We Can’t Overstate the Danger of Tom Cotton’s “Might Makes Right” Foreign Policy

The hard-right Arkansas senator has just released a foreign policy manifesto. It’s an alarming justification for violently maintaining U.S. dominance over the rest of the world.

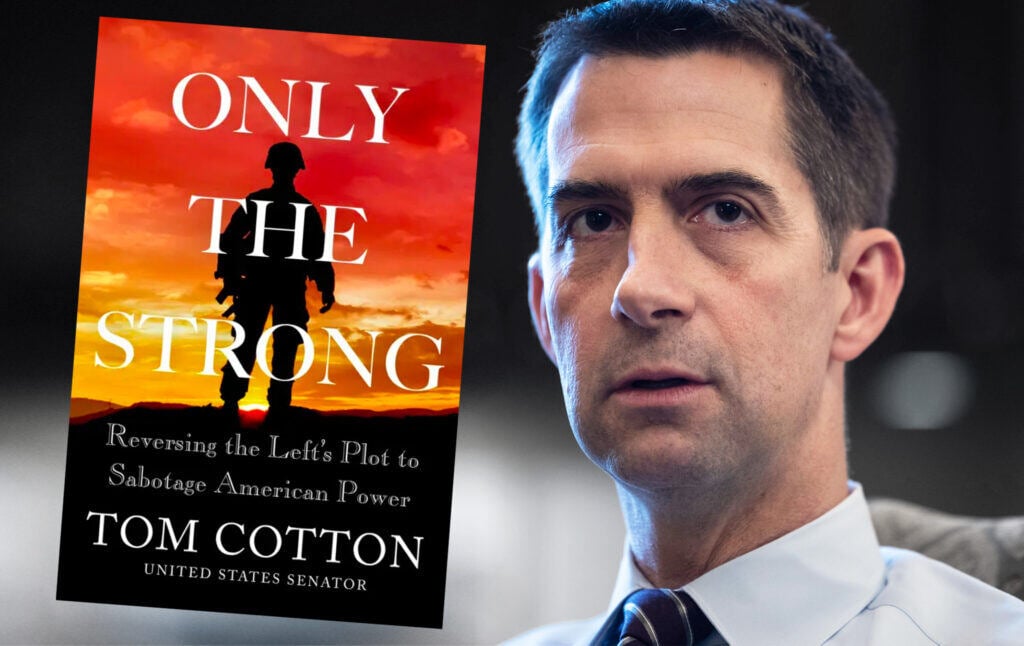

For those of us who argue that U.S. foreign policy is built around the preservation of global dominance rather than the spreading of democratic values, the new book written by Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR) provides some helpful supporting evidence. Only The Strong: Reversing The Left’s Plot to Sabotage American Power is a foreign policy manifesto that makes the case that U.S. Democrats are insufficiently militaristic. The core argument is laughable—from Truman annihilating Japanese civilians with atomic weapons to Obama’s drone strikes on helpless civilians, elected Democrats have never shown pacifistic tendencies or meaningfully curtailed American militarism. But in the course of making the argument, Cotton makes some useful, and terrifying, admissions about the core values that motivate those like him.

What’s jarring about reading Only The Strong is that it’s frank about facts that are usually concealed or obfuscated by defenders of U.S. foreign policy. All my life, I have seen critics like Noam Chomsky and Chris Hedges amassing exhaustive evidence to prove that, contrary to our leaders’ pronouncements, U.S. foreign policy is not based on values but on a desire to maintain power over the rest of the world. They argue that when presidents say we stand for the “rules-based international order,” what they mean is an order where we make the rules, running roughshod over international law, destroying other countries when it serves our interests, and generally being willing to use extreme levels of brutal violence in order to suppress any challenge to our position as the most powerful country in the world.

Most U.S. politicians would object to this argument. Barack Obama called the country “the greatest force for freedom and security that the world has ever known.” George W. Bush said that “we have no desire to dominate, no ambitions of empire. Our aim is a democratic peace.” Their story is that American power serves humanity as a whole, and that we are fundamentally a good country that acts out of benevolent motives. Ambassador Charles Bohlen said in 1969 that “one of the difficulties of explaining [American] policy” is that “our policy is not rooted in any national material interest of the United States, as most foreign policies of other countries in the past have been.”

