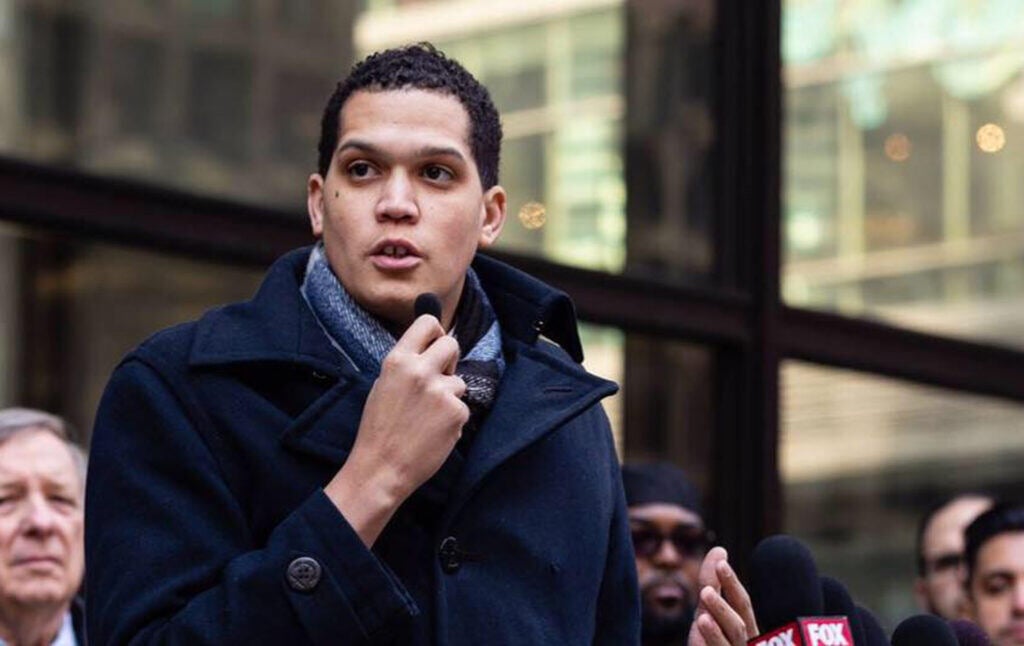

Meet The Democratic Socialist Holding Barack Obama’s Old State Senate Seat

In conversation with activist legislator Robert Peters about how leftists can operate “on the inside,” how to get your bills signed into law, and how leftists can adopt effective messaging on public safety and violence.

Robert Peters is a 36-year-old Illinois state senator who represents the state’s 13th district. It’s a seat that was held from 1997 to 2004 by none other than Barack Obama. But Robert Peters does not share Obama’s centrist politics. Peters is a member of the Democratic Socialists of America and a former delegate for Bernie Sanders. He has tried to steer a novel path, moving in mainstream Democratic party circles while grounding himself in movement politics. Peters was part of the Coalition to End Money Bond, which earlier this year successfully made Illinois the first state in the country to abolish cash bail. During his first year in office, Peters was the chief co-sponsor of 13 bills that were signed into law, including measures eliminating private detention centers, providing college students with SNAP benefits, increasing access to preventative HIV care for minors, increasing accountability for the foster care and corrections systems, and ending the Department of Corrections’ practice of suing ex-prisoners to recoup the costs of their imprisonment. He chairs the state senate’s Public Safety Committee and its Black Caucus. (Incidentally, he also turns out to be a paid subscriber of the Current Affairs podcast.) Peters recently spoke to Current Affairs editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson about his work on cash bail, how leftists can talk about violent crime without compromising on criminal punishment reform, and how he tries to “work within the system” while staying accountable to the left political movement. The interview has been condensed and edited lightly for grammar and clarity.

PETERS:

This isn’t a video, right? Because I just moved office and there’s no backdrop.

ROBINSON:

I wish it was video. Your shirt is fantastic.

PETERS:

My friend said I have the face of a 15 year old, but I have the shirt of a retiree.

