Exposing the Many Layers of Injustice In the US Criminal Punishment System

From the unmatched power of prosecutors to the political corruption of judges, our criminal punishment system is rife with injustice.

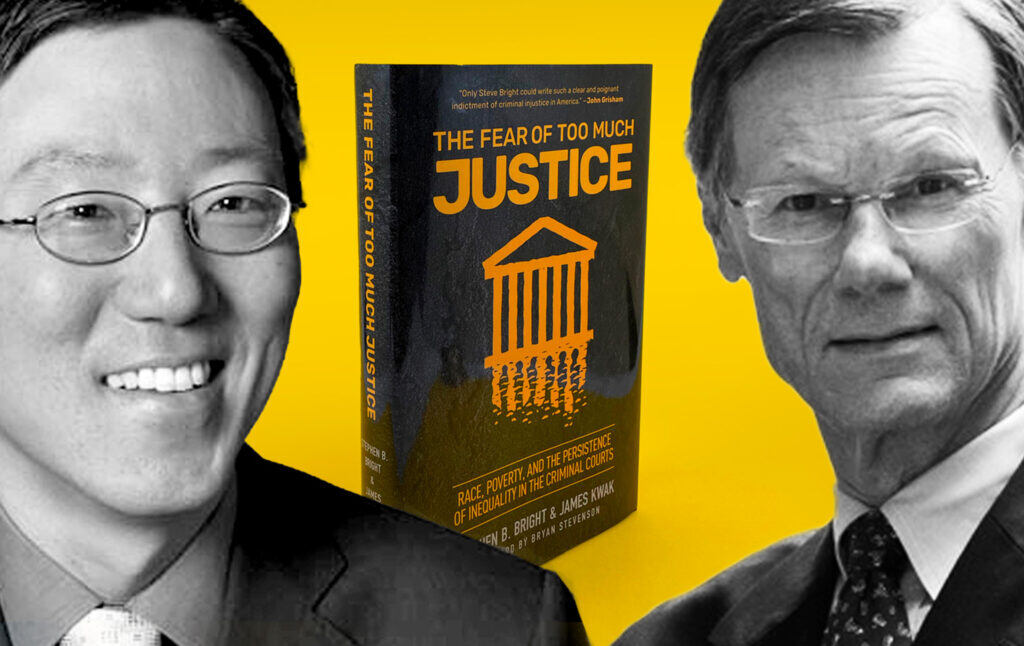

Today we are joined by Stephen Bright and James Kwak to discuss their new book The Fear of Too Much Justice: Race, Poverty, and the Persistence of Inequality in the Criminal Courts. The book is a comprehensive primer on the problems with the American criminal court system, from the power of prosecutors to the underfunding of public defenders to the biases of judges to the obstacles to getting a wrongful conviction overturned. Bryan Stevenson calls it “an urgently needed analysis of our collective failure to confront and overcome racial bias and bigotry, the abuse of power, and the multiple ways in which the death penalty’s profound unfairness requires its abolition.”

This conversation originally appeared on the Current Affairs podcast. It has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Robinson

Let’s start with the title of the book: what is “the fear of too much justice”?

Bright

In 1987, the Supreme Court considered a case involving the racial disparities in the infliction of the death penalty in Georgia. The evidence in that case showed that if the victim in the case was white, there was a much greater likelihood death would be imposed if the defendant was Black, and if you had a case, like the one that was before the court, involving a black defendant accused and convicted of a crime against the white victim, the likelihood was much greater that you would get the death penalty. It was a very close case, with the majority opinion five to four. Justice Powell wrote for the majority: if we deal with racial disparities in the infliction of the death penalty, wouldn’t we have to deal with racial disparities in all the other kinds of crimes and the criminal courts? And Justice Brennan, in his dissent, said this was a “fear of too much justice.” That explains a lot of things besides just the tolerance of racial discrimination, not only in the death penalty but in jury selection and other kinds of cases. Our argument is that that’s what the court should be doing. We should be dealing with those issues and deciding them rather than being afraid to tackle them.

Robinson

You open the book with a quote from Winston Churchill who says that, in fact, “the mood and temper of the public in regard to the treatment of crime and criminals is one of the most unfailing tests of the civilization of any country.” Professor Kwak, if that is the test of civilization, how is our civilization doing?