Tom Cotton disagrees. Cotton’s response to the charge that the U.S. is a violent, selfish, and imperialist country is not “How dare you” but “Yes, and?” Only The Strong is remarkably blunt about asserting that the U.S. should not care about the fates of anyone else in the world, and that the job of American politicians is to follow what Adam Smith famously called the “vile maxim of the masters of mankind”: all for us and none for everybody else. “America must come first,” Cotton says. “The goal of American strategy is the safety, freedom, and prosperity of the American people.” For Cotton, that means that the central question of U.S. foreign policy is never “Is this legal?” or “Is this democratic?” or “Will this cause mass murder?” but rather “Is this good for the United States?” If something is good for the United States, it is good, period, regardless of how many millions of non-American lives it may destroy. He scorns those who put “humanity first,” and who think American power “should be deployed not to advance America’s interests, but rather to improve the social, economic, and political conditions of other nations and the world at large.”

Other politicians may try to give elaborate explanations of how the pursuit of the American “national interest” is actually in the interests of humanity itself. Not Cotton. To the charge that the U.S. supports hideous dictatorships when they are willing to serve our interests, Cotton says of course we do, in one of the most remarkably blunt quotes I have ever seen from a U.S. official:

No one ever mistook Diem, Somoza, the shah, or Mubarak for the Little Sisters of the Poor, … But what matters, in the end, is less whether a country is democratic or non-democratic, and more whether the country is pro-American or anti-American.

In other words, we care about democracy elsewhere only when doing so benefits us. If a dictator is pro-American, we will actually support their efforts to prevent democracy from breaking out. Cotton is highly critical of Barack Obama for abandoning U.S. support for Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak, saying that “no doubt Mubarak was authoritarian and repressive, but he largely supported America’s interests and he led the Arab world’s largest nation and cultural heartland.”

Cotton’s philosophy is roughly this: The world is full of dangerous enemies, and it is the job of the American government to pursue “America’s vital national interests.” In doing this, we have no moral obligation to care about international law or the fates of people in other countries. Let others worry about such things. The “liberal, rules-based international order,” he says, is “the kind of abstraction progressives love, but for which no soldier ever picked up a rifle and fought.” The U.S. priority is the U.S., period. We are to be a wholly sociopathic nation, interested only in ourselves. That interest is served through strength, which means threatening to kill anyone who gets in our way. When Cotton looks over American history, what he sees is this:

We went from a global backwater to an undisputed global champion. We possessed the world’s mightiest, most fearsome military. What’s more, we built the world’s largest and most dynamic economy, providing the highest standards of living ever known for the working man, with unlimited opportunity for success. And then we prevailed in the Cold War. America had fulfilled what Ronald Reagan called our “rendezvous with destiny”: we had become the greatest superpower in the history of the world.

Our job is to protect that status as the greatest superpower in the history of the world, using the threat of extreme violence if necessary, and Cotton is scornful of “globalist” presidents from Woodrow Wilson to Obama who have rhetorically indicated that they see the interests of others as mattering.

It is hard to overstate the extremity of Cotton’s militarism. He criticizes John F. Kennedy not for invading Cuba and trying to assassinate its leader, but for failing to try hard enough to invade Cuba and assassinate its leader. Cotton says that JFK should have deposed Castro because it was in our “interests” to do so, international law and respect for sovereignty being irrelevant. Cotton defends the 1953 U.S.-backed overthrow of the Iranian government of Mohammad Mosaddegh, saying that it was actually “Mossadegh who mounted a coup by clinging to office” instead of letting us depose him. Cotton’s view on the Vietnam War is that the United States was not aggressive enough (even though the U.S. sent half a million troops, dropped more bombs on Southeast Asia than had been dropped in all of World War II, and the war killed millions of Vietnamese people). Cotton says we should have continued to back the Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua, that there should be no respect for international legal institutions like the International Criminal Court (“foreign bureaucrats”), and that Woodrow Wilson should have prosecuted World War I with greater zeal (and framed it as a struggle for U.S. “interests” rather than a war for the future of democracy). Cotton believes that any admission that the U.S. has committed crimes or even made mistakes is “apologizing for America,” virtually tantamount to treason. Of course, he thinks Joe Biden should have stayed in Afghanistan and “won,” without giving any explanation as to how that could have been done.

