The Politics of Shame

How effective is shame as a tactic? Are there better responses to shameful behavior?

Donald Trump is a bad president.But that’s not why we loathe him.

Indifference to the environment, the human cost of a tattered social safety net, and the risks attendant to reckless nuclear threats are hardly unique aspects of Trump’s presidency: they’re the American way. It’s certainly alarming that Trump has repealed common-sense environmental regulations, threatened social services, and withdrawn from the Iran deal. But those acts, which would also feature in a hypothetical Ted Cruz presidency, don’t explain the scale of the reaction to Trump. They don’t account for the existence of neologisms like “Trumpocalypse,” or tell us why late-night hosts and satirists are constantly inventing new, creative ways to mock POTUS’s weave.

The feature that makes Trump unique, and the focus of a particular kind of outrage and contempt, is not his policy prescriptions or even his several hundred thousand character failings. God knows plenty of presidents have been horrible people. What sets Trump apart is his shamelessness.

For example, Trump is not the first president or popular public figure to be accused of sexual assault—it’s a crowded field these days. But he was the first to adopt a “takes one to know one” defense—using his political opponent’s husband’s accusers as a human shield to deflect personal responsibility.

Instead of following the prescribed political ritual for making amends after being caught in flagrante, namely, a contrite press conference featuring a stiff if loyal wife, Trump chose to go on the offensive, even insisting that the infamous “pussy tape” must have been a fabrication. Trump established the pattern of “doubling down” early on when he refused to walk back his comment that John McCain’s capture and subsequent torture during the Vietnam War disqualified him from being considered a war hero. It seems attempts to shame Trump only provoke more shameful acts which fail to faze him.

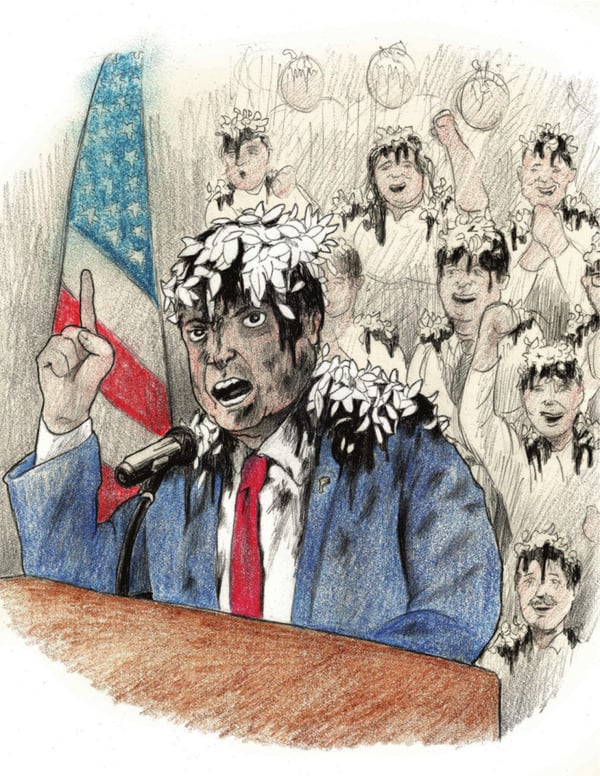

Where other presidents have been cagey, Trump is brazen. He did not invent the Southern Strategy, but he was the first to employ it with so little discretion that the term “dog whistling” now feels too subtle. (Remember, the tiki-marchers shouting “Jew[s] will not replace us” contained among them some “very fine people.”) There is no shortage of vain politicians, but while John Edwards felt compelled to apologize for his $400 haircut, Trump flaunts his saffron pompadour and matching face. Nepotism may be as old as the Borgias, but the boldness with which Trump has appointed family members and their agents to positions of authority still manages to stun. And while nuclear brinksmanship was a defining feature of 20th century presidencies, never before has the “leader of the free world” literally bragged about the size of his big red button and attempted to fat-shame the leader of a rival nuclear power.

Even when it appears as if Trump is on the verge of an apology or admission, he quickly lapses back into shamelessness. When Trump was criticized for lamenting violence on “many sides” following Heather Heyer’s murder in Charlottesville, Trump was pressured by advisers into releasing a statement explicitly condemning neo-Nazis. But he soon walked it back, once again blaming “both sides” and the “alt-left” for being “very violent.” (Again, remember which side featured a white supremacist who killed a woman.)

