How to Destroy a Story

10 years after the launch of Game of Thrones, Samuel Miller McDonald looks back at its promising start—and how it all went wrong.

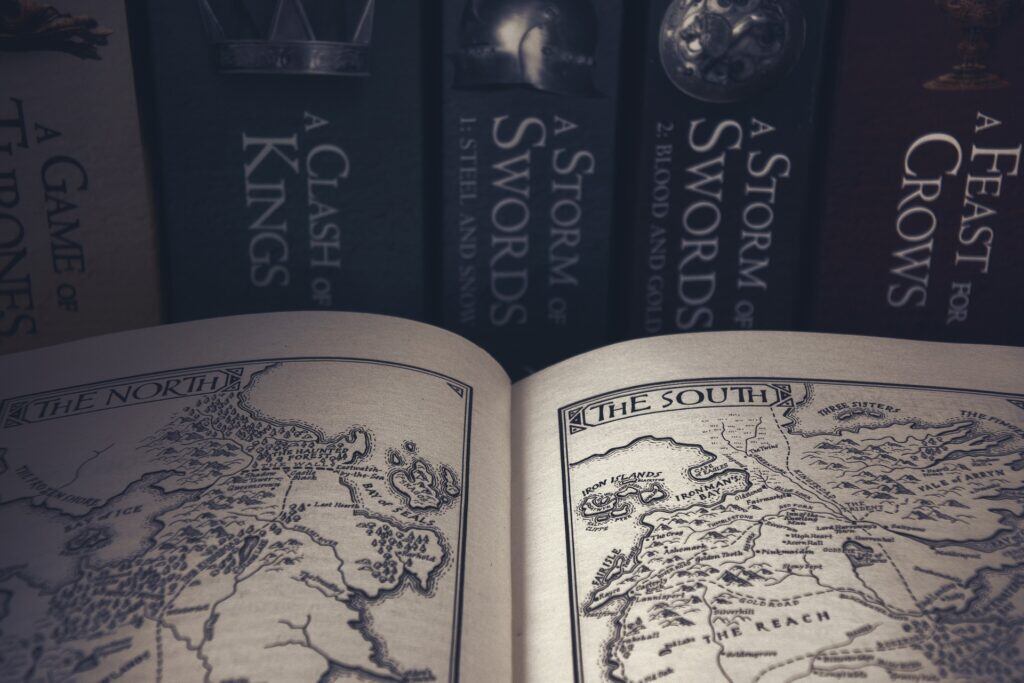

Sometime in the early 2000s, when it was still just three books, I read George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire for the first time. Being a brooding, lonely teenager living in Northern Michigan’s wintry hinterland with a fantasy about joining the Night’s Watch against the coming climate threat, the series really spoke to me. So when HBO announced they were adapting it for television, I was thrilled, and remained thrilled for eight years. What luck: not only was this slick big-budget production well-written and crafted—with exceptional plotting, acting, cinematics, and music—it stayed faithful to the spirit of the story I adored. The show—which ran from 2011 to 2019—has reached the 10-year anniversary of its first airing, and to celebrate this “Iron Anniversary,” HBO is launching a month of new content, including a $2.2 million Fabergé egg. I won’t be consuming any of this content, let alone the egg, because, as many fans agree, the finale killed the story and much of the enthusiasm that would have lingered after it ended. While it was running, Game of Thrones inspired serious scholarly research, dominated public discourse, compelled politicians to generate pandering commentary, and spawned countless memes. It was loved by both the public and critics, a rare combination that typically indicates that a narrative work will remain an essential part of the canon into the future. But then suddenly—after some excellent post-mortems—it vanished. Instead of paeans to the show celebrating its new place in entertainment history, most analyses picked apart its catastrophic fall from relevance.

Sure, the final seasons simply declined in quality. The dialogue curdled to cringe banter, like the frequent instances of Tyrion, erstwhile defender of “broken men,” making bad dick jokes at the eunuch Varys. There was that cameo from gaudy song gnome Ed Sheeran. (Westeros meets strip mall!) There was the jarring collapse of time and space: vast expanses of hundreds of miles and weeks or months (no one knows!) were crossed in a single scene cut. Events that should have sprawled over whole seasons were compressed into eighty-two minutes. “The Long Night,” it turns out, didn’t refer metaphorically to climate change and to years of darkness and cold lasting a whole generation, but one single night. As in, “man that was a long night,” you might say after a gruelling late shift. The pacing that had been so crisp suddenly shuffled like a wight (a deteriorating corpse reanimated by the show’s enigmatic ice demons).

