Can The Left Reclaim “Security”?

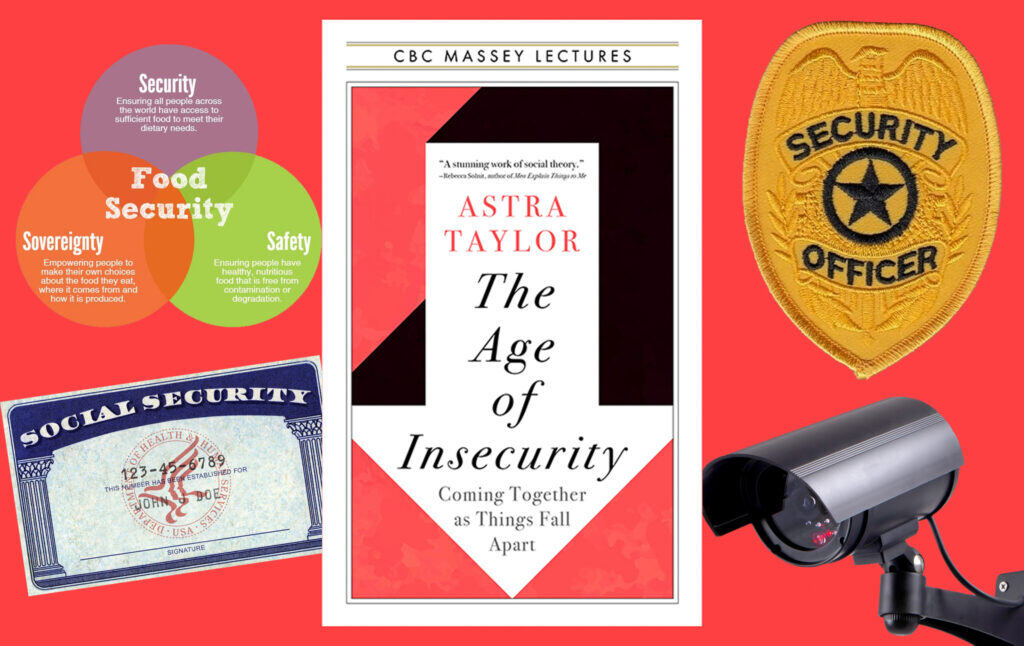

Astra Taylor argues we live in an “age of insecurity.” Understanding this may be crucial to thinking about how we can address Americans’ widespread pessimism.

I don’t often come away from books feeling like they’ve changed the way I think, but Astra Taylor’s The Age of Insecurity made me feel I understood something obvious that I had overlooked before.

First: there’s an ongoing debate among political types about why American voters rate the Biden economy so poorly. The public’s negative views are threatening Biden’s reelection chances, but many economists argue that people are not giving Biden enough credit. CNN tells us that “By almost any objective measure, Americans are doing much better economically than they were nearly three years ago, when President Joe Biden took office.” Yet a majority say Biden has made economic conditions worse. Economist Justin Wolfers says that “there’s this disjunction between reality and perception that’s as large as I’ve ever seen in my career.” Some supporters of the president are frustrated that he isn’t getting more credit.

We on the left have plenty of explanations for why voters aren’t rating Biden highly on economics. My colleague Stephen Prager has written an excellent overview of what is overlooked by an economic analysis that only considers broad factors like GDP and unemployment. Matt Bruenig looks at income and wealth and shows that a lot of people don’t have much to celebrate.

But reading Astra Taylor’s book helped me better understand another critical factor here: security. Even when people’s present circumstances are okay, they have to feel confident that it’s not all just going to evaporate tomorrow. It’s not enough to have a good income if you’re constantly anxious that you could lose your job. It’s not enough to have good health insurance if you are worried that every year you could get dropped from your plan. And the job of a U.S. president is not just to improve economic numbers but to instill confidence that the future will be better than the past, that everything is not just going to fall to pieces.

Taylor tells us that securitas, in Latin, meant equanimity and calm, a kind of imperturbability. None of us can achieve perfect security, she says, because all of us are mortal and face a kind of inherent existential insecurity. Life could end any day, even if we expect it won’t. But Taylor argues that there are also plenty of manufactured insecurities that make us anxious and fearful even if we don’t need to.

In the workplace, employers make workers feel insecure as a “discipline device.” If you’re afraid of getting laid off or fired, if you feel replaceable, then even if your job is a good one, you don’t necessarily feel like your economic circumstances are great, because they feel precarious. Similarly, if you can pay your rent today, but your landlord could hike it tomorrow, then even having money in your savings account doesn’t necessarily feel like having more money, because it’s at risk of disappearing. I felt this personally recently. I got an unexpected check in the mail that gave me a boost to my savings. I should have been delighted. But because I am naturally economically pessimistic, I felt like it was only a matter of time until some unexpected expense took my good fortune away from me. Sure enough, an unexpected medical bill soon arrived (a year late, long after I’d thought the matter was dealt with). Then my insurance company told me my health insurance plan was being canceled for next year. My savings may be higher than they were, but my feelings of anxiety are also much higher.

I suspect that the pandemic made a lot of people much more aware of risk and destroyed their feelings of security. They saw that everything could change overnight, that the things we rely on and see as permanent are in fact all temporary and very fragile. This is especially true in a capitalist economy, where people can wake up one day and be told their job has been shipped overseas or is now being done by a machine, and there’s nothing they can do about it.