This impudence, this shamelessness, is essentially Trump’s calling card. And those who object to it have often sought to restore the balance by trying even harder to shame him, or, in the alternative, by trying to shame his followers into acting like reasonable human beings. “Shame on all of us for making Donald Trump a Thing,” wrote conservative writer Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry back in 2015. Throngs of protestors chanted “shame, shame, shame” along Trump’s motorcade route after his “fine people” remark. The Guardian’s Jessica Valenti wrote that shaming is both justified and “necessary” because “there are people right now who should be made to feel uncomfortable” because “what they have done is shameful.”

MSNBC host Joy Ann Reid has also sought to shame Trump voters, for example by tweeting: “Last November, 63 million of you voted to pretty much hand this country over to a few uber wealthy families and the religious far right. Well done.” Washington Monthly contributor David Atkins has echoed this sentiment, tweeting: “Good news white working class! Your taxes will go up, your Medicare will be cut and your kid’s student loans will be more expensive. But at least Don Jr can bring back elephant trunks on his tax deductible private jet, so it’s all good.”

“How could he/they!?” is a popular way to start sentences about either Trump or his supporters. The statistic that 53% of white women voted for Trump (how could they??) is a useful tool both for shaming others and the self-flagellation-cum-virtue-signaling characteristic of some white women who “knew better.” Even suggesting that politicians talk to Trump voters is grounds for ridicule. Forget scarlet letters—nothing short of community expulsion will do. They’re “irredeemable” after all. So why bother “reaching out”?

Believe me, I empathize. Trump’s policies hurt people, and the people who voted for him did so willingly. Given the easy-to-anticipate consequences of their votes, Trump voters do seem like bad people who should be ashamed. We’re often encouraged to engage more civilly with “people who disagree with us,” but the divergent value systems reflected by America’s two major political parties cut to the core of who we are. They are not necessarily mere disagreements, but deep moral schisms, which is why commentators like Valenti insist that a high level of outrage is appropriate to the circumstances. If you’re not outraged, you’re not taking seriously enough the harm done to the immigrant families torn apart by ICE. Mere fact-based criticisms of various policy positions feel inadequate, as if they trivialize the moral issues involved. It seems important to add that various beliefs, themselves, are shameful. No wonder, then, that the shared impulse isn’t just to disagree, but to “drag,” destroy, and decimate.

Given what’s at stake, I understand why shaming feels not only appropriate, but compulsory. It’s an inclination I share and sympathize with.

But in practice, I think it’s a mistake.

Why? As it turns out, social science confirms that shaming is an ineffective strategy for motivating moral behavior. According to a 2007 study by June Price Tangney, Jeff Stuewig, and Debra J. Mashek, shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride each function as emotional moral barometers that help individuals to assess and correct behavior. But unlike guilt, which is tied to specific acts of wrongdoing, shame provokes a holistic negative self-evaluation that impedes one’s ability to internalize and learn from bad behavior. While the person experiencing guilt thinks “what a terrible thing I did,” and then considers the effect their actions have had on others, the person experiencing shame thinks “what a horrible person I am,” and searches for a way to preserve their self-esteem. Guilt is adaptive: it causes us to isolate and rehabilitate a specific “bad” behavior. But shame is uniquely hard on the ego. The results can be disastrous.

Feeling their entire self-image under attack, shame-prone individuals are more likely to externalize blame and lash out destructively, including physically and verbally. According to the study, shamed individuals are prone to “turn the tables defensively” and direct their anger toward “a convenient scapegoat”—all in a bid to regain control and superiority in life. Moreover, where guilt evokes “other-oriented empathy” and is more likely to lead to behavioral change, shame disrupts the empathy process. Instead of considering ways to remedy our behavior, shame prompts us to become self-protective and defensive of our identities. Does any of this sound familiar?

Defensive grandiosity, anger, and violence all characterize the alt-right movement, and while I can’t definitively prove a connection, my instinct tells me that gloating over “white tears,” while cathartic, doesn’t exactly ease white Americans through the transition from white hegemony to racial equality. It is axiomatic that when you’re used to superiority, equality feels like oppression. The left can internalize that insight as a way to process and dismiss white angst, or it can be used to our strategic benefit. As we lurch toward greater equality, the relevant question is not whether certain white Trump voters have an outsized persecution complex (they do), but whether adding shame to the powder keg of white resentment is likely to have the redemptive qualities we imagine.

Current Affairs contributor and Alt-Right Aficionada Angela Nagle has extensively chronicled the relationship between sexual insecurity, misogyny, and white supremacy in online chat rooms. The pick-up artist community, which caters to men who underperform traditional masculinity, has been a gateway group for many members of the alt-right—many of whom are able to locate a sense of belonging and an alternative source of pride in racial separatist movements. Last August, in Charlottesville, we saw the potential for how violent their externalized anger could be.