Cotton retells American history as a story of Republicans keeping America safe and Democrats being weak and pacifistic. It’s a hard story to sustain, because so many awkward facts conflict with the narrative. If Democrats and The Left are pacifists trying to undermine the country’s strength, why did Democratic president Lyndon Johnson invade Vietnam, with leftists coming to despise Johnson? (Cotton’s answer, as we have seen, is that Johnson simply didn’t invade Vietnam hard enough.) Cotton does not say much about the Iraq War, probably because it was a murderous calamity that significantly undermines his arguments. The Bush administration followed Cotton’s philosophy exactly, showing strength through the use of military force and refusing to use diplomacy. The result was that they launched the most disastrous war of our century and destroyed a country. When the results of Cotton’s philosophy conflict with his view that militarism produces security and prosperity, he simply doesn’t discuss the facts.

Even before this book, Cotton had produced a record of public statements that put him on the hardest of the hard right. In the New York Times, he called for using the military to brutally crush Black Lives Matter protests. Guantanamo Bay detainees, who have never received due process of law, should nevertheless “rot in hell.” Cotton opposed limits on a president’s ability to authorize torture and attracted controversy for calling slavery a “necessary evil.”

In his book, Cotton adds to this record. He calls for the U.S. to fight China in a new Cold War, taking whatever extreme measures are necessary to prevail, including banning Chinese people from U.S. graduate programs in the sciences. He even seems to want more Chinese villains in movies. (“Have you noticed that there hasn’t been a movie with a Chinese villain in more than a decade? That’s because the studios are desperate for access to the Chinese market.” He is nostalgic for the good old days when “from Red Dawn to Rocky IV, Hollywood churned out patriotic, anti-Soviet hits.”)

He advocates a global nuclear arms race, tearing up arms control agreements and pushing us toward an even more dangerous world in which superpowers are constantly on the brink of annihilating each other with atomic weapons. (Cotton does point out, again uncommonly bluntly for a U.S. politician, that the notion we haven’t used nuclear weapons since World War II is wrong. “We use our nuclear weapons every single day and we have for seventy-seven years because their mere existence deters our enemies,” he writes.” In other words, you use a weapon when you threaten people with it, and this is what we do.) He of course believes we should immediately further militarize the border and step up deportations, reciting the common erroneous right-wing talking point that if a country doesn’t have a hard border it isn’t actually a country. (The U.S. did not have a militarized border for centuries but was nevertheless a country.)

Cotton argues that we must reject any attempt at international accountability for our crimes: “If we ever join the International Criminal Court, American troops could face trial and imprisonment by foreign bureaucrats.” (Left unsaid is that they would face trial if they committed war crimes, and that if we didn’t join the court they wouldn’t face trial for those war crimes.) Cotton is scathing about all international agreements, inevitably seeing them as “one-sided” attempts to constrain U.S. power. He is thrilled that the Kyoto Protocol was never ratified, because “had the Senate ratified Bill Clinton’s Kyoto Protocol on global warming, you would be paying much more to gas up your car and to heat your home.” He appears to view all international climate agreements as conspiracies by other countries to hamstring the U.S. and keep us from being prosperous and free. Cotton is clearly an outright climate change denier, because he doesn’t mention it, advocating massively escalating our production and use of fossil fuels, without any indication that this might have negative consequences.

All of this is insane and terrifying. Cotton, more so than any other Republican I have read (and I’ve read quite a few), comes across as a deranged authoritarian militarist who does not care in the least about democracy or human rights. But he is not a hypocrite, and he is not inconsistent. Cotton argues straightforwardly that the reason we should care about Taiwan is that semiconductors are produced there. (“That’s why it’s in our vital national interest to deter a Chinese invasion of Taiwan and encourage TSMC and its competitors to build new factories in America.”) This means that he, unlike Joe Biden, cannot be tripped up by questions like “Why do you support Ukraine but not Palestine?” or “Why do you care about Taiwan but not Yemen?” Cotton has a simple answer: because Israel and Taiwan are strategic partners of the U.S., and therefore we support them. Cotton does not play this game of pretending that we are involved in some noble struggle of “democracy” against the forces of “authoritarianism.” For him, we are trying to serve our own interests as other countries serve theirs. If doing so causes democracy to flourish around the world, great. If it doesn’t, that’s none of our business. Cotton recently wrote a Wall Street Journal op-ed making the case for continuing to arm Ukraine, and he made clear that the justifications have little to do with principle and everything to do with self-interest. The Ukrainian “cause is sympathetic, but the world is a dangerous place and America shouldn’t act out of sympathy alone. We act to protect our vital national interests.” We should “back Ukraine to the hilt” because the alternative “favors Russia and harms our interests.”

