Dredging Up the Past

Shoreline expert Megan Milliken Biven writes about dredging vessels, Louisiana, neoliberalism, and her lifelong quest to save her hometown from the sea.

Growing up on the Mississippi River just north of New Orleans, it was not uncommon for a spring deluge to turn our deadend street into a waist-high pool. Just like rings on a tree, hurricane events marked the passing of generations. My parents each had their various tales from Hurricane Betsy in 1965. My own childhood was shaped, in large part, by more recent storms and evacuations. Ask any Gulf Coast resident about that “pre-hurricane feeling” and you’ll likely hear a description of anticipation, giddiness, and dread.

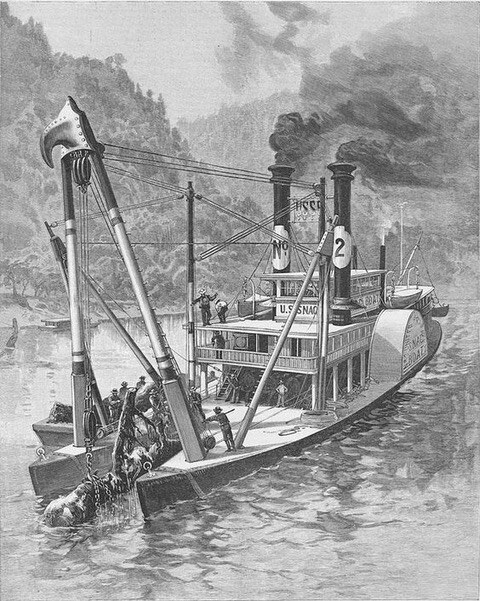

In May 1995, a massive flood inundated our home with three feet of water. All summer long, as workers piled moldy sheetrock and insulation along our street, my twin sister and I explored the strip of woods between our house and the Mississippi River. Drinking cans of Dr. Pepper, we imagined ourselves explorers as we watched the barges and container ships float pass us. I was fascinated by the parade of river traffic—and that fascination stuck with me throughout my childhood. As I grew, so did the size of maritime vessels. Globalization increased the amount of freight traversing the oceans and entering the Port of New Orleans. Larger boats needed deeper ports to safely dock and unload cargo. But this was somewhat of a Sisyphean endeavor, because the Mississippi River is akin to a fire hose of mud and silt. To prevent shoaling (the buildup of sand and sediment), boats called dredge vessels were needed to keep waterways navigable and ports deep enough for vessels to dock.

Dredge vessels are also ships that (literally) shape the land we live on, at least in coastal areas. They were used to build the Palm Islands off the coast of Dubai, and they’re how the low-lying Netherlands fight off the North Sea. There are many kinds of dredge vessels, but for the purposes of this story, the ones we care about are trailing suction hopper dredges, commonly known as “hopper dredges.” These are ocean-going vessels that can endure fierce currents. They do their work by deploying long pipes that suck up sediment on the seafloor, which is then deposited into a large bin, or “hopper,” and then transported to a site for restoration or land-building. I’ve always felt it helpful to think of hopper dredges as the Megamaid from Spaceballs.

By building up the shoreline, hopper dredges help keep Louisiana safe from the sea, but we don’t have nearly enough of them to protect the coastline of my home state, let alone the rest of the country. Currently, the United States’ hopper dredge fleet consists of just 19 vessels, four of which are mothballed by Congress. The other 15 are owned by five private companies. Compare this to the 55 hopper dredges in the Netherlands’ private fleet or China’s ever-growing land-building fleet. With such a paltry collection of vessels, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (which we’ll refer to as “the Corps” going forward) is responsible for maintaining 12,000 miles of inland and intracoastal waterways, 180 ports, and 95,471 miles of shoreline.

History shows the Corps does not have the tools it needs to do its job. Louisiana has lost nearly 1,900 square miles of land since the 1930s and is projected to lose another 674 square miles before 2050. This is land that slows hurricanes down—land that could have slowed Hurricane Katrina down, for example. Louisiana is not the only place in need of dredge vessels, but as with other poor coastal states, many communities are forced to languish on a waiting list that moves too slow to address these emergencies in time. At the time of this writing, most of the nation’s dredge vessels were either drydocked for repairs or deployed across eight far-flung states.