ROBINSON:

Well, that’s cruel. I am very into colorful shirts. Now, let’s see, I’m going to introduce you: Current Affairs listeners, I am Nathan Robinson, editor of Current Affairs magazine. And I am here with Illinois state senator Robert Peters, who happens to be probably one of the only state legislators who subscribes to the Current Affairs podcast! And so it is such an honor to meet you, Senator.

PETERS:

Definitely. Thanks for having me. I’m a big fan of your guys’ work.

ROBINSON:

Am I right, you’re the only DSA person in the Illinois State Senate?

PETERS:

Yeah.

ROBINSON:

So that’s a landmark victory. And it’s been a hell of a journey to get where you are today. And I wondered if you could start by telling our listeners a little bit about yourself, and a little bit about how you ended up on the left.

PETERS:

Yeah, so my path here was a long path, I would say. So a little bit of my background: I was born during the War on Drugs during Reagan’s presidency. My biological mom was addicted to drugs. I was forced into adoption and I was born deaf, so hard of hearing or small-d deaf. I developed a speech impediment, had ADHD. You know, it wasn’t the easiest childhood physically. And then for much of my life, my adopted mom struggled with alcoholism. She struggled with mental health issues. We live in a world where you’re not supposed to talk about these things and you’re supposed to go through them on your own. And I was lucky enough to have a community that invited me into their home, a neighbor who had a door open. And so I grew up, was able to have surgery, which helped me with my hearing, developed the ability to speak with the speech pathologist. I still struggled with ADHD, still do struggle in that category, especially with anxiety. Over the last 30 to 40 years, we’ve told people to pick themselves up by bootstraps that just don’t exist. And for me, the best way we get through life is if we do it together, understanding that you have to treat each other as neighbors on this planet and look out for each other. That played a big role in my development.

I was raised in a very politically active Hyde Park in Chicago. My predecessor being the former president, Barack Obama, so Hyde Park has a history. Harold Washington lived in Hyde Park. It’s just very politically active. After the Great Recession, I couldn’t find a job. My mom, before she passed away, had 300,000 dollars of housing debt she shouldn’t have had. I was angry. I always knew I was angry about something. Why am I angry? And it was organizing, some organizers at the People’s Lobby that did a really good job of helping me find why I was angry. And I was angry at a system that clearly had failed my biological mom. It had failed my friends, my neighbors, my adopted mom. It failed my dad in many ways. My dad was a civil rights lawyer and a criminal defense attorney. He was always taking on the police for police violence. I mean, he’s the last line of defense for a lot of people. And it was a false promise that was always said to people. So many people being told that they’re going to get a thing that just never seems to come.

And I so went into organizing, I worked on a lot of campaigns. I worked in traditional Democratic politics. And then found my voice in terms of a left space and organized around that. And I helped start the End Money Bond coalition, fought to increase the minimum wage, fought to tax corporations and the wealthy. And then I was lucky enough to be appointed to be a state senator. And I was like, I kind of got a lot of work to do, and let’s do it. You know, let’s jump in. And that’s how I’ve gotten to where I am now. This is a long, long time, did I…?

ROBINSON:

Well, I did ask you for your entire life story. I do realize that the question was “Tell me everything that has happened to you up until now.” It was a very unfair way to begin. […] So I didn’t realize it was Obama’s old seat.

PETERS:

So my two predecessors are a former president and the current Attorney General of the state, Kwame Raoul. So I feel absolutely no expectations here. Yeah, the pressure’s off. I mean, it’s weird, I sort of thrive better that way. When you have ADHD and anxiety, sadly because of the way the world works, you develop a process where you feel like you’re always under pressure. In college, I would wait to write a paper until 10 o’clock the night before. And then I would just go at it and then it was maybe not the best grammatically written paper. But I think it was big work that helped me get through college.

ROBINSON:

Did you say you were appointed to office? How did that work?