Some characters’ arcs were given moving culminations, tragic or triumphant, but, as Aaron Bady argues in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Game of Thrones failed colossally to deliver a good climax after a near-decade of buildup. For many years and seasons, we had been led to believe that the Long Night and the White Walkers represented an existential threat, that there were gods or God breathing ascendant magic into the world, re-enchanting what had recently been a more secular world, that the heroic Jon Snow had a secret identity which was important, that Daenerys was a righteous emancipator, that the mysterious Bran had some mystical role not just in this time but through the ages, tapping into a divine temporality. But in the end, none of that seemed to matter. The White Walkers turned out to be much less of an existential threat, as they were easily destroyed not by magic or dragons or global solidarity, but with a knife and some comic book antics. The fabled terrible winter didn’t even reach beyond House Stark’s ancestral fortress, Winterfell (did the writers take the name of the castle too literally?). Jon Snow did have a secret identity, and Bran did have mystical powers, but neither mattered when it came to the ending. Daenerys, meanwhile, mostly did follow her character’s arc, but not in a way that sustained its original narrative logic. All the magic that was starting to seep back into the world suddenly vanished for no apparent reason. A good climax should have, in Bady’s words, “taken you by surprise in the moment, but as it sank in, you would have realized how it had been earned by what came before; and after the show was over, you’d have been satisfied by what it all added up to and meant.” That is, it should have meaningfully followed the internal logic created by the story. To plunge with the speed of a speared dragon into cold cultural irrelevance requires something more than an epic slip in writing quality or a fumbled climax and bungled denouement. After all, the final seasons did not just get worse; they, and the finale in particular, invalidated much of what came before. To enjoy rewatching the show today entails an exercise in forgetting what you know is coming. To destroy a story so thoroughly required the writers to not just get sloppy, but that they actively violate the spirit of the tale.

One quality that made Game of Thrones unique among modern political stories was that it took the materiality of politics seriously. In West Wing and Veep-style shows, discourse and arguments dominate. The force that moves politics is individuals navigating institutions, talking to each other cleverly, and winning the debate. Power is distributed by opinion polls and imagined electorates, speeches and slips of the tongue. This analysis of society is idealist, rather than materialist: the beliefs and ideas of people matter more than the geographic and material contexts in which they occur. A Marxian materialist form of storytelling would emphasize the role of physical realities in shaping politics; idealist storytelling emphasizes the role of individual minds and decisions. While Thrones, too, moved much of its plot with the Walk-and-Talk (what Tyrion describes as “great conversations in elegant rooms”), it also took very seriously material realities as engines of power. The North is nearly unconquerable because of its vast snowy miles, giving the Northerners leverage in King’s Landing; the Iron Islands are spits of rock with little arable land—the Greyjoy motto should be We Cannot Sow—leading to a culture of raiding and pillaging on the coasts and mostly marginalization elsewhere. The Tyrells are powerful because of their vast agricultural resources, the Lannisters because of their gold mines, and the Targaryen dynasty—of course—because of its dragons. The Free Folk beyond the wall subsist on a foraging mode of production, and so their societies are realistically less hierarchical, less dense, and more nomadic. The ice zombie White Walkers derive much of their power not from their correct arguments (investigation of their motivations is mostly left out, in one of the show’s greatest failures), but rather from their invulnerability to worldly obstacles like weapons, wealth, and food. All of these material factors play important roles in the exercise of power throughout much of the show. When the clever influencer Petyr Baelish proclaims, “Knowledge is power,” queen-mother Cersei Lannister rebuts with, “Power is power,” while threatening to order her guards to cut his throat (what she means is, “control of wealth, resources, and the violence of the state is power.”)

This isn’t to say, of course, that Game of Thrones is a Marxist parable in any sense. Its analysis of class conflict rarely gets much more sophisticated than suggesting that lords mistreat peasants, the latter of whom only have a few minutes of collective screentime in the show’s seventy hours. The only time we see members of the lower classes is when they’ve moved up into the institutions important to the show’s political dynamics, becoming men of the Night’s Watch, Sparrows (a militant gang of theocrats), or promoted to knights and lords. Even so, the show remains distinct among political series for its material politics, and there are several nods to the violent origins of property enclosure.