Kwak

I think, as you can imagine, we’re doing quite poorly. I think Churchill was right about some things and wrong about some things, but I think on this issue he was definitely right. As a country, we like to pride ourselves on upholding civil rights and human rights. We like to think that human rights are a problem that other countries have, not a problem that we have. But I think that, as Churchill said, the real test is how a society treats people who are often poor, often from broken families, who often have done bad things and are essentially defenseless against the power of the state. And I think that our country does pretty badly, especially when you consider people who are poor people of color swept up in the criminal legal system.

We know that if you have a lot of money, you can mount a good defense. But one of the problems with the criminal legal system is the way that we treat people who can’t afford good lawyers and good representation. So, Steve talked about the fear of too much justice in the context of the death penalty—that’s one extreme of the criminal legal system. If we look at the other extreme, we have hundreds of thousands of people who are arrested and charged with relatively minor offenses, either misdemeanors or felonies, that could get them a few years in prison. And, as we can discuss more later, in most states, cities and counties fail to provide most of these people with effective lawyers who have the time to do their jobs well, and why don’t they? One reason is the fear of too much justice. If everyone accused of a crime had representation as good as rich people, or if every one of them had someone as good as Steve Bright to be their lawyer, the machinery of the criminal legal system as we know it would go into a halt. We would not have 95 percent of cases result with plea bargains. We would have many more trials, and the systems just aren’t equipped for that. So, that’s one reason. It’s not the only reason, but it’s one reason why we tolerate this level of inequality in the criminal legal system.

Robinson

Your book goes through many different parts of the criminal legal system, from judges to prosecutors to public defenders. You have a chapter on mental illness and criminal punishment, on fines and fees. I want to go through some of these different parts. You take each apart and show where the injustices come in and how we might do better. You start with the prosecutor, and you have a quote in here that might be counterintuitive. You write, “the prosecutor is clearly the most powerful actor in the criminal legal system.” I think it might be the instinct of an ordinary person that the judge is the most powerful person in the criminal legal system because, after all, the prosecutor can only make an argument and the judge then decides whether to accept that argument or not. So, professor Bright, what leads you to say, pretty definitively, that the prosecutor is, in fact, the most powerful actor in the criminal legal system?

Bright

For one thing, the prosecutor can decide not to charge at all, and there’s absolutely nothing a judge can do about that. Or a prosecutor can decide to seek the death penalty in a case that really should not be a death penalty case, and there’s nothing a judge can do about that, either. We have a couple of examples of women facing the death penalty. Kelly Gissendaner was one. She and her boyfriend had conspired to murder her husband. They got caught, and the prosecutor told them both, if you plead guilty and testify against the other, you’ll get a life sentence and will be eligible for parole after a few years. The boyfriend took it and testified against her; she did not. She went to trial and got the death penalty. It was a case almost no other prosecutor in Georgia or even anywhere else in the country would have sought the death penalty for, but the prosecutor had the discretion to do it.

Many years later, she had been a model prisoner and had gotten a divinity degree. There were many people, including the two children of the marriage—of course, their father was the victim, and their mother was now the person to be executed—desperately pled for their mother not to be executed. But she didn’t take the plea, and so she was put to death by the state of Georgia.

Only the prosecutor has the ability to decide who gets the death penalty, who gets mandatory minimums, and who’s charged with a felony as opposed to a less serious crime. The prosecutor also has another power that I think many people don’t think about. It’s a power that no other person in the court system has: the ability to reward people for testifying the way they want them to. In other words, the person goes to the prosecutor—they may be charged for burglary or robbery, whatever it may be—and says, if you dismiss my charges, I will testify that the defendant in this case admitted to me that he did it. These are notoriously unreliable people, but they’re called upon all the time. There are many people who really make a career out of being jailhouse snitches. And again, there’s nothing a judge can do about that. The prosecutor decides to cut a deal with them by either dismissing their charges or giving them less serious charges in exchange for their testimony. And unfortunately, many people who are in prison today, and many people on death row, got there because of a trial where one of these jailhouse snitches testified.

