness of something. If the other person in an encounter confidently presents a particular thought as normal, and does not appear to expect any contradiction, it takes courage to step up and create a “scene” rather than simply going along with things. The man selling cages just thought of himself as a man selling cages. It is not his job to ask what the cages are used for. Baron Cohen tries to demonstrate the extremes to which this can take people; he goes so far as to ask for recommendations on how to successfully gas “g*psies,” and is given thoughtful advice on the technical aspects of the problem. Even if the cage-seller does not feel “hate,” he certainly doesn’t feel any automatic revulsion at bigotry or genocide, and has a mental hierarchy of moral worth in which members of some groups are cared about more than others.

In the new film, Baron Cohen mostly targets Trump supporters, from the rally attendees to Rudy Guiliani to a meeting of Republican women to a pair of gun-toting QAnon bozos. Importantly, few of them seem actively malevolent. They are not angry, hateful fascists for the most part—in fact, most seem rather harmless. They are usually quite nice to Borat, and try their best to accommodate him and not rock the boat.

But they are not harmless, because being affable does not mean being good. The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing. The most disturbing takeaway from Borat is that Americans, while perfectly “nice” and unfailingly polite, do not have what it takes to be moral people. Moral people do not politely help someone figure out ways to commit genocide. Moral people are often not polite, because they understand that it is necessary to puncture the bubble of civility, to cause some discomfort, in order to tell the truth.

One of the Americans appearing in Borat does do this. Jeanise Jones, a Black woman who babysits Borat’s daughter, is horrified by what she encounters. Bakalova as “Tutar” tells Jones that she is being groomed to be given to an older man, and recounts all kinds of sexist beliefs about the limited capacities of women. Jones was genuinely disturbed, and in the film she encourages “Tutar” to challenge her father and break free of her internalized misogyny. Jones confronts “Borat” and tells him exactly what she thought of his despicable attitudes, the only person in the film to do so bluntly.

For every Jones, there are dozens of people who will simply go along with almost any amount of injustice to avoid making a fuss. This is the central finding of the Milgram experiment, which showed that ordinary people would be willing to commit terrible acts of harm if they were directed to do so and were uncomfortable with speaking up about their reservations. Importantly, the Milgram experiment also showed that those reservations were quite real, and that when one person “breaks the silence” and calls out an injustice as an injustice (in the case of the experiment, refusing to deliver an electric shock to someone), others will “find their voice” and follow suit. In other words, while it is true that “good men doing nothing” is an enabler of evil, it is also true that even a few good people doing something will create a “domino effect.” If, for example, a store customer had told Borat that it was insane to want to gas and cage people, the store proprietor would almost certainly have spoken up and not gone through with the sale.

It is unclear how much of the Borat films is “real,” since Baron Cohen freely mixes staged segments and live pranks and it’s not always obvious where one ends and the other begins. The number of pissed-off participants to emerge after Borats 1 and 2, though, suggests it is a good deal “realer” than we might hope. It is clearly not a “scientific” experiment, of course. But even understood as a work of fiction, the moral lesson about America is the same.

This lesson is easy to miss. On the “dumbest” level, one can watch Borat as making fun of Eastern Europeans, and from the number of people who came away from the 2006 film repeating the catchphrases “Very nice” and “My wife,” I do think there are some who saw the butt of the joke as Kazakhstan rather than America. A slightly more sophisticated analysis sees Borat as an expose of the many kinds of racist, sexist Republicans who populate Middle America. But, while I am no fan of Republicans, I think that view allows liberal viewers to let themselves off the hook, by seeing those other Americans—the ones with the backward views—as the ones being lampooned.

Properly understood, I think Borat is a very deep indictment of all of us, because the tendencies it shows in the QAnon dudes are not limited to QAnon dudes. The tendency that is most omnipresent among the film’s unwitting subjects—declining to do or say anything when the facts of an injustice demand it—is just as present among enlightened liberals. The target of the film is not prejudice but passivity; knowing that something is wrong but lacking the guts to step forward and do the right thing.

Sometimes the passivity in the film has nothing to do with “injustice.” Borat and Tutar attend a debutante ball in Georgia and perform a disgusting dance involving copious amounts of menstrual blood, and the attendees simply look on with increasingly pained expressions, their decorum-addled brains having no idea what the proper response is to such a situation. They have been trained to act according to precise sets of rules, so when something flagrantly violates the rules, they do not know how to adapt themselves. Having shed their free will, they simply stand there malfunctioning. Does not compute.

When Donald Trump crashed through all of the norms of politics, shattering them one by one and suffering no consequences, plenty of people were dumbfounded. “But he… can’t do that,” they seemed to think. He could, though, and he did. For years, many of us have been somewhat paralyzed, simply having no idea what part we should be acting now that the entire script has been thrown away. What do you do? How do we deal with this?

The problem is that doing nothing is not an option. Each of us has to learn to think hard about what is right and wrong and what is required of us in the circumstances in which we find ourselves. This is what the Americans in Borat failed to do. They followed narrow sets of algorithms—e.g., “the job of a hardware store clerk is to help the customer”—without noticing how that formula could produce perverse results in a situation where the hardware store clerk is faced with a situation necessitating a moral stand. We should have learned 75 years ago that “just doing my job” is not an excuse for evading self-scrutiny, but many Americans clearly haven’t yet learned to do the hard (and awkward) work of thinking and speaking for themselves.

I don’t exempt myself from the indictment. I know why the people in the Borat film didn’t say anything. I don’t know that I would have said anything. I hate confrontation. I like to be polite and nice. I don’t want to be rude. Would I take that so far as to not even tell someone that keeping their daughter in a cage is abominable? No, I’d probably speak up about that. But I know I’ve failed in other situations. I’ve watched people be arrested for obviously bullshit reasons and I have shuffled away awkwardly, too cowardly to confront the police. If I heard ICE show up to take away a neighbor, or a bailiff show up to start an eviction, would I be able to run out and confront them? What would I do if I saw someone hit a child in front of me? What about if I saw an employer mistreat a worker? It can be hard sometimes to know what your obligations even are, and harder still to carry them out. Much easier to slink away and pretend you saw nothing.

A lot of fuss is made about what is derisively known as “call-out culture,” which is seen as the tendency to too easily criticize people for perceived slights and injustices. I do think we need to be compassionate and forgiving and not to try to relish pointing out each other’s defects, but in some ways we need more of a “call-out culture,” in that too many horrible things pass by without ever being pointed out and condemned. The job of a humane person is not to be as nice as possible, but to notice and try to stop the cruelty that they see occurring around them. Until everyone does that, there is more “calling out” to be done.

Don’t get me wrong: Borat is in many ways dumb fun, and I am not saying that Sascha Baron Cohen is the Hannah Arendt of the Trump era. But beneath all the goofiness, the film contains important observations about the banality of evil. Climate change is not being exacerbated by malevolence as much as indifference; we do not notice or care what is being done, and are unwilling to call the villains what they are. Evil is banal; it looks normal and good and polite, and that is what makes it so insidious. The scariest thing about the “bad,” prejudiced people in Borat 2 is that they are normal. They do not notice what they are complicit in. And we should all realize, to our horror, that that could easily be us, too. Which injustices are we ourselves passing by without doing enough to call out and stop?