You Should Be Terrified That People Who Like “Hamilton” Run Our Country

The American elite can’t get enough of a musical that flatters their political sensibilities and avoids discomforting truths.

In 2012, Captain Dan and his Scurvy Crew, a four-man hip-hop ensemble trying to cement “pirate rap” as a tenable subgenre, appeared on America’s Got Talent. The quartet had clearly put some thought, or at least effort, into the act; their pirate costumes might even have passed historical muster were it not for the leftmost crewmember’s Ray-Bans and Dan’s meticulously groomed chinstrap beard.

The routine itself went precisely in the direction one might have expected:

Captain Dan: When I say yo, you say ho. Yo!

Scurvy Crew: HO!

Captain Dan: YO!

Scurvy Crew: HO!

The group managed to rattle off two-and-a-half stilted lines before the judges began sounding their buzzers. Howard Stern was the last to give them the red “X,” preferring to let the audience’s boos come to a crescendo before he cut the Scurvy Crew off. Stern seemed to take great pleasure in calling the group “stupid,” “moronic,” “idiotic,” and “pathetic” on a national stage (Captain Dan grimaced through his humiliating dressing-down while his bandmates laughed it off, exposing a gap in emotional investment in the project between captain and crew, one that likely led to some intra-group tension during the post-show commiseration drinks).

Howie Mandel: They have restaurants like this—like Medieval Times—where you go and you get a pirates thing and you get a chicken dinner. We didn’t get a chicken dinner with this.

In 2012, everyone (save for Captain Dan himself, along with people whose tastes range from “music from video games” to “music about video games”) was in agreement that performing high-school-history-project rap in Colonial Williamsburg garb was culturally unconscionable. Right?

Wrong. The world in which we live now includes Hamilton, a wildly successful “hip-hop musical” about the first Secretary of the Treasury of the United States of America.

Now, perhaps the America’s Got Talent audience isn’t an accurate sample of the American population as a whole. Perhaps they actually thought “when I say yo, you say ho” was clever , but were directed to boo by an off-screen neon sign. Or perhaps something happened in the past four years that made everyone really stupid.

But what if the American public’s taste hasn’t devolved? What if Hamilton’s success is the result of something else altogether?

Brian Eno once said that the Velvet Underground’s debut album only sold a few thousand copies, but everyone who bought it started a band. The same principle likely applies to Hamilton: only a few thousand people could afford to see it, but everyone who did happened to work for a prominent New York/D.C. publication.

The media gushing over Hamilton has been downright torrential. “I am loath to tell people to mortgage their houses and lease their children to acquire tickets to a hit Broadway show,” wrote Ben Brantley of the New York Times. “But Hamilton… might just about be worth it.” The hyperbolic headlines poured forth unceasingly: “Is Hamilton the Musical the Most Addicting Album Ever?” “Hamilton is the most important musical of our time.” “Hamilton Haters Are Why We Can’t Have Nice Things.” The media then got high on their own supply, diagnosing all of America with a harrowing ailment called “Hamilton mania.” The work was “astonishing,” “sublime,” the “cultural event of our time.” Clarence Page of the Chicago Tribune said the musical was “even better than the hype.” Given the tenor of the hype, one can only imagine the pure, overpowering ecstasy that must comprise the Hamilton-viewing experience. The musical even somehow won a Pulitzer Prize this year, alongside Nicholas Kristof and that book by Ta-Nehisi Coates you bought but never read.

One of the publications to enter swooning raptures over Hamilton was BuzzFeed, which called it the smash musical “that everyone you know has been quoting for months.” (Literally nobody has ever quoted Hamilton in my presence.) BuzzFeed’s workplace obsession with the musical led to the birthing of the phrase “BuzzFeed Hamilton Slack.” That three-word monstrosity, incomprehensible to anyone outside the narrowest circle of listicle-churning media elites, describes a room on the corporate messaging platform “Slack” used exclusively by BuzzFeed employees to discuss Hamilton. J.R.R. Tolkien said that “cellar door” was the most beautiful phonetic phrase the English language could produce. “BuzzFeed Hamilton Slack,” by contrast, may be the most repellent arrangement of words in any tongue.