Kwak

I’d like to add one more thing. Steve talked about the prosecutor’s discretion to make charging decisions to seek the death penalty, and that’s obviously very important in life or death cases. Again, it’s equally important in small cases. The way most small cases are resolved is the prosecutor says, based on the facts that I can probably prove, I could charge you with these two felonies which might have a mandatory enhancement, and you’ll get 10 to 15 years in prison, or I can charge you with one misdemeanor, and you’ll get six months in prison and three years of probation. The defendant typically takes the deal, often because they don’t have a lawyer who is equipped to fight the deal. They present it to the judge, and the judge has to take it. There are very rare cases where a judge will inquire into a plea bargain. But when we’re talking about garden variety criminal convictions, the judges are just rubber-stamping them. And it’s the prosecutor who decides the sentence, not the judge, because the sentence is determined by the charges and by the negotiation.

Robinson

Professor Kwak, you are also the author of a wonderful book that I’ve enjoyed for a while called Economism, which is a critique of the overuse of economic concepts in our society, and I think you’re right on that. But as I was reading this book, I couldn’t help but think that the common assertion among economists that incentives rule the world has some truth here. You highlight numerous instances in which there are just bad incentives all through this system, in which judges have bad incentives, people have an incentive to plead guilty, and people have an incentive to lie on the stand. There are many ways in which people are pushed into bad behavior.

Kwak

Yes. I agree with that. I think that one of the points of Economism was that economic thinking in itself is not bad, and thinking about the importance of incentives is not bad. It’s just that in certain policy contexts it gets taken too far. We don’t discuss this in the book because, frankly, no one takes it seriously anymore, but in the 1960s and 1970s, one of these right-wing Chicago School economists said that crime is a function of incentives: what criminals do or what people thinking of committing a crime do is think, what’s the percentage chance I’ll get caught? They multiply that by the sentence they think they’ll get, and they say, I’m going to go ahead and commit this crime. And that is absolutely preposterous—in small cases, big cases, death cases. If you look at the facts behind these events, it’s clear that people are not making rational estimations of how much punishment they will get.

But I think that when we talk about how cases are disposed of, as you say, incentives are very important. We’ve talked about the incentives involved in plea bargaining. The defendant knows that if they insist on going to trial, firstly, they can get a much larger sentence, and secondly, the prosecutors are much better equipped to try the case. Incentives matter.

Another situation we talk about is prosecutors and judges. Virtually every district attorney in the country is elected; judges are elected in a majority of states. Given the politics of crime and the law, prosecutors pose as basically people who put criminals away, and judges know that if they uphold defendants’ constitutional rights in high-profile cases, they may face attack ads in the next election. So, I agree with you that incentives do matter a lot in various parts of the system.

Robinson

Let’s talk a little bit more about judges and the ways in which judicial independence is actually quite limited. We think the judge has autonomy, but a judge can, in fact, be punished for leniency.

Bright

Examples abound of judges who were voted out of office because a campaign was run against them saying that they were soft on crime. Many times, those campaigns weren’t even fair; the judge was only one of several judges who ruled a certain way on a state Supreme Court and got voted out of office as a result of that. At the local level, one of the things that we see that’s very disturbing is, in many places still today, judges appoint lawyers for people accused of crimes and very often they give people an incompetent lawyer.

We know that in Houston, for example, when someone runs for judge, the lawyers there contribute a lot of money to the judges’ campaigns. And once one is elected judge, many of them then appoint those lawyers to cases, including death penalty cases, and then pay them very generously for often doing very poor work on behalf of their clients. In other words, it’s a political patronage system. It’s not a system based upon giving people a fair trial and a zealous lawyer or any of the things that we expect the system to provide.

Robinson

There is an extraordinary quote from a former Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court who, after she retired, wrote, “I was Alabama’s top judge, I’m ashamed by what I had to do to get there.” It can be quite explicit. She said, “Donors want clarity and certainty even that the judicial candidates they support view the world as they do and will rule accordingly.” We talk about money in politics, but generally, I feel like judicial elections are overlooked in that.