But I knew none of this as a child, a teenager, or even as a young adult. I did not know that Louisiana was sinking into the sea. On August 28, 2005, I had just finished college and was living in Chicago. My siblings and I struggled to convince my mom to evacuate her one-story Lakeview (New Orleans) home, where she’d moved after we went to college. Shortly after she left, Hurricane Katrina’s surge swelled Lake Pontchartrain and turned canals into inescapable tidal waves, overtopping and collapsing poorly designed and long-neglected levees.

Weeks later, my brother, sister, and I snuck back into the city to see our mom’s home and my brother’s apartment. My sister described it like a citywide shipwreck. Perhaps I am imbuing the past with a present sentiment, but it did not feel like a historical anomaly. When I surveyed the city, I felt like I was peering into a hellish future.

The 40-year neoliberal looting of the United States’ physical and social infrastructure guaranteed that any response to Katrina would be slow, militarized, and unequal. Thousands of my neighbors either perished in a horrible instant or languished slowly because of neglect. Had we not convinced my mom to leave, she too would have died, entombed in her own home. For the corporate owners of America’s private dredging fleet, this would have been an acceptable price to pay.

Since the 1970s, the private dredging industry has fought a relentless war to eliminate competition from the public sector. Between 1899 and 1949, the Corps built 150 dredges which were used to develop waterways and ports. But when it came time to replace these aging vessels in the mid-1960s, private businesses saw an opportunity to seize those lucrative contracts for themselves. In 1972, they successfully lobbied Congress into imposing a multi-year dredge moratorium, which intentionally held funds for replacement of public dredges hostage until a “National Dredging Study” on privatizing the fleet could be completed.

Meanwhile, private organizations like Chicago’s Great Lakes Dredge & Dock and the National Association of Dredging Contractors were busy testifying in several Congressional appropriations committee hearings. They argued that before the government even considered building its own new fleet of dredge vessels, it should first consult industry. Surely the free market would be able to provide a more cost-effective solution.

In 1976, a Senate subcommittee held a hearing on proposed legislation to privatize the public dredge fleet. Critics of the move were incredulous, as a private consultancy’s study on privatizing the fleet forecasted that American taxpayers would spend between 20-26 percent more for private industry to do all of the necessary work compared with a publicly-owned fleet. Still, defenders of privatization were dismissive of these findings, evoking now-familiar rhetoric on smaller government and a near-religious faith that private industry competition will keep costs down. When the Corps and industry were grilled on these forecasts, their answers were evasive. Representatives for the Corps explained that they “expect[ed] that the extensive competition which has been available in the past will continue to be available, which should keep the contract bids within a reasonable range.” No evidence was presented to support this claim. It turned out that none was needed. Congress passed the Minimum Fleet Legislation Public Law 95-269 on April 26, 1978. The new policy directed the Corps to utilize its own fleet only when a private bid exceeded the government bid by 25 percent.

Unsurprisingly, it soon became apparent there were too few firms to ensure “real” competition. When the U.S. Department of Justice investigated the dredging industry in the 1980s, they discovered bid-rigging cases against firms across the country. Frank Stockton, then Assistant Deputy Attorney General, explained that because so few firms were in the market—and because they bid on the same projects repeatedly—this naturally “lends itself to bid rigging.” Between 2018-2019, the four firms’ bidding behavior secured an almost even split between the 20 awarded hopper dredging contracts, which is a convenient coincidence for private industry.

Did privatization at least make the actual process of dredging more efficient? Nope. While the costs of dredging steadily increased, the amount of material dredged from ocean and river bottoms did not. The Governmental Accountability Office (GAO) found that fewer vessels and even fewer firms have resulted in higher costs. Between 2003 and 2012, Corps spending on hopper dredging increased by over 117 percent, but the amount dredged only increased by 9 percent.