PETERS:

So I have a close relationship with the county board president and the head of the Cook County Democratic Party, Toni Preckwinkle. […] I was able to get appointed by the Democratic committeeman when Kwame Raoul became attorney general. And some people ask me “How does that work?” And I would say, I don’t know if I can tell you that you can mimic my path to governing power. You know, I have two rounds of civil disobedience. I was a Bernie delegate twice, and I have a close relationship to Democratic Party politics. And I fundamentally believe the system is broken. I don’t know if I can say to somebody else you should do it exactly how I did it. I try to describe it to people and I say it takes a combination of things to get here, but one of them is luck. You know, after the Great Recession, I couldn’t find a job. And this is in 2009 and I worked in politics as an intern. And everyone was like, “Well, what a great decision, what great work you did.” I was like, nah, I was lucky. I worked for a candidate who was projected not to do well, who did an amazing job and then whooped everyone’s butt in the primary and that played a big role.

ROBINSON:

You must have a kind of complex relationship with Democratic Party politics, because obviously your politics… you’re a Sanders delegate, pretty far on the left, DSA member. And yet it seems like you’ve managed to maintain good relations or better relations than one might expect with people who are not as far to the left as you. I assume you struggle sometimes to decide the degree to which you need to act as an outsider and criticize the Democratic establishment and the degree to which you need to sort of work closely with it and be careful to cultivate good relations.

PETERS:

Yeah, it depends. It’s situational, you have to pick and choose. First of all, I don’t have enough organized power to pretend, nor do people pay enough attention to state senators—I hope we can get to a point that they do—just to fight for the stake of a fight. I fundamentally believe there needs to be a combination of things. Organized power: I organize on the inside. And you pick and choose when you’re going to do a battle on something. Because I don’t have enough energy or time to try to fight every battle. I mean, in all honesty, my hope is that more people get into office. And to be honest with you in the Senate, we’ve gotten more and more progressive people that makes it easier to do that.

And I am of the belief that power respects power. So I try to tie myself to the movement as much as possible because I am the conduit for their organized power and governing position. And they are the conduit for me being able to govern the way I want to. And if those are tied together, it makes it easier to get things done under the dome. I always think of the End Money Bond coalition. We’re the first state in the country to abolish cash bail. And a large part of being able to do that was the coalition flexed a good amount of outside power, understood that you do need to hire some people to work under the dome, to translate the language of the movement to people in the capitol.

ROBINSON:

Oh, I see what you mean, under the actual dome.

PETERS:

I would say there’s under the dome and outside the dome. Under the dome, you’re organizing and you have to constantly be in a state of building relationships and picking your battles and power mapping and all that stuff. And in the capitol that’s the way to do that. And then there’s outside as well. And you have to apply those same principles in both spaces.

ROBINSON:

I want to talk about the work you did on bail. Were there moments when you realized “Oh, you can actually win stuff if you organize well. You can actually change things”? For this series I’m interviewing left people who have reached government and who have accomplished things, to help get rid of that sense of hopelessness by talking to people who have fought hard fights and then actually noticed at a certain point that they had managed to accomplish at least some of what they wanted to accomplish. So do you recall whether there was a moment where you were like “Oh my God, we’re actually going to change the bail practices here”?

PETERS:

It’s funny because I am extremely competitive. And so when someone says something’s impossible, I’m like, “Okay, so you’re telling me I need to go ahead and try it.” And I think the people I organize and work with are pretty similar. Looking at that challenge, when we were first doing this, I did not feel it was the responsibility of us in the coalition to have to answer for the horrible lame talking points and excuses that you see from law enforcement. And what I mean by that is oftentimes you can feel hopelessness because you get defensive about your position. And I feel comfortable in my position. I feel comfortable about what we’re doing to build power and who I am, not to have to be defensive about what we’re doing. If we’re going to play this game about who’s got the right vision for the world, who cares about the safety of the world, I will put ours up against anybody.