Of course, the responsibility for bigotry lies squarely on the shoulders of bigots, but it’s worth considering whether the language we use might influence whether whites see the future as one to be afraid of, or as an inclusive one in which equality benefits them too. There are humanistic reasons for that: everyone, regardless of race, should be able to feel a sense of community belonging and individual pride in an egalitarian future. But it is also in the self-interest of racial justice movements to think about the social factors that help drive the discontented in one direction or another. If a particular method is found to actually fuel the growth of the alt-right, it needs to be examined critically, because nothing is more liable to hurt people of color than a flood of angry young men joining white supremacist groups. It may not be our “job” to assist white people’s adaptation to a new multicultural reality. But unless the political dynamics of backlash are carefully understood, important victories in the fight against racism may prove transient.

There’s an additional strategic angle to this critique of shaming: it often causes us to misattribute the motives of our political opponents. Focused on the ethical implications of conservative political positions, the left often makes the arguments that feel most virtuous rather than those which are the most persuasive and accurate.

For example, liberals interpreted the GOP’s support of senatorial candidate Roy Moore as evidence of Republicans’ moral depravity. Who, after all, could support a man who, at age thirty-four, sourced dates by scouring family court for the underage subjects of custody proceedings? As journalist Jonathan Cohn put it, “[t]he GOP supports sexually assaulting children and taking away their health insurance. They are cartoon villains.” But as justified as that criticism is—the Republican Party does show a callous indifference to both sexual violence and uninsured children—drawing the GOP as cartoon characters flattens and oversimplifies. Because it fails to acknowledge the right’s perspective, it limits the left’s ability to front more effective arguments.

Importantly, to many Moore-voting Alabama conservatives, support for Moore did not seem like support for pedophilia. For one thing, their distrust of the media led some of them to doubt the accuracy of reports on Moore’s history. The GOP exploited their constituents’ skepticism about mainstream journalism—an ongoing problem which Democrats need to address more meaningfully. A poll from December showed that 71% of Alabama Republicans believed that the allegations against Moore were false—the product of a media conspiracy and the untrustworthy nature of the female psyche. It was not, then, that they were fine with sexual predators, but that they dismissed the story alleging that Roy Moore was one. (A small sliver of voters did think that accusations against Moore were true but voted for him anyway.) Suggesting that Alabama Republicans are “fine with pedophilia” misidentifies what the problems are, then. In fact, the issues that Democrats need to confront are (1) disbelief in women’s accounts of sexual misconduct, and (2) a lack of trust in the press. These are both difficult barriers to overcome, but they’re considerably more tangible and assailable obstacles than the vague notion that “Republicans love pedophiles.”

Crucially, many Republicans also considered Moore to be the “lesser of two evils” and a better standard-bearer for the conservative agenda than his opponent. Certainly, Democrats can understand this impulse. History is replete with examples of Democrats for whom we’ve held our noses and voted. Just recently, in the lead-up to 2016, leftists who drew attention to America’s Clinton-backed intervention in Libya—an intervention which, among other horrors, has contributed to the creation of shocking slave markets—were told that what really mattered was getting a Democrat in the White House and liberals on the Supreme Court. Following the nineties-era rape allegations against President Clinton, he was defended on similar grounds. And some commentators insisted Al Franken should retain his Senate seat for the good of the party, without drawing any firm conclusions about exactly how much sexual abuse by a public official we should let slide so long as they are on our side.

The same logic kept a number of voters from inquiring too much into the allegations against Moore: true or false, he’s still a Republican. Sometimes this was driven by an absolute opposition to abortion: for those who see the practice as mass murder, even acts of gross sexual misconduct by a GOP politician won’t justify voting for a pro-choice alternative. While the instinct to highlight Moore’s history was correct since it made voting for him more difficult and allowed Doug Jones to eke out a victory, pretending that the GOP “supported” sexual assault likely had a different effect: to raise hackles and further embed already dug-in heels. Why? Because a bad-faith attack over shared values has never persuaded anyone. (When, dear progressive, were you last swayed by a Republican who claimed you simply don’t care about the troops?)

By contrast, pointing out that a vote for Moore meant prioritizing low taxes over the safety of young girls clearly outlines the moral stakes of the choice at hand and gives the voter the opportunity to opt for what’s right. The shaming option berates the voter for being deplorable. The guilting option provides an opportunity for redemption.

