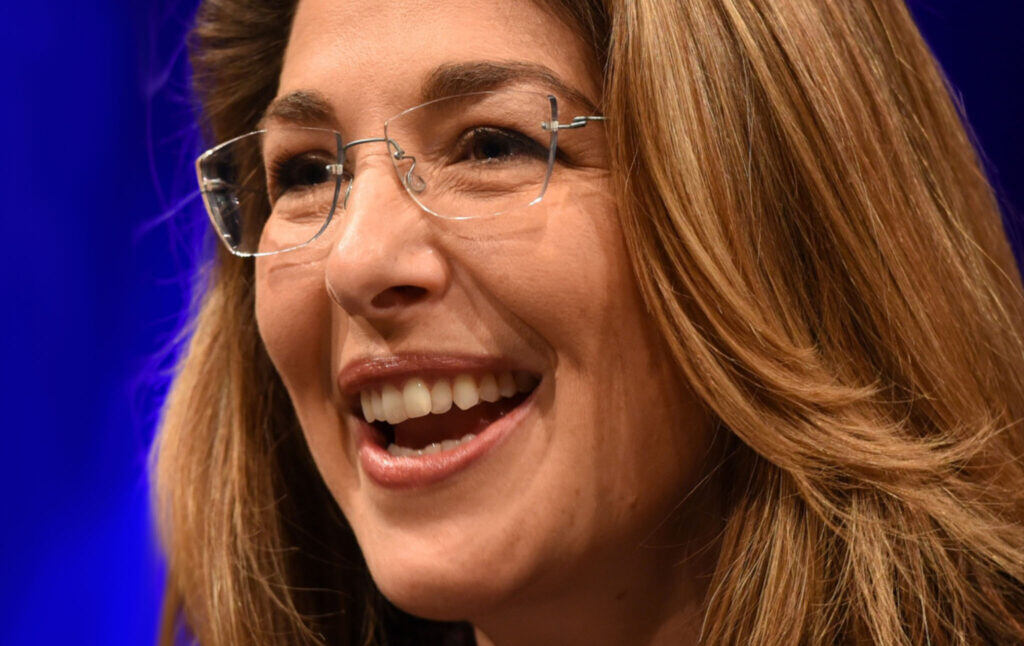

Naomi Klein on Climate Change, the Green New Deal, and Determination

The coronavirus has eclipsed all other news, but climate issues are as real and as imperative as ever. Naomi Klein sat down with our editors to explain what the stakes are and what options we still have available.

Current Affairs editors Nathan J. Robinson and Lyta Gold spoke in October 2019 with writer and climate activist Naomi Klein, author of On Fire: The Burning Case for a Green New Deal. We began by asking her about an article in the New Yorker by Jonathan Franzen called “What If We Stopped Pretending The Climate Apocalypse Can Be Stopped?” which argues that activists (like Klein) are foolish to believe they can meaningfully halt climate change. In the piece, Franzen encouraged a kind of resignation and showed little interest in the kind of ambitious climate policies Klein is pushing for. The interview was transcribed by Addison Kane and has been edited lightly for grammar and readability.

NATHAN J. ROBINSON:

I assume you don’t think that Jonathan Franzen is wrong about how bad the threat of climate change is, but that you disagree with the pessimism, the sense that we’re doomed.

NAOMI KLEIN:

I’ve written a lot about why it is that people on the far right of the political spectrum have to deny the reality of climate change. It’s pretty clear, if you subscribe to a worldview that the market is always right, that people essentially always deserve their fate, that every time people get together to try to do something, terrible things happen—then, climate change is going to make your head explode, because it requires that we get in the way of markets, in a huge way, invest in the public sphere, reverse a whole lot of privatizations, and plan and manage our economy. And, so, it is a profound crisis to that worldview, so the science must be denied.