Americans are feeling pessimistic about the future. And frankly, they have good reason. There is a greater risk than at any point since the Cold War of a catastrophic war between great powers. AI technology is being deployed by profit-maximizing Silicon Valley companies that have zero regard for the possible negative social effects of their actions. The climate catastrophe threatens to spiral out of control. U.S. support for Israel’s brutal pummeling of Gaza is almost certain to increase the long-term threat of attacks on this country by non-state actors. (I don’t like to use the word “terrorism,” because it’s a term we only apply to things done to us, never when we and our allies do the same things to others.)

This is already a country where lots of people feel afraid all the time. Many buy guns and turn their homes into fortresses. The right wins elections by stoking panic that hordes of immigrants are coming, or that antifa is going to burn down your city. Even when things are actually okay, people can feel terrified that any moment, it will all go to pieces. And what conservative politicians sell to the people they scare is the possibility of security. National security. Homeland security. The security of your property.

The right-wing conception of security is often illusory, though. Buying a gun does not actually make you more safe. In fact, in search of security, people can destroy everything they’re trying to keep secure. Consider the tragic stories of people who mistake their own family members for intruders and end up shooting them, sometimes fatally. These are people who thought they were protecting their families; instead, they became the very thing they were trying to stop. Likewise, on the national level, the brutal U.S. response to the 9/11 attacks created more ire in the Muslim world and motivated more attackers. I suspect that Israel’s response to Oct. 7 is going to be similar, with its mass killing of Gazans helping to radicalize and recruit the next generation of Hamas (and other) militants.

What Taylor argues in The Age of Insecurity is that we on the left can (and need to) offer a different, better conception of security. We can speak to people’s fears and anxieties. We can’t promise to keep them safe from all of life’s vicissitudes, but we can certainly eliminate many of the “manufactured” insecurities in our society. We can make it so that you don’t have to be afraid that if you need an ambulance, you’ll get an enormous bill. We can make it so that going to school doesn’t leave you indentured for decades afterwards. We can guarantee a job or a basic income. We can protect people against unexpected rent hikes. We can make it so they don’t have to be afraid that if the police come, they’ll shoot the person who called them.

Those defending Biden’s economic record would argue that people have become more secure in the Biden economy. After all, when there are plenty of job opportunities, you have less to fear from losing work. But I think a lot of people look out at the long-term future of this country, and are worried it does not look good. Some even predict a coming “civil war.” (Personally I think that’s pretty implausible.)

I was recently reading a fascinating book from the early ’60s. It’s called Fundamentals of Marxism-Leninism, and it was published by the Soviet Union as a kind of introductory manual for their official ideology. Now, I’m no Marxist-Leninist, and the Soviet Union was built on lies and violence, but one of the extraordinary things about the text is that its writers seemed to hold a genuine optimism about the future they wanted to build. They speak of how they are achieving the “dream of general sufficiency and abundance, freedom and equality, peace, brotherhood, and co-operation of people.” They predict:

“[Under communism] the creation of an interesting, happy, and joyous life for all becomes a mighty, all-conquering motive of human activity….A powerful basis for production, greater power over the forces of nature, a just and rational social system, the consciousness and lofty moral qualities of people—all this makes it possible to realise the most radiant dreams of a perfect society….The victory of communism enables people not only to produce in abundance everything necessary for their life, but also to free society from all manifestations of inhumanity: wars, ruthless struggle within society and injustice, ignorance, crime, and vice. Violence and self-interest, hypocrisy and egoism, perfidy and vainglory, will vanish for ever from the relations between people and between nations. This is how Communists conceive the triumph of the genuine, real humanism which will prevail in the future communist society.”

This looks ridiculous to us today. They were going to eliminate human hypocrisy forever by changing the ownership of the means of production? Okay. I don’t think we need to revive this kind of dangerously naive utopian prophesying. But I do read passages like this and wish that today we had an ambitious vision of an uplifting future worth fighting for. I think this is an important part of what economists puzzled by disappointment with Biden are missing. Yes, a lot of the positive numbers they cite mask an economy that actually doesn’t work for a whole lot of people. (Try telling the vast numbers of homeless people that they should be grateful for improved GDP numbers.) But also: people need to feel confident that they are moving toward a better future, that they’re becoming more secure, that they don’t have to worry as much about giant looming risks. They need to not be afraid. They need to be able to approach what comes next with a sense of confidence and excitement.

Taylor sees this as a time characterized by extreme insecurity, and I think she’s right to frame it that way. Even what precious things we do have seem ephemeral, constantly at risk. Society doesn’t feel stable or dependable, and it doesn’t feel that way because it isn’t. There’s no reason we couldn’t have another pandemic. The consequences of climate change are going to hit us harder and harder. Even if people can afford a house, it might just burn down (without much in the way of “security” from homeowner’s insurance). Taylor is right that leftists can’t cede the concept of security to the right, who will tell people that taller walls, booby-trapped buoys, and lots of guns are the way to achieve security. In fact, it’s things, like, well, Social Security, which keeps millions out of poverty. Nothing would more drastically increase our security than the implementation of a 21st century economic bill of rights.

The people shielded behind those walls are not going to stop feeling afraid. We need to offer a genuine sense of safety that mitigates preventable risks: the risk of losing your home, the risk of going bankrupt, the risk of war, etc. We can never promise complete security but we can try to end the “age of insecurity.”