In the final episode, however, all such material realities fell away as we’re taught, with pedantic, self-aggrandizing condescension, that “power is…stories.” “There is nothing in the world,” says Tyrion, who has otherwise been the brain of the story, “more powerful than a good story.” It is hilarious that a story propounds the great power of stories while simultaneously surrendering all the power it had previously exercised as one of the world’s most popular stories by suddenly modeling fatally bad storytelling. Yes, it’s true: good stories can be powerful. But so are geography and materiality, and the story, in the end, failed to take them seriously. Winter didn’t come after all, despite earlier claims that a long summer (lasting, in Westeros, for several years) must lead to an even longer winter. The threatened food shortages never materialized, the dragons didn’t yield a millennial dynasty, the vast wealth of the Iron Bank—and its power to threaten nations by leveraging debt—simply, in the end, didn’t matter.

In one of the strongest post-finale analyses, Zeynep Tufekci argues that the show destroyed its own legacy not just because the finale failed to live up to the original narrative, but because it abruptly changed narrative lanes entirely. Most of the series had been “sociological storytelling,” in Tufekci’s words, rather than “psychological storytelling.” That is, the show was more concerned with institutions and big-picture structural politics than the individual psychological dynamics of the characters. Most big-budget Hollywood storytelling is driven by the individual decisions of characters, which typically means we end up with a boring dichotomy of heroes versus villains, or major plot turns that depend on an individual’s personal morality and decisions. For most of its run, Game of Thrones was telling a sociological story in which characters display complex motivations that are shaped by their circumstances and surroundings, yielding more interesting and realistic problems and dynamics. More importantly, this complex storytelling equips viewers with the tools to more readily respond to contemporary political challenges, which tend not to be driven solely by the particular psychologies of the actors involved, but also by the structural conditions of the systems and institutions through which politics happen. “Arguably, the dominance of the psychological and hero/antihero narrative,” writes Tufekci, “is also the reason we are having such a difficult time dealing with the current historic technology transition.” It was when the show began to move past the sociological material in A Song of Ice and Fire—which Martin has tragically failed to complete, leaving the showrunners to use vague story outlines to write beyond the books—that it began to transition to psychological storytelling and that the quality began to go downhill.

Good climate change fiction involves, in a sense, a combination of both material and sociological storytelling: climate change is, after all, geographic materiality impacting the structural, institutional challenges of politics (and vice versa). The weather, and the winter that was supposed to annihilate all life, may have been the show’s most relevant feature, and the showrunners’ bungling of it marks their biggest betrayal of the story’s spirit. While George R. R. Martin may or may not have started with the White-Walkers-as-climate-change metaphor in mind in the early 1990s, he has since endorsed the idea. And the show seemed to run with it, featuring Jon Snow scolding the squabbling lords for playing their power games rather than confronting the existential climate threat coming for all of them, sounding much like an exasperated Greta Thunberg (just months before Thunberg would actually attend a U.N. meeting to do this in the real world). The show’s White Walker origin story (so far a departure from Martin’s series, which has yet to reveal their origin), can also be read as a climate metaphor. In the show, the indigenous Westerosi—the non-human Children of the Forest—stick a black rock into the heart of one of the first humans to arrive on the continent, creating the Walkers as a weapon to defend against the other humans who are brutally colonizing Westeros, killing the Children, and cutting down their sacred trees. Climate change, too, can be understood as a direct result of colonial imperialism, which in its later years was powered by climate-wrecking fossil-fuels that still play a central role in maintaining global colonial relations. While the show indefensibly places responsibility on the indigenous Children for creating the monstrous White Walkers—real-life Indigenous people are the people least responsible for climate change—the Children at least have a good reason for doing so. There’s a degree of fairness when the descendents of colonizers are invaded by monsters in their turn; they are simply reaping what they’ve sown. (If the story had ended in the triumph of winter and the White Walkers, it would have in many ways been more honest.)

Even in the beginning of the final season, as the show slides into silliness, it nods self-consciously at climate change. Tyrion, in a conversation with Jon Snow, suggests that the problem posed by the White Walkers is simply too big to motivate people. “People’s minds aren’t made for problems that large,” he says. “White Walkers, the Night King, Army of the Dead, it’s almost a relief to confront a comfortable, familiar monster like my sister [Cersei].” This doesn’t quite make sense in the world of the story: the White Walkers, after all, aren’t too big or too complex a problem. You might say that they’re a strange, unbelievable problem, being mythical monsters leaping out from children’s stories, but not too big—the Army of the Dead isn’t much bigger than the combined armies of Westeros, after all. It’s not their scale or complexity that’s difficult to understand or to be motivated by—quite the opposite: the scale of the advancing Dead seems to be the biggest motivator when it comes to the living uniting forces and defeating them. It makes sense for Tyrion to say such a thing only if he were making a conscious, metatextual nod to climate discourse, in which climate change is very frequently considered too big and complex to serve as a motivating force for change.