But there is another worldview that the reality of climate change also finds impossible to metabolize, and that is the worldview of the liberal centrist, who pride themselves on being progressive on various issues, but never taking anything too far or getting too excited about anything. [This person] is generally very suspicious of the riffraff of social movements, and keeps them at a very safe distance, and much prefers the company of birds—not that there’s anything wrong with that! But, so, I think that this cohort, for a while now, has not been denying the science of climate change, but has adopted this posture of melancholic doom in the face of it, because they do understand the science, they do understand how much change is required, but they fundamentally don’t believe in mass organized people. They’re kind of afraid of it. They think it’s kind of cringeful and a little bit scary. Therefore, the verdict is: we’re doomed.

And I see the Franzen piece in that tradition, but he is by no means alone. And it’s in many ways useful that he laid it out in that way. And I think it’s a big part of the reason why, in the presidential Democratic primaries we’re finally having this full throated debate about the Green New Deal, that is so useful, because pretty much everyone alive, almost everyone alive in the United States, right now, doesn’t have a collective memory of a time when people built good things together. Certainly, my historical memory is all about a period of un-making, of dismantling, of chipping away… That is why it is so exciting to me that when we talk about a Green New Deal, we necessarily have to remember the original New Deal, because that revives a memory of when, in the face of peril and crisis, there was an interplay between mass organized people, and politicians willing to be pushed, ushered in an era of very rapid transformation, with social good at the center of the project.

Recognizing all of the failures—recognizing who was excluded: that African-American workers were excluded from many programs, that domestic workers were excluded, that this was an era of a huge number of Mexican-Americans being deported, that there was systemic discrimination—we know all of that, but it is also true that there was a spirit of working-class solidarity during the New Deal era that was very real…

LYTA GOLD:

One of the arguments that Franzen uses, is he argues that human nature itself won’t allow for any sincere climate mobilization. So it’s really funny for you to bring up the fact that we have mobilized society before. One of the essays in On Fire is called “Capitalism Killed Climate Momentum, Not Human Nature.” How much do you see this ideology?

NK:

This argument keeps coming up, right? And it keeps coming up in elite liberal publications that are doing some of the best climate coverage in the world. It’s just when it comes to the idea that people might actually be behind the wheel of history that folks get queasy. Whenever human nature is invoked as the reason why we will or won’t do something, I always become a little bit wary, because humans are many things, and there’s no doubt that we live in a culture that has rewarded parts of our nature that are really incompatible with being able to hold in our heads the severity of the climate crisis, and to be able to come together in a spirit of cooperation and emergency to profoundly transform the way we live.

Now, I don’t think our chances are good. I think we have a pathway, which is very, very, very thin, and very unlikely—that we might just manage to come together in time to change enough that we could keep temperatures below a level where there would still be significant parts of our planet that would continue to support human life. That’s my utopia, by the way! This is why when liberals say, “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” I’m like, that train left the station a long time ago. We’ve already lost Arctic sea ice, the Great Barrier Reef, and we’re losing the Amazon. No one is talking about perfect, okay? We’re talking about survival.

And this is what the student youth movement has inserted into the political debate. That clarity of “we’re fighting for our lives,” which is a message that people living in places like the Marshall Islands and Bangladesh have been trying to get our attention about for a very long time. They’ve been ignored because at the heart of our failure to respond to this crisis is white supremacy. It is the fact that the people who have been most clearly fighting to survive have not been white people. And that’s why climate change has been talked about as an issue off in the future, as huge amounts of coastal Bangladesh disappear, and whole island nations face disappearance, and a large part of Africa becomes uninhabitable because of drought.

NJR:

Your framework is powerful, because it’s a framework of determination, rather than “optimism,” and I guess someone like Franzen doesn’t have to feel the urgency of that determination, because he’s going to be fine.