Thanks to privatization, we’re now stuck with a small, outdated fleet that is demonstrably incapable of meeting the demands presented by a swiftly-changing climate. The Corps is often unable to schedule necessary dredging because of the lack of available vessels. Without its own fleet, the Corps is completely dependent on those 15 privately held dredgers. This imposes serious planning challenges. Justin S. McDonald, Coastal Resiliency Program Manager at the Mobile District, recently explained that the Corps “spend[s] a lot of time thinking when we put projects out and what our acquisition strategies are to not burden other parts of the mission. We start bidding against ourselves. We spend a lot of our time coordinating acquisition.” Please let that sink in. Imagine fighting a war on several fronts and forcing the military to compete for tanks. (Oh…wait it’s 2020, you can imagine this.) Meanwhile, our national infrastructure deteriorates and communities suffer so that a tiny handful of companies can prosper.

Since 2005, I have embarked upon an odyssey to understand what led to the devastating failures of the response to Hurricane Katrina, and how we could prevent this from ever happening again. I wanted to save and rebuild our coast. If it has to do with Louisiana’s environment and coastal crisis, I’ve probably touched it some way or form.

I worked and volunteered for environmental organizations. I counseled homeowners on the importance of home elevation while working for the New Orleans’ City Hall Office of Hazard Mitigation. While I was still in graduate school for public policy, I secured a fellowship that led me to the federal government. I interviewed with what is now called the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) the week of the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster. Knowing nothing about oil and gas, I reasoned that it was time I learned. After all, a good chunk of Louisiana’s ambitious $50 billion master plan to save our coastline hinged on oil and gas revenue. I wanted to understand exactly what we were up against.

Over the years, researching the history of the private American dredging cartel has become my eccentric hobby, the compulsion I return to over and over. Through planning my wedding, building a house, a miscarriage, a move to Houston, a pregnancy, a move back to New Orleans, fighting my federal employer for unpaid maternity leave, having a beautiful baby boy, the shock and fun of my husband quitting his shipyard job, and now a move to Vienna, Austria, I never lost my fascination with this essential yet obscure industry. If there’s a white paper, an obscure 1932 letter to the editor, or congressional testimony on dredging, I’ve read it.

During that same period of time, I was also undergoing my own political and moral transformation. Like many raised in Louisiana, I was steeped in the free-market rhetoric of the Reagan era. When my twin sister and I finished middle school, our parents gave us copies of Ayn Rand’s unreadable Atlas Shrugged and the promise of a crisp $50 bill if we finished it. With this as my intellectual background, I initially approached the dredge fleet problem as a “failure of the market.” I believed that the prospect of facing down a politically powerful dredge lobby was unfeasible. Like many “experts,” I believed we could solve the problem by expanding international competition and overturning the Foreign Dredge Act of 1906, which prevented foreign firms from conducting dredging operations in the United States. This solution, however, would only provide access to the international market. While the international fleet of dredging vessels is larger, cheaper, and more modern, we would still be faced with steep mobilization/demobilization costs and scheduling conflicts—again and again and again. Dredging isn’t a one-off activity, after all. Rivers never stop shoaling, and storms have annual seasons.

In conversations with family and friends, it was routinely suggested that I should make money off this insight by starting my own dredging company or consultancy. The same thought had occurred to others outside my circle. To illustrate: On a flight to D.C. for work, I cornered Louisiana Congressman Garret Graves as he was exiting the restroom. (Hi! I was the lady nursing her kid!) When we spoke about the dearth of dredging capacity, Congressman Graves admitted that he himself had considered starting his own dredging company after his stint as the chairman of the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA). He decided to run for Congress instead.

A core tenet of neoliberalism is that private gain will necessarily result in shared public goods. In reality, it’s the exact opposite. If you’re trying to solve a shared problem or provide a public utility, someone had better get rich in the process. Want coastal protection? Then guarantee a markup to ensure private profit, and you might get it. Want clean water? Well, you’d better sell your public utility to a French transnational. Want to ensure that the dam upriver from you is safe and won’t destroy your town? Well, better make sure that there’s something in it for the company already making money from those currents. This is the modern American Faustian bargain. It is also why the American Society of Civil Engineers’ report card does not rate a single piece of American public infrastructure (roads, levees, drinking water, etc.) above a D-. Our bridges, our water, and our future safety are held ransom. For a public good to be acquired and maintained, it must be exchanged for someone’s private profit.