I still feel a part of this coalition. We built an amazing coalition. I think it is a model coalition for the rest of the country. It has grassroots groups that are gonna mess you up with direct action. It has grassroots groups that are gonna work in elections. It has grassroots groups that work directly on policy. It has the policy org who understands their place is specifically on policy. It has communications to make sure it communicates broadly. I even recommended that we hire a lobbyist. I said “There’s do-gooder lobbyists in the capitol, let’s hire them,” and we brought in an amazing set of people who work inside the capitol. So combining all of that.

I think that for all of us, yes, we were nervous, anxious, and thought, “This is just going to take forever to get done.” But we were so committed to making this happen. And the coalition is such a model to the point where the lead public defender of Cook County comes from the coalition, Sharone Mitchell, and they’ve gotten me into becoming a state senator—I always say I come from the coalition. And the two of us are doing amazing work in governing power because of this coalition.

And I think, yes, there’s anxiety and there’s fear. But if you believe your vision is the right vision and you care, and you’re willing to evolve—that’s important, because if you believe your message and tactic are always going to be the right one and you’re not listening to people and you’re not growing, I don’t think you really have a path to win anything or win power. If you look at the End Money Bond coalition, [for example,] to this day they talk about public safety. Before it was just like “money bond is wrong, it’s the worst thing ever, we’ve got to end money bond,” but that’s a negative statement not a positive one. And so they say “End money bond because it’s not actually keeping people safe. Here’s what we want to see for safety.” And describing that sense of safety for people. And that only happened because after being attacked over and over again, [we thought] “Why are we ceding ground on our vision? We know that what we’re doing is right.” And as we’ve talked to people we’ve evolved and grown, and we continue to build on that coalition.

ROBINSON:

This is all really fascinating because, as I say, I would like to try to figure out things that other leftists could learn, and this is all stuff that [offers lessons.] You brought up speaking about public safety. I feel like there is a challenge right now for those of us who are horrified by the criminal punishment system. There’s been this spike in violence, and I sense this effort to roll back some of the advances that we made in creating a consensus about reforming that system. And we really want to avoid lapsing back into the “tough on crime” stuff that built the mass incarceration system. So I assume you have had to think about how to talk to ordinary people who might feel afraid of violent crime, and how to pair a reassurance about people’s safety with maintaining your commitment to ensuring that more people aren’t thrown into this really horrifying criminal punishment system.

PETERS:

My belief is that if people want to doubt that I care about being safe, when I walk down the street I live in a place where there’s violence. That violence is not an indictment on criminal justice reform or whatever you want to call it. That violence is an indictment on a status quo that for the last 30 to 40 years has failed to keep us safe, has been filled with false promises. And it’s because it’s built on cowardice from people in political power who don’t want to make the hard decisions about the fact that if you build more housing and keep schools open and you give people healthcare and you fund it at the local and state level by taxing the rich, you’re more likely to keep people safe. So in every effort, instead of having to do that, they said “We’ll just throw a hammer at it called criminalization.” So my favorite thing to do to people who say that they care about public safety through criminalization is to say “Okay, then what?” So let’s say someone says “These damn kids are committing violence”—and you see these academic types on Twitter who think they know what they’re talking about, spouting off hot takes about bullshit. It’s very clear. The answers are very simple. And if you talk to anybody—for me, who knocks doors and does meetings, I think I know more about what public safety wants, combined with the data that shows it.

So here’s what we do. You pick up a kid and you’re like “This kid’s a shooter. And what we’re going to do is we’re going to hold this kid and we’re going find out what their parent is doing, because obviously the parents have failed.” And then I just go like this: “And then what?” Because you know what, it ain’t going to do shit to keep people safe. The very idea that we’re going to invest all this money that isn’t stopping murder, isn’t solving murder, and isn’t keeping us safe. And so I would say that the work that many of us are doing to fundamentally transform our system of safety is rooted in keeping people safe. We know what safety looks like. If you live in the North Shore of Chicago, where there’s a lot of money, you’ve got a good school. You’ve got a good job. You’ve got good public transportation. You have food on your table. You have good housing. That is public safety. If you’re not giving people that, you’re giving people a false promise. So almost everything I message with what I’m doing is that I’m not going to cede the ground from my office or when I organize when it comes to public safety.