NK:

The reaction that a lot of people had to that piece was against that posture of “it’s all too late, I’ve done the math and I think our chances are so slim that I’d rather just look after my little patch, here.” That assumes a level of [comfort] that cannot be assumed by the vast majority of people on this planet. So people are fighting for their lives, whether they’re fighting in context of a movement, or whether they’re fighting to get on a leaky boat.

NJR:

You’ve been trying to expand people’s imaginations, like with the video about the future that you did with Molly Crabapple and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. You quote Ursula Le Guin on how capitalism seems so permanent, but the divine right of kings once seemed permanent, too. I constantly come back to that phrase that it’s “easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” and it seems like you’ve been thinking recently that one of the things we need to do is have these visions of what can be possible.

NK:

We did that [recently], at the event with Greta Thunberg. We invited three really young climate activists to, rather than give a speech about what is wrong right now, to put themselves ten years in the future, and tell the story of how we broke through. And some of them are involved in suing the U.S. Government, and they imagine winning that lawsuit, and what it would do, and how it would be enforced, having a rule that has to be enforced, and all of the speakers were actually indigenous, and talked about a revolution in respect for indigenous values, and it was so beautiful. And it was really striking to me that all our speakers were in their 20s, but I think one was in her late teens, and when we gave them this assignment, would you write something from the future, about how we won, they didn’t miss a beat. And they’re like, sure! And reimagining the border, reimagining the relationship with indigenous knowledge, reimagining communities of color that have been systematically neglected, I think they are doing an amazing job with that.

It really made me so hopeful, because I really do think that this generation, the biggest difference is that they’re just not as colonized by neoliberalism as previous generations. They didn’t get the hard sell, because the ideological project has been in crisis their whole lives. They’ve grown up in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, and their imaginations weren’t policed in the same way that people in their 30s and certainly 40s and 50s have had our imaginations policed, and so they’re more capable of imagining a better future, and that makes me really hopeful, because when we wrote The Leap, four years ago, and we had the meeting of 50 movement leaders to try to write this People’s Platform, which is sort of a proto-Green New Deal, it was really hard. adrienne maree brown, who was the incredible facilitator, putting these questions of like, “the future, what does it look like?” And a lot of folks were just like, “Whoa, nobody has ever asked me about that before.” And it was a lot of work to get people—myself included—out of the posture of fighting a game we’ve spent our whole lives on, and imagine what we actually want instead. And so I found it really exciting that it was easy for them to picture that different future.

NJR:

It does feel like a lot has changed in the last year. [In 2018], it was probably pretty unimaginable that CNN would devote seven hours to climate change…I don’t know if it even came up in the 2016 debates.

NK:

It didn’t. And more than that, if you think about when the staccato hurricanes of Irma, and Harvey, and then Maria hit in 2017, CNN and every other major network were systematically not mentioning climate change. They’re still having trouble with it, but any time, if anybody mentioned climate change, in context of those hurricanes, they were accused of politicizing the disaster, there was this idea that it was sort of unseemly to talk about climate change in the midst of a climate-fueled disaster. There are many things that I found striking about that seven-hour climate marathon on CNN, but the most striking moment for me was when they had one huge screen onstage that was showing live footage of a wildfire near Los Angeles, and on the other screen, they were showing live footage of Hurricane Dorian, and in the middle, was the phrase “Climate Emergency.” That is an absolute transformation in the discourse.

LG:

Something you talk about in the book, is the way that there’s been a movement away from complete denialism on the right wing, to just a casual acceptance of eco-fascism. You saw in the Christchurch massacre, the shooter’s manifesto referenced that. Do you feel that there’s going to be a lot more of this just sort of automatic flip to to eco-fascism?

NK:

I mean, yeah, I think the days of outright climate change denialism are numbered. There’s been a strange fixation on “how do you change the mind of a climate denier?” and get them to accept the science, which I’ve always found very misguided, just politically, because I think the much bigger issue is that we have huge numbers of people who do not deny the science, but feel totally hopeless, don’t see a way out, have accepted the human nature argument. That’s much more fertile territory to engage with than trying to convince somebody who denies climate change, because their entire worldview would collapse if the science is true, and we have to do the things that are required to radically lower emissions.