It would have been a great public service for such a popular show to take climate change seriously and shape its narrative around confronting it. After all, there is a dearth of good climate fiction. But again, this is where the ending failed. The great threat of the White Walkers, building since the very first scene of the first episode, was easily solved in a single night when a fierce young woman stabs the zombie king with a dagger. (Somebody give Greta a knife, I guess?) With this one stab, the show ceases to be relevant—or creative—in the most important way imaginable. By falling back on the cliched fantasy trope of “just kill the bad guy,” the show shrugs off real problems, refusing to reflect our own plight with any dignity or seriousness. It kicks its viewers out of the meager shelter of comfort, inspiration, and imagination that art can provide. Good luck stabbing climate change to death, peasants, the showrunners seemed to say. We’ll take our mountains of money and move south.

With the climate crisis safely stabbed to death, the final episode culminates with a self-congratulatory “election” by Westeros’s most powerful lords at a board meeting. This episode, like many others, was written and directed by the showrunners D.B. Weiss and David Benioff, the latter of whom is the son of Stephen Friedman, also known as the former chief of Goldman Sachs, former head of the New York Federal Reserve Bank during the Great Recession, and Chair of the U.S. President’s Intelligence Advisory Board under Bush and Obama. The limits of liberal imaginations are revealed with a conclusion that suggests the most desirable outcome is a technocratic best-and-brightest committee chaired by a supernatural king. Power is bad, Game of Thrones tells us, power corrupts, it enables the worst impulses, achieves the worst outcomes…unless it is exercised and controlled by a board of deferential wunderwonks. And here, the shift from materialist to idealist, sociological to psychological, is complete. Bran, the new king, has the ability to “see” the past, which has a sinister implication entirely unacknowledged in the show: his word will be taken as a purely true record of the past with no possibility of verification, while his ability to see through the eyes of other creatures presents a startlingly dystopian surveillance capability as a positive development. The idea that, in reality, there could be a perfectly true account of history or a benevolent panopticon is as dangerous as it is foolish. It’s true that the disabled Bran “the Broken” cannot procreate and install a hereditary dynasty, but the lords themselves—the wonks who elect the monarch—will still maintain hereditary and unaccountable power. A show like Game of Thrones that begins with a critique of unaccountable hereditary power and ends with an uncritical celebration of unaccountable hereditary power is a show that respects neither its viewers nor itself.

As Drew Daniel points out in n+1, the ideology on display in the finale goes little beyond a “sophomoric” embrace of liberal horseshoe theory, falling into “a familiar developmental story about political maturity as an inevitable process of rightwards drift from youthful leftist enthusiasm toward the mellowing complacency of centrist middle age.” Power, in this view, is best expressed by the “chummy…proceduralism” of a Board of Trustees. Any leader who tries to free too many people too quickly—as we see in Daenerys’ turn from Breaker of Chains to mass murderer—will inevitably end up a bloodthirsty tyrant. It’s no longer suggested that power corrupts, but only that power in service to a righteous cause corrupts. Tyrion suggests that a leader who believes they’re doing good will be able to justify any atrocity, apparently forgetting about all the atrocities committed for more selfish reasons over the past seventy hours of story. The lords, meanwhile, laugh off Sam Tarley’s suggestion of direct democracy and broad accountability, which is odd, because these concepts are not narratively ridiculous in Westeros—the Night’s Watch, the Free Folk, and Ironborn all practice forms of elected representation. Someone else is laughing off democracy here, and it may be Benioff and Weiss themselves. To take Martin’s unfinished story, with its critique of unaccountable power, and clumsily attach to its end a message of deference to unaccountable power is, in Daniel’s words, to “disarm and defang and polish” Martin’s work on behalf of a massive, powerful media corporation whose board of directors would have good reason to prefer the Benioff/Weiss ending.

But perhaps more egregious even than this cringy, faux-adult bureaucracy muddling my nice dragon show is its apparently sincere devotion to capital “p” Progress. In place of a vaguely Marxian materialist historiography of class exploitation, the end suddenly pivots to a Whig historiography that views the increased freedom of lords from monarchs as evidence of gradual, inevitable political progress. Not only are we treated to a glimpse of the birth pangs of some kind of proto-Magna Carta and the first flame-licked bricks on the road to (what in the U.S. and Europe passes for) Democracy, but we get a glimpse of the forthcoming Age of Reason and stirrings of Enlightenment with the highly literate Council of Smart Guys returning to their supremacy in a de-enchanted world. We even get a hint of the burgeoning Age of Discovery with prodigy assassin Arya’s aim to explore “whatever’s west of Westeros.” Will she be bringing markets and smallpox with her? (The wonks likely hope so.) The North, meanwhile, will be ruled by newly ruthless girlboss Sansa Stark, who literally said in the final season that she was glad to have been brutally raped because it made her into a mature, successful Machiavellian political actor. Some women, the finale seems to suggest, are required to suffer the worst torment to deserve such progress. Daenerys, who also suffered spousal rape, just went too far in her desire for power and jumped the queue (unlike Sansa, she didn’t ask a king for permission to rule her own land). It seems that from the lords electing an omniscient and incorruptible king, it’ll be just one small step to the beautiful utopian liberal democracy we live within today, where sons of millionaire financiers can become millionaires themselves by simply creating—and, most importantly, destroying—beloved art.