Cotton does not dwell on the implications of his view that self-interest should trump morality and law, but it’s worth thinking about them, because he is right that similar thinking has long guided U.S. policy, whatever the noble rhetoric of our presidents. Cotton says the Vietnam War was worth fighting not because the Vietnamese deserved self-determination (about which he makes clear he does not care), but because “U.S. national security interests” were at stake, namely the question of whether Vietnam would be governed by a regime sympathetic to the U.S. or one sympathetic to our main geopolitical rival. For Cotton, the millions of Vietnamese people who died in the war might as well have been ants. Their lives simply do not factor into the equation. What mattered, as he says openly, was whether there was a pro-American regime or not. It doesn’t matter whether the majority of Vietnamese people wanted the South Vietnamese dictatorship gone. It was still legitimate to fight to preserve it, no matter the cost in lives or the opinions of the populace, because it was on our side.

Cotton does not mention some of the worst atrocities the U.S. has supported on reasoning similar to his own. For instance, when the Indonesian government started massacring communists by the hundreds of thousands in 1965 and 1966, the U.S. gave Indonesia its full support. The U.S. backed the Khmer Rouge after it was ousted by Vietnam, going so far as to oppose U.N. measures condemning the Cambodian genocide. When Saddam Hussein was gassing Iranians with chemical weapons, the U.S. not only continued to support Hussein, but concealed the evidence of Hussein’s crimes, because we wanted him to keep fighting Iran by any means necessary. All of this is appalling, but all of this is the perfectly rational consequence of adopting the Cotton worldview: ourselves above all others, morality be damned.

For the sake of both the rest of the world and ourselves, Cotton needs to be kept from attaining any more power than he already has. (It’s more than a little frustrating that the last time he came up for reelection, he didn’t even have a Democratic opponent.) It’s obvious enough why anyone in any other country should fear a politician with this worldview—Cotton might support an outright genocide if it served our “vital national security interests.” But Americans shouldn’t buy Cotton’s rhetoric about preserving their “security” and “safety.” Ripping up arms control agreements, violating international law, and viewing the rest of the world as enemies who need to be coerced does not ultimately make us safer. The Iraq War, for instance, was justified as a means of keeping the U.S. safe through deploying military force, but in fact it made the country substantially less safe by giving terrorists a powerful new recruiting tool. Blustering and confrontational rhetoric toward China makes an eventual war more rather than less likely. If the world ever experiences a catastrophic nuclear holocaust, it will be because politicians like Cotton believed other countries had to be threatened rather than negotiated with.

What is frightening is that, while Cotton is on the “hawkish” end of the U.S. foreign policy spectrum, his general views are not at all out of the mainstream. While he believes Democrats are weak and vacillating and do not sufficiently fund the military, the confrontational posture toward China, for instance, has been fully bipartisan. Barack Obama was not wrong when he said it “turns out I’m really good at killing people,” and both he and Biden pursued the Cotton strategy of embracing dictators who serve our interests. (Obama offered a historic $115 billion in weapons sales to Saudi Arabia, for instance.) Those who believe U.S. policy should be based on values rather than the pursuit of power for power’s sake might be horrified by some of Cotton’s rhetoric in the book, which sees the rest of the world as enemies to be subdued and openly advocates the embrace of authoritarian allies. But the major difference between Cotton and his Democratic opponents, despite what both he and they would say, is that he is more honest in his elevation of naked self-interest as a policy imperative. He might believe that Democrats erode the country’s power, they might believe that they support the “rules-based international order,” but the record of both Democratic and Republican administrations shows that the use of extreme violence to maintain American hegemony is a bipartisan constant. The belief that might makes right, and that the United States has a God-given right to be the most powerful country in the world, is foundational to U.S. foreign policy.