Kwak

Yes, they are. Somebody once said, the people with money to spend have figured out that it’s a lot cheaper to buy a Supreme Court Justice than to buy a whole state legislature, and often the Justice can do a lot more for you. So, we’ve seen in the past 30 to 40 years two things. One is obviously increasing polarization in American politics, and an increasing attitude on both sides—I think more with Republicans, but to some extent on both sides—to see every piece of the governmental system as a battleground to be fought over. And then we’ve also seen the realization that judges, particularly State Supreme Court Justices, play a fundamental role. This is common knowledge now. You think about the Supreme Court of Wisconsin, Supreme Court of North Carolina, and the swing states, everyone knows that these are extremely important political institutions that will decide a huge variety of cases. However, one thing we talked about in the book is that when it comes to running a campaign against a judge, nothing works as well as demonizing them as being soft on crime. So, judges get attacked, as Steve said, for basically making correct decisions, calling out prosecutorial misconduct that requires a new trial for somebody who will probably be convicted again and probably go back to jail. But, simply ruling on behalf of the defendant can become a fatal error from a political perspective, and that’s certainly contributed to the polarization of the judicial system, and also to the hesitancy that judges may have to uphold constitutional rights.

Robinson

There was one other thing I wanted to ask you about prosecutors. I think people have heard, or it’s become a little more common knowledge now, that the plea-bargaining process can be quite coercive. But one of the things that you discuss in this book that, I think, is less well understood by the public is the level of control of information that prosecutors have and the way in which evidence of innocence can be concealed. Could you talk about that a little bit, going back to how the prosecutor is the most powerful actor in the system? We discussed their charging decisions and plea agreements, but could you discuss the information that they have control over?

Bright

Sure, and that’s a very good point. Again, what many people don’t understand is that in many states, all the work that the police have done—all the investigation, the witness interviews, and the grand jury work—the prosecutor has all that and, in many places, doesn’t have to share it. In North Carolina, they passed a law at some point that said after a death penalty case, information in the prosecution file had to be disclosed. And about 10 years after that, ten different people who had been sentenced to death were given new trials because of information that was in the prosecution file that had never been disclosed to the lawyers for those people. The first of those, Alan Gell, went to trial and was acquitted in a very short period of time and clearly was not guilty of the crime. After that, North Carolina passed a law that said that before trial, the prosecution had to disclose everything in the police and prosecution files, and that’s something that really, in this day and age, ought to be required everywhere. In a settle case, where we’re talking about a lot of money, everything is disclosed—their depositions, their change of documents, their requests for admission. There’s all this information so that by the time of trial, both sides know everything there is to know about that dispute. And yet, in criminal cases, where we’re talking about life and liberty, we still have trial by ambush in many places. We see that one of the results of that is, as you note, the conviction of innocent people.

Kwak

As you know, there have been rules since the 1960s saying that prosecutors have to turn over potentially exculpatory evidence to the defense attorney. So, we have that principle in the system, but the problem since the 1960s has been it’s up to the prosecutor to decide whether evidence is favorable to the defendant or not. And prosecutors, first, have a bias in thinking—they think the guy is guilty and that it’s not exculpatory information. And secondly, the penalties for failing to turn it over to the prosecutor personally are generally zero. So, we have a system that depends on the intentions and the behavior of the prosecutor, and it’s a system that clearly is not going to work, which is why I think North Carolina did the right thing by requiring full file disclosure.

Robinson

It’s a little paradoxical because presumably, if they actually thought it was exculpatory, they wouldn’t be prosecuting the person. There was a case here in New Orleans I wanted to mention. Professor Bright, when I took your class, John Thompson came to speak to our class. He was kept on death row for many years because the office of Harry Connick Sr. had failed to turn over exculpatory evidence. Of course, there’s not much you can do about it because you don’t know what you don’t know.

Bright

John Thompson is a sobering case because he came within a very short time; he had an execution date and was going to be put to death. The law firm that had taken his case sent somebody to take one last look through the files, and lo and behold, found this document that showed the blood type of the assailant in the case, and it wasn’t John Thompson’s blood type. So, at the very last minute, he was exonerated. He could have very easily been put to death either because that document was never found or because they didn’t even look for it in the first place. So again, it’s a very sobering case.

And tragically, there were a number of other cases out of the New Orleans district attorney’s office of people who were later exonerated. Curtis Lee Kyles is one that comes to mind. He had several trials, hung juries, was finally convicted, and then the Supreme Court of the United States said failure to disclose certain evidence required him to get a new trial and, ultimately, charges were dismissed.

Robinson

Last time you were on a program, professor Bright, we discussed extensively the quality of counsel available to poor people in this country. There’s a lot on that topic in the book, so I don’t want to dwell too much on it in this conversation—people can go and listen to our previous conversation about that. I want to talk about some of these other parts of the system today. In particular, I’d like to talk about how difficult it is to get an error fixed. You have this quote, I think it’s from Justice Blackmun, about the “Byzantine morass of arbitrary, unnecessary, and unjustifiable impediments to the vindication of federal rights.” One of the things I remember most from your death penalty course is just how complicated and difficult it is, even when there has been an obvious failure or an obvious injustice in violation of proper legal procedure, to get your actual guaranteed rights vindicated.