Those of us unfortunate enough not to work media jobs can never be privy to what goes on in a “BuzzFeed Hamilton Slack.” But the Twitter emissions of the Slack’s denizens suggest a swamp into which no man should tread. A tellingly ominous and thoroughly representative Tweet:

“When the Buzzfeed #Hamilton slack room has a heated debate about which Hogwarts houses the characters belong to” —@Arielle07

“Nerdcore” music (Wikipedia: “a genre of hip hop music characterized by themes and subject matter considered to be of general interest to nerds”) has always had trouble getting off the ground. The “first lady of nerdcore,” rapper MC Router (responsible for the song “Trekkie Pride”), never achieved the critical success for which she had seemed destined, instead ending up on the Dr. Phil show after an acrimonious dispute with her family over her unexpected conversion to Islam. Similarly, the YouTube series “Epic Rap Battles of History,” however numerous its subscribers may have been, has consistently been unjustly robbed of the Pulitzer. Now, finally, nerd rap has apparently found in Hamilton its own Sgt. Pepper, a lofty, expansive work that wins the hearts and minds of previously skeptical elite critics.

One should have no doubt that “expensively-staged nerdcore” is a perfectly accurate, even generous description of Hamilton. Doubters need only examine a brief lyrical snippet. Consider this, from “The Election of 1800”:

Madison: It’s a tie! …

Jefferson: It’s up to the delegates!…

Jefferson/Madison: It’s up to Hamilton!

Hamilton: Yo.

The people are asking to hear my voice ..

For the country is facing a difficult choice.

And if you were to ask me who I’d promote …

Jefferson has my vote.

Perhaps marginally less embarrassing than “when I say yo, you say ho.” But only ever so marginally.

One could question the fairness of appraising a musical before putting one’s self through its full three-hour theatrical experience. But if nobody could criticize Hamilton without having seen it, then nobody could criticize Hamilton. One of the strangest aspects of the whole “Hamiltonmania” public relations spectacle is that hardly anyone in the country has actually attended the musical to begin with. The show is exclusive to Broadway and has spent most of its run completely sold out, seemingly playing to an audience comprised entirely of people who write breathless BuzzFeed headlines. (Fortunately, when you can get off the waitlist it only costs $1,200 a ticket—so long as you can stand bad seats.) Hamilton is the “nationwide sensation” that only .001% of the nation has even witnessed.

There’s something revealing in the disjunction between Hamilton’s popularity in the world of online media and Hamilton’s popularity in the world of actual human persons. After all, here we have a cultural product whose appeal essentially consists of a broad coalition of the worst people in America: New York Times writers, 15-year-olds who aspire to answer the phone in Chuck Schumer’s office, people who want to get into steampunk but have a copper sensitivity, and “wonks.” Yet because a large fraction of these people are elite taste-makers, Hamilton becomes a topic of disproportionate interest, discussed at unendurable length in The New Yorker and Slate and The New York Times Magazine, yet totally inaccessible to anyone besides the writers and members of their close social networks. When The New Yorker writes about a book that nobody in America wants to read, at least they could theoretically go out and purchase it. But Hamilton theatergoing is solely the provenance of Hamilton thinkpiece-writers. The endless swirl of online Hamilton-buzz shows the comical extreme of cultural insularity in the New York and D.C. media. The “cultural event of our time” is totally unknown to nearly all who actually live in our time.

Given that Hamilton is essentially Captain Dan with an American Studies minor, one might wonder how it became so inordinately adored by the blathering class. How did a ten-million-dollar 8th Grade U.S. History skit become “the great work of art of the 21st century” (as the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik says those in his circle have been calling it)?