ROBINSON:

Because when they say, “Okay, yes, you talk about bail reform, but how are you going to make sure that my house isn’t broken into? How are you going to make sure that I don’t get carjacked?” you have an answer of what real public safety looks like and the kinds of investments it’s going to take and what’s going to get you there. And people can hear it and go “Oh, okay, he cares about my wellbeing.”

PETERS:

And it gets even better. Bail is about who gets locked up and who doesn’t, based off money. So anybody who makes an argument, any official who says “if we get rid of bail, we’re going to make us unsafe,” I’m like “No, you’re saying it’s okay for someone like Kyle Rittenhouse to be let out. But it’s not okay for a poor Black person to be let out because technically our bail system is based off whether you have money.” If you have wealth and money, you can do whatever you want if you get bail, because then you can just get out. So I say to someone “When you take that young person who’s broken into your place, and you think we need to throw every bit of the hammer at it it’s not going to stop.” It won’t stop. What you are afraid of won’t stop. If we want it to stop, we have to invest in each other, in our sense of community, our collective self, the society. That’s where we’re going to be able to stop this. And if you think that someone who committed very bad things and has money should be out, then that’s what you’re talking about with bond. You’re talking about a tiered system that says if you’re rich and wealthy, and particularly if you’re white, you get to be able to pay yourself out to go back into the world, and that has nothing to do with public safety, it has everything to do with race, class, and gender.”

I would say the best way to put this is that fundamentally anything that’s happening right now when it comes to crime and violence is not an indictment of criminal justice reform. It’s an indictment on the status quo. And I think everyone needs to remember that if somebody’s complaining, like losing it on Twitter, saying “we gotta stop talking about this, it’s bad electoral politics: (A) It’s bad electoral politics. And (B) what they’re complaining about is things we do now, not things we are planning or hoping to do.

ROBINSON:

Right. You’re attributing it to something that hasn’t actually happened, that we haven’t actually got. […] How do you talk to people about police budgets? If a constituent comes to you and says “I hear all this stuff about the left wanting to defund the police, they want to abolish the police. You can’t get rid of the police!” What do you say to someone who says that to you?

PETERS:

I just keep it pretty straightforward: it’s not my job to figure out the clearance rates on murder, but it is the job of the public safety department. If they say they’re going to stop murder and solve murder, they should do it. We have harsher treatment for our education system than we do for our systems of safety. And so if we’re going to spend billions of dollars not to do the thing that it’s supposed to do, then they better explain that to the public. But that’s not my job to explain it for them. So if people are like “Wow, this crime is out of control,” well, we’re spending all this money, what’s going on here? Why is it that you’re not stopping and solving it? And it’s important to note that people don’t realize this. […] I think that it’s not my job to have to defend the status quo for a horrible record on criminal and violent activity.

ROBINSON:

[I want to go back to what you were saying about the End Money Bond coalition], and why this coalition was a model coalition that you thought others could emulate. What I got from what you said so far was: you talk about adapting and being willing to learn, and making sure that when you figure out what people need, they hear a message that addresses whatever public safety concern they have. You incorporate and address that and the messaging gets better. You also talked about how the different parts of the coalition each had their particular job and they were really good at it and it worked together. Are there any other lessons from the success of this coalition, why you think it works well as a model?

PETERS:

Yeah. I’ll use the fact that the public defender comes out of this coalition and I come out of the coalition and that is clearly understanding the importance of governing power and why you need governing power and why you need to respect it. So “inside outside” is always thrown around, and it gets misused. You can fundamentally change stuff with a good inside-outside strategy, if everyone can respect each other and respect certain positions of power and understand power and the role it plays in this world.

ROBINSON:

Maybe you could lay out for our listeners who aren’t necessarily familiar with Illinois state politics what some of the most important pressing issues in Illinois government have been during your time there that you’ve been working on. I realize I am opening a can of worms.