The other reason why it’s incredibly misguided is because you aren’t going to collapse that worldview. It’s interesting, because there’s all kinds of social science that shows that there is an incredibly tight correlation between people who hold what they call a “hierarchical worldview,” and those who deny climate change. Those with a hierarchical worldview, you basically agree with statements like, “people basically get what they deserve.” It’s people who have a fundamental comfort level with massive levels of inequality, because they really do believe the people who are there at the top of the hierarchy are there because they’re better. So, the problem with trying to get those people to believe in climate change is that they aren’t going to let go of their hierarchical worldview, and if they do, and they are starting to admit that climate change is really happening, they’re not going to be like, “hey, let’s rejoin the Paris Accord, and pay our climate debts, and have a justice-based transition.” No. What they are going to do is apply the reality of ecological breakdown, and a future of scarcity, and mass migration to their hierarchical framework. It’s going to have to fit within it.

So, we are already seeing what that looks like. Even if Donald Trump supposedly doesn’t believe in climate change, and thinks it’s a Chinese hoax, as he’s said in a couple Tweets. Trump should know that climate change is happening. He’s had to redesign his golf courses because of sea level rise. He knows it’s happening. But if you are deeply invested in that hierarchical worldview, and you know that climate change is happening, then what you need is a narrative that allows you to justify fortressing the borders, allowing people to die in the desert, in concentration camps, in the Mediterranean. This is what is happening—not just in the United States, it’s happening in Europe, it’s happening in Australia, it’s happening to a lesser extent in Canada. We are seeing what I’m calling climate barbarism, and I definitely would say that it’s the only thing scarier than the proverbial racist uncle whose brain is addled by Fox News, and who denies climate change. The only thing scarier than that is the Fox News addled racist uncle who stops denying climate change, and then uses that as the pretext for why there needs to be an absolutely brutal regime of essentially genocide on the borders.

NJR:

One thing that I wanted to ask you about is this critique that the Green New Deal, because it is an economic policy, a climate policy, and a social policy, the critique that says this is just the left’s wishlist, and they’re just trying to impose it. And you talk about why that isn’t true, and why it is so crucial to have a systemic way of thinking that understands that these elements are inseparable and have to be done together.

NK:

There are a lot of reasons why it’s intensely pragmatic to be as holistic as possible, when we think about how we’re going to transform our economy. One would have to do with backlash. Neoliberal responses to the climate crisis have been tried in many different national governments, or by subnational governments in the United States, whether it’s a carbon tax, or different kinds of fees and tariffs, and in many cases what happens is that you’ll introduce a policy that does very little to lower emissions—certainly not on the scale that we need—but it actually does make life more expensive for working people, and it generates a huge backlash, and the narrative solidifies that people have to choose. Take the slogan of the yellow vest movement in France: “you care about the end of the world, we care about the end of the month.” This idea that caring about the habitability of this planet is some sort of luxury for coastal elites.

So I think backlash is one reason why we shouldn’t be looking for that very narrow climate policy that is just a tax, or just narrowly focused on energy. The other reason is that we need to build coalitions of people who are really going to fight for this. And people fight for their lives, and they fight for their schools, and they fight for jobs, and it is true that we live in a time of tremendous economic stress and precarity, and that people aren’t naturally going to prioritize [climate]. So, if we are able to design policies that marry the need for greater economic security, and dignity, and control of our lives, and basic goods and services, like schools, and healthcare, people are going to fight for that. Not only are they not going to backlash against it, they are going to fight for it, because it’s not just better than a future of apocalypse, it’s better than the lives that they have right now.

Update: the transcript has been updated to correct several transcription errors including the spelling of adrienne maree brown’s name and the gathering of 50 (rather than 15) movement leaders.