Not only do the showrunners appear to really believe the liberal Progressive History narrative—why wouldn’t they? they’re perched at its zenith—but they also seem to accept the racist dichotomy between savage and civilized at the foundation of many progressive historiographies. In the finale, the dark-skinned eastern “horde” from Essos plays the role of barbaric invaders, juxtaposed, just a few scenes later, against the civilized Westerosi gentry sitting in calm repose about to elect their benign sovereign. By contrast, much of the original story was skeptical of such Western notions of progress, and rejected some of the conventional distinctions between savage and civilized. At times, the story even subverted the traditional dichotomy: for much of the series, it was people from Essos who regarded the Westerosi as “bearded, stinking barbarians.”

“Civilization” in this fictional world is a cruel place, dominated by the “game of thrones,” which itself refers to an endlessly turning wheel of violence and extraction under which peasants are constantly crushed. There’s no indication in the books that history is moving in a direction of improvement for the masses, regardless of who sits on the Iron Throne. Even the one populist incursion (via the religious leader known as the High Sparrow) devolves into co-optation by the monarchy and, ultimately, massacre. While there’s no progress for the peasants at the end, just closed-door machinations by the country’s biggest landlords, it’s implied in the show that we are to smile knowingly, assured that these improvements will eventually trickle down, as long as no more pesky liberators like Daenerys get in the way. The stewards of progress are the same ones who have been turning the wheel that has crushed the peasantry for the last eight seasons—or, rather, their more personally decent sons. Bran and his Team of Rivals will rule the realm justly. But what the show has known and the finale seems to forget is that these amiably debating lords are acting out the same theater on the same stage that almost all politicians act in reality: a friendly face assuring the existence of gradual progress to obscure what will remain forever a system of government and economy that is completely fucking mad.

Perhaps worst of all, the finale is profoundly empty. The show had previously been full of mystery and wonder, meaning and purpose, life and death. Magic, prophecy, high heroic stakes, untamable nature, all seep out of the corners of Westeros and Essos, this vast magical world full of dragons, giants, and zombies that is threatened with utter destruction. The rationalist “Maesters”—composites of secular medieval doctors, political advisors, scribes, and philosophers—are reluctant to acknowledge the growing power of magic and nature thought to be banished to history. Despite their skepticism, the mysteries of nature are obviously reasserting themselves into what appeared to be an otherwise dull, anthropocentric world in which humans think they know and control everything. These mysteries seemed to promise salvation or destruction or both, but they promised something.

Yet by the end, all the magic suddenly re-vanishes back beneath a secular banality of elite striving, oppressive technocracy, and false, vapid myths of progress; in other words, into the maddening blankness of our own unchanging, grimly dull reality. All of this struggle, all the hinted-at meaning and cosmic design, was really all for nothing. The giants are dead. The Children are dead. The last dragon has flown away. The god known as the Lord of Light is silent. The White Walkers were bogeymen, melted away by the dawn. The old aristocrats still rule. Nature and its mysteries, the finale asserts, are dead after all; humans run the world, and that is good, or good enough anyway. The conclusion is morbidly cynical. And one might ask, isn’t the whole show cynical? After all, lots of people in it are brutally murdered for no good reason while many characters are treacherous, cowardly, and cruel, or at least motivated by petty self-interest. But for most of the story, these things were lamented. All the voices of reason and justice agreed, fought against these evils, and the events of the story bore them out: look at how bad these nobles and kings can be. Look at the evil that power creates. Look at how cheaply they treat life. Look at this imbalance of wealth and power. Look at how these crimes are reflected in our own lives by our own leaders. Isn’t that awful? But in the end, such horrific systems remain intact, only instead of deplored, they are presented with smirking, pompous triumph. Grow up nerds, there is no magic, there is no meaning or purpose. Worship your fake democracy and be grateful for your place under the wheel. There is no alternative.