PETERS:

There are a host of things. We’re in a big battle to pass a clean energy bill, one that includes ambitious timelines for decarbonization. Hopefully we can get that done by the time this podcast drops. Gov. Pritzker. Hopefully we can get that done by the time this podcast drops. Listeners should google that. And then the budget: Gov. Pritzker closed three corporate tax loopholes and we were able to improve our bond rating. And I know bond ratings are problematic, but it is the world that we live in and it has made our state healthier. During my time here, we’ve increased the minimum wage to $15 an hour. Of course, we’re a triple-D state, so I have to emphasize that, because there’s not a lot of them in the United States.

ROBINSON:

Meaning Democrats control both houses and the governorship.

PETERS:

Yes. And that’s not always been the case and it creates this tension. I work well with my colleagues in the Senate. Well, there’ll be times when we disagree, but there are also times where we actually find some common ground issue by issue. And I know the importance of that, and it can create fundamental change. I mean, just to give you an idea of bills I was able to carry on behalf of so many organizations, we’re going to be the first state to abolish cash bail. We’re going to be the first state with mental health first responders. We banned private detention centers for immigrants. And that was just me. There are literally people who’ve carried so many. Senator Omar Aquino passed a bill that basically prevented ICE from operating in county jails. Part of that is that when you have a supermajority—and you’ve got to protect that supermajority—some people who otherwise in their district might not be the safest bet for them to make these votes, you could play around with the roll call more often to be able to get the 30 votes, which how much you need in the Senate. And so having the ability to play with the roll call makes it easier for us to pass some legislation.

ROBINSON:

Sorry, what does that mean, “play with the roll call”?

PETERS:

Right now we have 41 out of, I believe, it’s 59 senators. 41 are Democrats. You need 30 to pass a bill. […] I will always say that I generally have about 27, 28 votes that I can rely on, generally. And I go around on every vote. I have a binder and in the binder I have a roll call sheet. I have fact sheets. I have the bill language. And so I was able to pass I think 17 bills this year, and a large part of that is I went around with my binder to everyone’s desk, every one of my colleagues. And I talked to them about the legislation. Everyone. Not only did I do that, if there was someone who was quote unquote a “moderate” Republican, I still talked to them. I said, “You know what, it’s your job to answer the question that I’m throwing at you. It’s not my job to answer it for you.” So I’m going to go up to you with my binder. And I’m going to ask you. One of the things that stands out to me: me and senator Terri Bryant, she’s a pretty right-wing Southern Illinois Republican. She has four prisons in her district. We generally don’t agree on anything. But we had a conversation about, I can’t remember what bill it was. And she said she supported it. And then she got on the floor and she praised me, the most left person in the Senate.

And my colleagues who are a little bit more moderate, they were like, “Robert, can you believe, Robert?” I said, “You know what? I just went around. I asked a question, she agreed, and we were able to move it.” Now, I don’t know if I should be saying this out loud, because I’m sure this could be used against Terri Bryant. And that would be a horrible thing. I don’t want to be someone’s negative attack ad. But the idea is being able to have those conversations.

ROBINSON:

I think Bernie does a similar thing. I feel like there are some Republicans who are softer on Bernie than you might think, because he’s very, very pragmatic in trying to find the narrow, narrow spot of common ground and work with it.

PETERS:

There’s so much nuance to Senator Bernie Sanders that gets lost. And part of the reason why I go talk to some colleagues on the other side of the aisle is because of the work that Bernie did with Senator McCain over the veterans affairs work. And I remember that story and I was like, “Well, look at that, that’s Bernie Sanders, literally working with John McCain on a piece of legislation.” And to me, again, I come from organizing. Who is it to me? Always have a conversation with someone. Always have a good ask for someone. You don’t need to be transactional, you just need to sit down and get to know them, and have the conversation with them. And maybe in some cases you might be able to get their vote on a piece of legislation. And that’s why I carry that binder with a giant roll call sheet, because I want to know my yeses, my nos, and my maybes. And if someone’s a maybe I want to talk them through it.