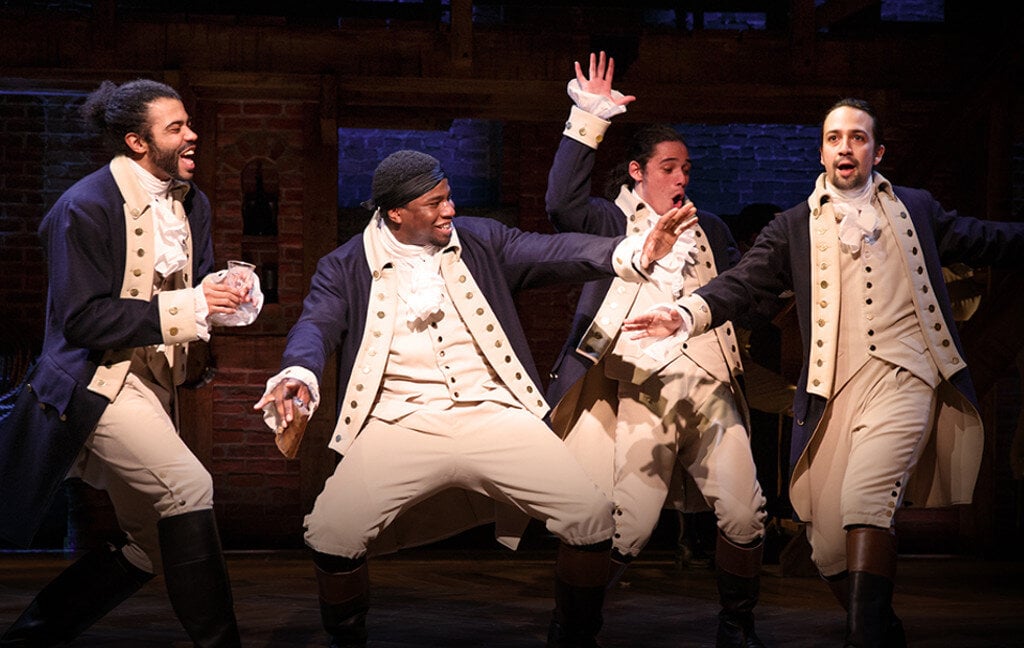

To judge from the reviews, most of the appeal seems to rest with the forced diversity of its cast and the novelty concept of a “hip-hop musical.” Those who write about Hamilton often dwell primarily on its “groundbreaking” use of rap and its “bold” choice to cast an assemblage of black, Asian, and Latino actors as the Founding Fathers. Indeed, Hamilton exists more as a corporate HR department’s wet dream than as a biographical work.

The most obvious historical aberration is the portrayal of Washington and Jefferson as black men, a somewhat audacious choice given that both men are strongly associated with owning, and in the case of the latter, raping and impregnating slaves. Changing the races allows these men to appear far more sympathetic than they would otherwise be. Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda says he did this intentionally, to make the cast “look like America today,” and that having black actors play the roles “allow[s] you to leave whatever cultural baggage you have about the founding fathers at the door.” (“Cultural baggage” is an odd way of describing “feeling discomfort at warm portrayals of slaveowners.”) Thus Hamilton’s superficial diversity lets its almost entirely white audience feel good about watching it: no guilt for seeing dead white men in a positive light required. Now, The New York Times can delight in the novel incongruousness of “a Thomas Jefferson who swaggers like the Time’s Morris Day, sings like Cab Calloway and drawls like a Dirty South trap-rapper.” Indeed, it does take some getting used to, because the actual Thomas Jefferson raped slaves.

“Casting black and Latino actors as the founders effectively writes nonwhite people into the story, in ways that audiences have powerfully responded to,” said the New York Times. But fixing history makes it seem less objectionable than it actually was. We might call it a kind of, well, “blackwashing,” making something that was heinous seem somehow palatable by retroactively injecting diversity into it.

Besides, you don’t actually need to “write nonwhite people into the story.” As historians have pointed out, there were plenty of nonwhite people around at the time, people who already had fully-developed stories and identities. But none of these people appears in the play. As some have quietly noted, the vast majority of African American cast members simply portray nameless dancing founders in breeches and cravats, and “not a single enslaved or free person of color exists as a character in this play.” (Although Jefferson’s slave and mistress Sally Hemings gets a brief shout-out.)