Bright

Yes. Very often, the reason the rights were vindicated was because it’s something that the prosecution did. And yet, when it was becoming clear that a lot of death penalty cases were going to be set aside because of constitutional violations, the Supreme Court began just making up out of whole cloth all these procedural requirements, and then saying because the lawyer didn’t object, or the lawyer didn’t do one thing or another, we’re not going to look at the particular issue in the case. And they just kept tightening that up and got it tighter and tighter and tighter until now, very often, the courts just won’t even examine the constitutional violation that took place in the case.

Robinson

Professor Kwak, you document many instances in the book of things that have obviously been done wrong, and ways in which people have been treated unfairly or had their rights violated, but they struggle to actually get a remedy. Could you give us some examples?

Kwak

I think that the most fertile ground for that kind of tragedy is the ineffectiveness of counsel. We talked at length—you’ve talked about this with Steve in the past—about the poor representation that many people have on trial and on direct appeal, but one would think that those errors could be fixed. If your lawyer is drunk or sleeps in court, these seem like pretty cut and dry cases. But the challenge is that, although the Supreme Court said in the 1960s that you have the right to a lawyer if you’re facing any potential loss of liberty, it wasn’t until the Strickland case in 1985, I believe, that the Supreme Court had to decide what it meant to have an effective lawyer. And in Strickland, the Supreme Court set the bar very low for the performance of a lawyer. They said lawyers are presumed to be competent and decisions that they make are presumed to be strategic.

So, for example, the decision not to cross-examine any of the prosecution’s witnesses could be presumed to be strategic. In other cases, the courts have said that, essentially, not putting on any mitigating evidence in the penalty phase of the death sentence trial was strategic. So firstly, if you’re trying to prove that you had an incompetent lawyer, you have to prove that they were really, really bad, and then secondly, you have to prove that a better lawyer would have made a difference, which is extremely hard to prove. And the other thing I should have said first is that to do all this, you need a good lawyer. Ineffectiveness claims are typically made in state post-conviction proceedings, where you have no right to a lawyer. For example, in certain states, states will give you a lawyer for post-conviction petition in certain kinds of cases such as death penalty cases.

So, to wrap up the previous point, most people who have been convicted because of incompetent lawyers don’t have a lawyer to make a claim of ineffectiveness. Some of them do, but that lawyer doesn’t necessarily have to be competent because the right to counsel does not apply to a lawyer provided to you for post-conviction proceedings by a state. For example, in Texas, that lawyer just essentially has to be bar certified and not be right out of law school to be considered competent, and even if they then proceed to behave incompetently, you have no claim. So, that’s just one of the many ways in which the U.S. Supreme Court has made it difficult to fix errors.

Another major problem was the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, which said that federal courts have to show great deference to decisions of state courts and also tightened up the ability to get federal reviews. For many decades, the federal courts were the avenue by which people who had been, for example, sentenced to death in state courts could have the convictions overturned. Supreme Court decisions made since then have made it very, very difficult. So, it’s only once in a blue moon that state court decisions get overturned in federal court.

Robinson

As I understand it, professor Bright, you’ve taken numerous capital cases in your life. And I know that you have taken many appellate cases where you have had to work with the record of a bad trial lawyer and try to undo the damage that was done. I take it this is one of the reasons why you so heavily insisted on the need to make sure that everyone gets competent counsel at trial. It must have been just incredibly frustrating for you to look at the record of a case and know that you would have done it differently at the trial level but now you’re stuck.

Bright

Often you can look at a record and say that any competent lawyer would have done it differently. There are many places in this country, in particular the places sending plenty of people to death row like in Alabama and Texas and some other states, where there are no public defenders. Just some local lawyer is appointed to represent someone. And often these lawyers don’t even specialize in criminal law, let alone the subspecialty of capital defense, and you have lawyers who are just clueless, unfortunately. Unfortunately, you also have lawyers who have alcohol and drug addictions that show up in these cases many times. And as explained a moment ago, if you do come in later and try to show all the things that could have been done, all the facts that should have been proven, and all the questions that should have been asked, you basically substitute trial by judge for trial by jury. Because even if you show that the lawyer was very deficient and that the representation was totally unreasonable, the judges will say, we don’t think it would have made a difference, we think you would have been convicted anyway, or we think the client would have been sentenced to death anyway. There’s no way they would know—they weren’t there at the trial, they didn’t see the witnesses, they didn’t sit with the jury, and they don’t know how the jury assessed the case. But that’s the system that we have.