I don’t try to introduce my own bills. I try to have people from organizations to help carry the bill. So you have an outside and inside strategy. So almost every piece of legislation I carry is because some organizations have presented me the bill, and it fits my vision, or we worked on it together. And then we say “Okay, let’s work together on this.” I’m going to do my inside-outside. And there’s times when I go “Look, I’m running to a roadblock here on the floor, I need you to go have a conversation and lobby so-and-so, so if you could do a lobby day here’s the four people you need to talk to.” And then a colleague will say “I had a conversation with someone who is directly impacted by such and such thing. I’m intrigued, I’m open to it. Talk to me about what you’re doing.” And we have those conversations, and then either they move into a green, which is a yes, or they move into a red, which is a no. And there are colleagues who don’t tell me their vote and I’m like “Just tell me, so I know it’s on my roll call and then I don’t need to worry about it anymore.” You know, I’d rather have someone tell me a no than to wait until voting time on the floor to press a button. That’s not helpful, to walk from their desks, you know? I’m a big believer in the power of the roll call. I think if you’re not doing strong roll calls and you’re not doing structured relationship building, yeah.

ROBINSON:

Many people who have lefty politics might be cynical about the way that state government works. And they might assume that essentially votes are all predetermined. People are gonna vote the way they’re going to vote. I see you shaking your head, but I’m just laying out the way that I think if you’re a cynic about politics, you might think. There are these politicians that go in, they have these interests, they have these ideologies, they have these corporate backers and essentially, to negotiate and work relationships with them would seem futile. But actually what you suggested is that you can actually get a lot done if you focus, you can work with people who don’t share your ideology.

PETERS:

Yeah. Look, it’s not going to work every time. There are some things harder than others. But you better go hard at a roll call. And I think people are mythologizing, especially with the Democratic Party as like this big behemoth with complete and total control. No, it’s actually a very open and empty space for people to fill. So go fill it. We can fill it. Honestly, some of the most progressive legislators in Springfield were appointed by Democratic Party committeemen. So because we’re in a period of crisis, it’s important to note that we can either use it as an opportunity to do a lot of great work, or we can not.

And it’s important not to make assumptions, right? If you make an assumption or you just completely give up in the fight, well, then, yes, nothing’s going to happen. And that type of pessimism in a lefty space is not helpful. I think that at the end of the day, what matters most is: you’ve got to get your own people in office, it’s important, you’ve got to be tied to a movement, and you’ve got to be committed. If you’re going to go in that space, you’ve got to get your own people and that in office, it’s important, you’ve gotta be tied to movement and you’ve gotta be committed. If you’re going to go in that space, you gotta roll call. I can’t stress that enough.

ROBINSON:

The oldest story in politics is the story of the idealist who goes into politics and then makes one small compromise and then makes another compromise. And then sooner or later becomes everything they went into politics to oppose. I assume that you have thought about that as you’ve gone “under the dome,” in terms of making sure that you stay committed to your core values. How do you think about how you can avoid making compromises that are a bridge too far? How do you make sure that you stay principled and committed to your original values?

PETERS:

It’s a few things. I try to talk to and relate to the base as much as possible, particularly when I’m in Springfield. I believe that my office should be a conduit for organizing, for movement spaces. So basically opening it up, whether it’s mutual aid efforts on the South Side, it’s hosting meetings, it’s being part of meetings. And sometimes when I’m not able to get something done, being held accountable. I try to make sure that I’m tied as much as possible. And I will ask. When he passed the bill, the safety act that had our end money bond piece in it, at two o’clock or one o’clock in the morning, I was talking to the coalition about negotiations on this bill. I said “They’re trying to do this in the bill, and I need to know: how far am I allowed to go?” This is how it normally goes: I remember saying to my colleague on the floor—usually people say this to you when you’re the progressive, so it was great to sort of return the favor so they can hear how sounds because it sucks—I said: “My people won’t let me go any further. That’s it. I can’t negotiate any further.” We’re not as weak as people think.