Slavery is left out of the play almost completely. Historian Lyra Monteiro observes that “Unless one listens carefully to the lyrics—which do mention slavery a handful of times—one could easily assume that slavery did not exist in this world.” The foundation of the 18th century economic system, the vicious practice that defined the lives of countless black men and women, is confined to the odd lyrical flourish here and there.

Miranda did consider adding a slavery number. But he cut it from the show, as he explains:

There was a rap battle about slavery, where it was Hamilton and Jefferson and Madison knocking it from all sides of the issue. Jefferson being like, “Hey, I wrote about this, and no one wanted to touch it!” And Hamilton being very self-righteous, like, “You’re having an affair with one of your slaves!” And Madison hits him with a “You want to talk about affairs?” And in the end, no one does anything. Which is what happened in reality! So we realized we were bringing our show to a halt on something that none of them really did enough on.

Miranda found that by trying to write a song about his main characters’ attitudes toward slavery, he ran into the inconvenient fact that all of them willfully tolerated or participated in it. That made it difficult to square with the upbeat portrayals he was going for, and so slavery had to go. Besides, dwelling on it could “bring the show to a halt.” And as cast member Christopher Jackson, who plays George Washington, notes: ‘‘The Broadway audience doesn’t like to be preached to.” Who would want to spoil the fun?

Instead, Hamilton’s Hamilton is what Slate called simply “lovable—a product of the play’s humanizing focus on Hamilton’s vulnerabilities and ambitions.” The play avoids depicting his unabashed elitism and more repellent personal characteristics. And in the brief references that are made to slavery, the play even generously portrays Hamilton as far more committed to the cause of freedom than he actually was. In this way, Hamilton carefully makes sure its audience is neither challenged nor discomforted, and can leave the theater without having to confront any unpleasant truths.

Just as Hamilton ducks the question of slavery, much of the actual substance of Alexander Hamilton’s politics is ignored, in favor of a story that stresses his origins as a Horatio Alger immigrant and his rivalry with Aaron Burr. But while Hamilton may have favored opening America’s doors to immigration, he also proposed a degree of economic protectionism that would terrify today’s free market establishment.

Hamilton believed that free trade was never equal, and worried about the ability of European manufacturers (who got a head start on the Industrial Revolution) to sell goods at lower prices than their American counterparts. In Hamilton’s 1791 Report on Manufactures, he spoke of the harms to American industry that came with our reliance on products from overseas. The Report sheds light on many of the concerns Americans in the 21st century have about outsourcing, sweatshops, and the increasing trade deficit, albeit in a different context. Hamilton said that for the U.S., “constant and increasing necessity, on their part, for the commodities of Europe, and only a partial and occasional demand for their own, in return, could not but expose them to a state of impoverishment, compared with the opulence to which their political and natural advantages authorise them to aspire.” For Hamilton, the solution was high tariffs on imports of manufactured goods, and intensive government intervention in the economy. The prohibitive importation costs imposed by tariffs would allow newer American manufacturers to undersell Europe’s established industrial framework, leading to an increase in non-agricultural employment. As he wrote: “all the duties imposed on imported articles… wear a beneficent aspect towards the manufacturers of the country.”

Does any of this sound familiar? It certainly went unmentioned at the White House, where a custom performance of Hamilton was held for the Obamas. The livestreamed presidential Hamilton spectacular at one point featured Obama and Miranda performing historically-themed freestyle rap in the Rose Garden.

The Obamas have been supporters of Hamilton since its embryonic days as the “Hamilton Mixtape song cycle.” By the time the fully-fledged musical arrived in Washington, Michelle Obama called it the “best piece of art in any form that I have ever seen in my life,” raising disquieting questions about the level of cultural exposure offered in the Princeton undergraduate curriculum.