And so the first hurdle that a person has is getting a lawyer, and as James said a moment ago, many people who are convicted never have a lawyer to raise the competence of the lawyer they had at their trial. And then if you do—and more often it’s going to be in death penalty cases—this deference that the federal courts have for the state courts is also going to kick in so that an awful lot of very deficient representation is allowed to go on uncorrected.

Robinson

You’ve been talking there about the death penalty cases—obviously, the most serious category of cases—but you have in your book a lot of documentation of the everyday extraction of money from poor people by courts, by private prisons, and by a category of corporation that I didn’t know existed until reading the book, which is the probation company. I didn’t even know there were probation companies, but I feel like that is an industry that shouldn’t exist.

Kwak

This is a reflection, in part, on the nature of government in the United States. So, a couple of things have happened. One is that at the beginning of the 1980s—perhaps in the 1970s with Margaret Thatcher, but certainly in the 1980s with President Reagan—there has been a prevailing view in this country, held by most Republicans and I would say many Democrats, that the private sector can do things better than the government. So, given the choice, we should be outsourcing government functions to private companies. The other thing I’ll say about government in this country is that there is a lot of legal corruption at all levels of government. Legal corruption is essentially companies buying favors from politicians through legal means, such as contributions, lobbying campaigns, implicitly promising people jobs as lobbyists after they leave government, and so on. And so, when you add those things together, what do you get? You get private probation companies that contribute money to politics at the local and state level, and they convince, for example, the head of the Department of Corrections and a group of state legislators that probation functions should be outsourced to the private sector. And how does this work? If you have fines and fees that you can’t pay, the judge will say, that’s fine, you can pay over the next 12 months, but the money will be collected by this private probation company, and you have to pay them a fee of $40 a month for their “services.” So now, the poor person is even more in debt and is less likely to be able to pay off their fines and fees. When you add on probation fees, a year goes by, they’re behind on their debts, and they get sent to jail. That’s what happens.

I agree that in many parts of the economy, private companies do a good job of providing goods and services to customers who are willing to pay for them, but this is not one of them. The decision to hire a certain company to manage a prison is not being made by the people who are in prison; it’s being made by the Corrections Department or the legislature. And they’re making the decision not based on who can provide a safe environment and decent food at a reasonable cost; they’re doing it based on who takes them out to the nicest dinners when they’re in the state capitol. You can criticize our government as much as you want, but in the old days, probation officers were public employees whose job was to help you get your life together and make sure that you were able to get a job and keep it. Now, they are bill collectors who use the site of jail to extract money from families.

Robinson

I just want to look at one other area where you really document a pretty messed up part of our system. I think people have heard that jails and prisons are where we house the mentally ill in the United States, but what you document and expose is just how perverse it is to put people on trial who don’t even understand what is going on. You make what I think should be the uncontroversial assertion that people who cannot understand the legal system should not be processed through the courts. But they are processed through the courts every day.

Bright

Yes. This, again, goes to both the most serious cases and the most routine cases, as we’ve talked about throughout. The largest mental institution in any community is the local jail or the local prison. The prisons and jails have just become a dumping ground for homeless people who may have schizophrenia or bipolar disorder who are not being medicated or who don’t have families to look out for them and end up being arrested often on the pettiest kind of crimes.

I should say, parenthetically, that people who have mental disorders are much more likely to be victims of crimes than to be perpetrators of crimes. But there are times, tragically, when people with major mental disorders do commit serious crimes and are processed through the legal system. Maybe those people would not have been there if they had been dealt with appropriately in the community beforehand. They’re homeless because we don’t have any community mental health centers in most communities around the country. And so, as you say, there are people who are being tried, sent to prison, and even sent to death row who are profoundly mentally ill, don’t understand what’s going on, and really are not people who should be in prison. Instead, they should be in some sort of mental institution.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.