So when I’m negotiating on something, I always say: “Have you talked to the coalition? Have we talked to the organization, have we talked these folks in this movement?” Because I can’t say yes to that without approval. And the other part about this is I intentionally try to take on more and more risks. And what I mean by that is before electoral and legislative decisions that I make, I ask myself: does it scare the shit out of me? If I do this, am I going to be screwed by people on the right?” And I say to myself “Okay I’m going to make this decision and then we’d better build some real power.” Like, all right, got to organize.

Me and another state rep on the North Side, she’s sort of been a mentor on some stuff, she told me about a bill she wants to do that’s a huge fight for the left. And I’m not going to name it yet, because I don’t think we’re ready there, but it is a big one in the decriminalization space, and that’s all I’m gonna say. And I remember being like, “Yeah, I’m all in to do this, but holy shit.” We’ve got to really organize a crew to make this happen.

Being a DSA member was something where I said, it’s going to be bold, and there are people who have feeling about this and it’s a complicated district that stretches all the way to the Indiana border. And I think I need to show people this is who I am and I need to keep building with a long movement to build more power.

My hope is that at some point there should be enough people like myself in governing power for me to move on. My dad died when he was 63. And I always say that I want to be, like, a professor, want to be retired out of this by that point in an ideal world. And If I have kids I want to spend my time with them because I spent a lot of time with my dad and then I was 26 and he was gone. And so that plays such a big role in my thinking.

ROBINSON:

So my final question for you, Senator Robert Peters, would be what’s next? What’s on the agenda now?

PETERS:

So there’s a few bills. Some that I want to talk about publicly and some I don’t, because I want to make sure that before I introduce or work on a piece of legislation with folks that we’re in the right place and we’re ready to build on it. But there were some things I wasn’t able to get done this year that left me very disappointed. One of them is the name change bill. Particularly transgender folks who were incarcerated being unable to change their names in the public record, and often times they’re left with their dead name and it causes so many problems and so much pain and trauma for folks, so I want to make sure make people aren’t having to be re-traumatized with a dead name, so they can go buy a house, or if they’ve had a divorce, they don’t have to have that linger. So we’re going to keep pushing on this.

Either to end solitary confinement or get as close as we can to ending solitary confinement. There’s this guy Anthony Gay, he was incarcerated in solitary confinement, he hurt himself so he could be out of solitary and see the sun. I think that’s something we can move from, and I’m hopeful we can get that done, but it’s going to be tough work. I’ve talked to Anthony, to organizers, and we’re just going to have to really convince people that this doesn’t do anything to help people who are incarcerated.

The other one is protecting the end of cash bond. I know with the fact that there has been a heightened level of violence, those that represent the status quo are going to make up whatever excuse they need to to continue the incarceration machine. They’re going to try to roll back what Illinois did. I’m committed to fight them tooth and nail to prevent that from happening.

I have a couple more bills I hope to get signed. The governor signed a few of my bills, but two more I’m hoping to finally make it. One makes it officially a law to have non-police first responders to mental health and behavioral health issues, so that those who are going through a traumatic event are met with someone who’s a behavioral health expert to help them without the police. You hear about this on the news, it’s passed as a law in the state of Illinois, anybody who wants that bill reach out to Access Living. It’s a transformative program. It goes into effect in 2023, hopefully that gets signed.

The other one is mandatory school play time: every kid has to have 30 minutes of unstructured playtime in every public school in the state of Illinois.

ROBINSON:

It’s so nice to hear about all this. I think there’s a lot that’s very valuable here and very encouraging in a time when people feel pretty despondent, like nothing can happen. Like the forces of the status quo are impenetrable and unmovable. And I think [you’ve shown] it’s very difficult, but you can make some progress slowly. So senator Robert Peters, thank you so much for joining me on Current Affairs.

PETERS:

Definitely. Thanks, Nathan.