In introducing the White House performance, Barack Obama gave an effusive speech worthy of the BuzzFeed Hamilton Slack:

[Miranda] identified a quintessentially American story in the character of Hamilton — a striving immigrant who escaped poverty, made his way to the New World, climbed to the top by sheer force of will and pluck and determination… And in the Hamilton that Lin-Manuel and his incredible cast and crew bring to life — a man who is “just like his country, young, scrappy, and hungry” — we recognize the improbable story of America, and the spirit that has sustained our nation for over 240 years… In this telling, rap is the language of revolution. Hip-hop is the backbeat. … And with a cast as diverse as America itself, including the outstandingly talented women — (applause) — the show reminds us that this nation was built by more than just a few great men — and that it is an inheritance that belongs to all of us.

Strangely enough, President Obama failed to mention anything Alexander Hamilton actually did during his long career in American politics, perhaps because the Obama Administration’s unwavering support of free trade and the tariff-easing Trans-Pacific Partnership goes against everything Hamilton believed. Instead, Obama’s Hamilton speech stresses just two takeaways from the musical: that America is a place where the poor (through “sheer force of will” and little else) can rise to prominence, and that Hamilton has diversity in it. (Plus it contains hip-hop, an edgy, up-and-coming genre with only 37 years of mainstream exposure.)

The Obamas were not the only members of the political establishment to come down with a ghastly case of Hamiltonmania. Nearly every figure in D.C. has apparently been to see the show, in many cases being invited for a warm backstage schmooze with Miranda. Biden saw it. Mitt Romney saw it. The Bush daughters saw it. Rahm Emanuel saw it the day after the Chicago teachers’ strike over budget cuts and school closures. Hillary Clinton went to see the musical in the evening after having been interviewed by the FBI in the morning. The Clinton campaign has also been fundraising by hawking Hamilton tickets; for $100,000 you can watch a performance alongside Clinton herself.

Unsurprisingly, the New York Times reports that “conservatives were particularly smitten” with Hamilton. “Fabulous show,” tweeted Rupert Murdoch, calling it “historically accurate.” Obama concluded that “I’m pretty sure this is the only thing that Dick Cheney and I have agreed on—during my entire political career.” (That is, of course, false. Other points of agreement include drone strikes, Guantanamo, the NSA, and mass deportation.)

The conservative-liberal D.C. consensus on Hamilton makes perfect sense. The musical flatters both right and left sensibilities. Conservatives get to see their beloved Founding Fathers exonerated for their horrendous crimes, and liberals get to have nationalism packaged in a feel-good multicultural form. The more troubling questions about the country’s origins are instantly vanished, as an era built on racist forced labor is transformed into a colorful, culturally progressive, and politically unobjectionable extravaganza.

As the director of the Hamilton theater said, “It has liberated a lot of people who might feel ambivalent about the American experiment to feel patriotic.” “Ambivalence,” here, means being bothered by the country’s collective idol-worship of men who participated in the slave trade, one of the greatest crimes in human history. To be “liberated” from this means never having to think about it.

In that respect, Hamilton probably is the “musical of the Obama era,” as The New Yorker called it. Contemporary progressivism has come to mean papering over material inequality with representational diversity. The president will continue to expand the national security state at the same rate as his predecessor, but at least he will be black. Predatory lending will drain the wealth from African American communities, but the board of Goldman Sachs will have several black members. Inequality will be rampant and worsening, but the 1% will at least “look like America.” The actual racial injustices of our time will continue unabated, but the power structure will be diversified so that nobody feels quite so bad about it. Hamilton is simply this tendency’s cultural-historical equivalent; instead of worrying ourselves about the brutal origins of the American state, and the lasting economic effects of those early inequities, we can simply turn the Founding Fathers black and enjoy the show.

Kings George I and II of England could barely speak intelligible English and spent more time dealing with their own failed sons than ruling the Empire —but they gave patronage to Handel. Ludwig II of Bavaria was believed to be insane and went into debt compulsively building castles — but he gave patronage to Wagner. Barack Obama deported more immigrants than any other president and expanded the drone program in order to kill almost 3,500 people — but he gave patronage to a neoliberal nerdcore musical. God bless this great land.

This article originally appeared in our July/August print edition.