As I slowly freed myself from the constraints of the neoliberal worldview, I began to understand the tools of my so-called public policy trade were a way to conceal the real ugliness of our decaying infrastructure. When the Corps needs to make a decision about how to deploy the country’s tiny fleet of dredging vessels, it uses a Benefit-Cost Analysis (BCA) to weigh the economic benefits and costs of a project. Property values and economic activity are a major factor in these analyses. This means that areas with lots of high-value properties (e.g., mega-mansions, luxury hotels, oil and gas infrastructure) are more likely to be protected than areas comprising smaller homes and businesses. As wealthier communities are reinforced against the encroaching waters, their property values go up. Meanwhile, as poorer and less developed communities lose land in front of their properties, their property values go down and their insurance rates go up. Since the return on investment isn’t large enough to justify the effort for private companies, working class communities are literally being washed away. The BCA attempts to sanitize what are essentially moral choices by calling them benefits or costs, but the uncomfortable truth is that the program is making choices about what communities are worth protecting.

This isn’t an inevitability—it’s the result of conscious decision-making by powerful entities. As Dale Morris, Director of Strategic Partnerships at the Water Institute of the Gulf and former Congressional Liaison and Economist for the Royal Netherlands Embassy in D.C. explains, “If you have 100 rich people or 1,000 poor people at risk, and the rich people’s property has higher value, investments to protect higher-value property yields a higher BCA and will be prioritized for funding. To most of us, however, investing public dollars to protect 1,000 people makes more sense than protecting only 100 people.” According to Morris, “Current BCA criteria reinforces social and economic inequality and occurs because they do not, yet, capture social benefits or ecosystem provisioning benefits. This is changing, but not quickly enough.”

As a result of these policies, poor people are left alone to deal with the dangers of coastal living while the wealthy get a helping hand to reap its rewards. In his latest book, The Geography of Risk: Epic Storms, Rising Seas, and the Cost of America’s Coasts, journalist and author Gilbert Gaul poses the question: What happens when rich people or businesses don’t have to pay to replace their storm-damaged property? Well, you privatize gains and socialize losses, thus turning the coast into a speculative asset. In a recent conversation Gaul did not mince words: “In terms of restoration, there’s no question that the Corps spends its money on the wealthiest people. They can’t refute it. The largest beneficiaries of their beach-building business are the wealthiest McMansions. Given climate change, is this really how we want to spend limited tax dollars? When you have people begging on the streets, crumbling schools, [do] we want to spend money widening billionaires’ beaches?”

Such an idea seems too absurd to consider with any seriousness. But here we are, with yet another aspect of our shared commons held captive and ransomed by a few private hoarders of capital. In the near future, things could even get worse. There are current legislative efforts that would essentially write a blank check to the dredging industry for multi-year contracts as a strategy to drive costs down. I find this enraging. We can—and should—do a better job of protecting all American residents. Other developed countries have managed to do this, as I learned after moving to Vienna several years ago. While I acknowledge that no place is perfect, everyday I bear witness to policy for the public. It’s mission oriented. It’s universal. It is well staffed. Living in the world’s most livable city has given a direction to my rage, the permission to expect more, and a mandate to demand better. I know we don’t have to sit idly by while working class communities are swallowed by the sea.

It’s undeniable that our nation is facing a coastal crisis. That’s the bad news. The good news is that we’ve overcome similar challenges in the past. Over a century ago, with the Civil War fading into memory and a new generation of immigrants staking their claim to the American dream, the country desperately needed to modernize its major ports so they could accommodate massive new ocean liners like the Lusitania. By mobilizing public resources and support, we were able to do so, and places like New York Harbor became global hubs of commerce and travel.

This did not happen magically. It required the coordinated efforts of many American labor and business groups acting in solidarity to make the case that the country’s interests relied on a robust, technologically advanced public dredge fleet. In the face of frequent private industry critiques and attacks, it required a principled and intentional defense of the public’s right to its own fleet and infrastructure support.

When I sloughed off the constraints of neoliberalism, I began to see a path toward protecting my hometown—and American coastlines in general—from the rising seas (temporarily, at least). We can dream big again. We can repeal the legislation that keeps the tools for defending public lands in the hands of private industry. We can protect working people’s homes and livelihoods by building a new fleet of dredge vessels in regional union shipyards that provide good jobs. We can reject the logic that says the value of a person’s life depends on the size of their house. We’ve done this before, and we can do it again.