The shame question is also present in the endless debates around the role that race played in Trump’s election. Many of the progressives who emphasize racism as the only relevant factor in Trump’s appeal, and who downplay economic causes, have insisted that, at best, Trump voters pursued their (perceived) self-interest without regard to the human collateral they left in their wake: At worst, they felt Trump’s antipathy toward brown people was a plus. Framed this way, shaming makes perfect sense. Yet a shaming approach can make us indifferent to the complex human factors that underlie decisions we detest. Millions of white Americans have undergone economic hardship in the decade following the great recession, even though certain ethnic minorities suffered disproportionately from the recession. (Black Americans, for example, lost 40% of our accumulated wealth, which already represented a small fraction of white wealth). And many of the Trump voters who feel unheard and unrecognized by blue America may have a sliver of a point: The “establishment” of both parties has long abandoned labor and under-responded to issues that disproportionately affect rural communities, like the opioid crisis. (Keep in mind: many, not all, or even necessarily “most.” Trump’s base was notably more affluent and less economically stressed than Hillary’s.) Applying shame to an entire category of people, rather than conducting a more nuanced assessment of why people feel the way they do and did what they did, means we might miss those among the blameworthy who might be identified as something more mutable, more persuadable than a “deplorable”—someone who might be convinced to join our side next time around.

If shaming feels cathartic, but is counterproductive to the goal of changing hearts and minds—which is, after all, indispensable for political success—perhaps we should shift from shame to guilt. If we narrow the focus from castigating the deplorable person to rebuking the deplorable belief, might we expand our appeal? Would it help preserve egos and tamp tempers to “hate the sin and not the sinner”? What if instead of satisfying but glib remarks about how voters in coal country deserve to lose their health care for being racists, we instead said: “Trump’s policies have been a direct attack on the working class. They were right to shake things up, but they should get something better than the status quo, not worse”?

This is the message that Michigan gubernatorial candidate Abdul El-Sayed has been using to win votes for a staunchly leftist agenda in a state that voted for Trump. “The vote for Trump was not a vote for hope or a vote of inspiration, it was a vote of cynicism and frustration with the status quo,” El-Sayed says. “They didn’t vote for Trump because of some animus for Muslims, they voted for Donald Trump because they felt that he was at least speaking to an experience that they faced.” El-Sayed’s own uncle voted for Trump: “This is a guy who would take us water skiing in the summers and snowmobiling in the winters, and he learned to prepare venison Halal so that my family could eat it. He wasn’t motivated by some racial animus.” We may agree or disagree with El-Sayed’s actual analysis; perhaps one thinks he is too naïve, though as a Muslim candidate in the Rust Belt he likely has few illusions about American Islamophobia. But as a means of garnering political support for a left agenda, it’s more effective to tell El-Sayed’s uncle that he made a poor judgment that will hurt those like his nephew than to tell him he is a callous racist who doesn’t care about his family as much as we, the virtuous, do.

Sarah Silverman has recently embarked on a project to use empathy as a more effective means of advancing progressivism with her show I Love You, America. On it, she substitutes compassion for condescension, and where other comedians are sardonic—using Trump voters as punchlines—Silverman is sympathetic to a degree that is, at times, frustrating, but is ultimately more constructive than the alternative. In the first episode, Silverman managed to pass the “beer test” with a conservative family—a hurdle Hillary struggled to clear in 2016—and she didn’t do it by pointing out their ignorance. She did it by presenting them with a personification of liberalism so gracious and warm that it rerouted their anger to empathy. And empathy is a quicker route to change.

In identifying the use of shaming tactics as the cause of some of the defensiveness, anger, and violence we’ve seen from the right, I am not excusing that behavior. Nor do I mean to suggest that Trump supporters don’t “deserve” to be shamed; the shaming itself is but meager retribution for the real harms which have resulted from the right’s actions at the ballot box. Empathy has to go both ways: you have to understand why those who use shaming do it, and why the left’s moral outrage isn’t simply—as the right often suggests it is—an effort to seem righteous and superior: it comes from being genuinely disturbed and angered by the way marginalized people are treated.

But by unpacking the role shame plays in our political discourse, we can use our words more strategically and become better equipped to move the country in the right (i.e. left) direction. As Trump’s popularity continues to wane, and his supporters are increasingly confronted with the reality that his campaign promises were worth less than the worthless news networks who profited from them, it might be worth using the lessons of social psychology to clear a path to greater mutual understanding. We should focus our criticisms on Trump’s specific beliefs and their human consequences rather than his integrity (or lack thereof). No one was ever reformed by a lecture about how racist they are. Save the “How could anyone…”s for Twitter, and don’t underestimate the persuasive power of laying down a carefully calculated guilt trip.

Humanism is hard. But it’s easier than four more years.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation or purchasing a subscription. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.

This article originally appeared in our Jan/Feb 2018 print edition: