Bill Clinton’s Shameful Genocide Denial

Clinton’s actions during the Rwandan genocide were worse than is usually remembered…

“If the horrors of the Holocaust taught us anything,” Bill Clinton said before becoming president, “it is the high cost of remaining silent and paralyzed in the face of genocide. Even as our fragmentary awareness of crimes grew into indisputable facts, far too little was done. We must not permit that to happen again.”

Clinton’s words were stirring, but they reflected a broad consensus among the Western powers after World War II: another Holocaust could not be allowed to occur. By the time of the Clinton Administration, this had become an article of American political faith, one of the country’s few solid moral commitments: whatever other misfortunes we might inflict through our actions and inactions across the globe, the United States would never permit the tragedies of 1939-1945 to replay themselves.

The events in Rwanda during 1994 would be the true test of the country’s commitment to the principle. It was the precise scenario that each president had solemnly sworn an oath to prevent. Moreover, the country had the resources, opportunity, and knowledge necessary to help. It was, fundamentally, an event that could have been stopped, or at least significantly mitigated, through the taking of steps that were known and feasible. But over the course of 100 days, as literally hundreds of thousands of bodies piled up in Rwanda, President Clinton did exactly what he had promised he would never do; he remained “silent and paralyzed in the face of genocide,” and even as his “fragmentary awareness grew into indisputable facts,” he lackadaisically “permitted it to happen again.”

But even worse, and seldom acknowledged, is that Clinton did something far worse. He did not just “sit on his hands”: he deliberately stalled the efforts of others to intervene, and went so far as to deny the genocide in order to avoid being pressured to stop it.

The most important thing to understand, in analyzing international responsibility for the genocide, is whether enough information was available to the decision-makers. A person cannot be held accountable for not stopping something he did not know was occurring. Indeed, Bill Clinton, according to Samantha Power, “is said to have convinced himself that if he had known more, he would have done more.” He claimed in 1998 that he did not “fully appreciate the depth and the speed with which [Rwandans] were being engulfed by this unimaginable terror.” Clinton offers his present-day charitable works in Rwanda as proof that once he is made aware of suffering there, he will dedicate himself diligently to alleviating it, that he would never leave Rwanda to perish if he knew he was capable of acting.

But Clinton’s claim not to have fully understood the situation is a lie. Clinton knew. Knew there was a genocide, knew its scale. People at all levels of government knew. It was all over the press. In fact, the idea that any informed official at the time could plead ignorance to the Rwandan genocide is laughable. As time passes, it may be easier and easier to blur the history, to suggest that everything was opaque and uncertain and that it would have taken impossible omniscience in order to understand. But the violence in Rwanda was in the newspapers. It wasn’t just the stuff of minor internal State Department memoranda and overlooked faxes at the bottom of receptionists’ inboxes. It was in The New York Times and The Washington Post. The Administration’s spokespeople was being regularly asked about it.

It’s easy enough, if we know nothing about it, to accept the proposition that the scale of the Rwanda genocide became clear only after the fact. Fog of war and all that. It certainly comports with the received image of Africa as a dark and unfathomable continent, out of which reliable information never flows. But any glance through contemporary sources instantly invalidates this view of history. To say one didn’t know is not just implausible or unlikely. It is a lie.

When assessing the question of “knowledge,” and the subsequent issue of culpability, it is vital to keep in mind the timeline of the genocide, and to figure out what information was available at what points. Again, remember that President Clinton, in tearfully apologizing to Rwandans, said he did not “fully appreciate the depth and the speed” with which Rwandans were being engulfed by this unimaginable terror.”

On April 6th, 1994, the day before the Rwandan genocide began, the country’s president had been assassinated, his plane shot down over Kigali by parties unknown. It was the small spark necessary to trigger a genocide; the president was a Hutu, and the killing provided the necessary pretext for the country’s military forces to carry out a plan they had been working on for some time: the extermination of their ethnic rivals, the Tutsi minority. On April 7th, a motley assemblage of paramilitary forces, under the direction of high-ranking members of the political elite, began a concerted program of mass slaughter. Inspired by an apocalyptic “Hutu Power” ideology, and fueled by “hate radio” stations commanding ordinary citizens to kill, groups of machete-wielding death squads roamed through the country, killing every Tutsi they could find, as well as moderate Hutus. In this nationwide paroxysm of stabbing, raping, and shooting, hundreds of thousands would be killed over the next 100 days.

The Rwandan president was assassinated on the 6th, a Wednesday. The killings began on Thursday the 7th and lasted three months. On the Thursday, members of the Presidential Guard killed eleven Belgian UN peacekeepers, as well as the Rwandan prime minister. On Friday the 8th, Bill Clinton publicly stated that the prime minister had been “sought out and murdered. Reuters described a “wave of bloodletting” in which “embers of the security forces and gangs of youths wielding machetes, knives and clubs rampaged through the capital, Kigali, settling tribal scores by hacking and clubbing people to death or shooting them.”

On Saturday, April 9th, Clinton included references to Rwanda in his weekly radio address (which was “otherwise devoted to crime and other domestic issues” and focused largely on Clinton’s pitch for his crime bill.) Of the situation there, he said:

Finally, let me say just a brief word about a very tragic situation in the African nation of Rwanda. I’m deeply concerned about the continuing violence… There are about 250 Americans there. I’m very concerned about their safety, and I want you to know that we’re doing all we can to ensure their safety.

That same day, United Nations observers in Kigali witnessed a massacre that took place in a Polish church, in which over one hundred people including children were brutally hacked to death. The New York Times described Rwanda and Burundi as “two nations joined by a common history of genocide,” raising the specter of the g-word.

On the 11th, The New York Times published the accounts of Americans who had recently evacuated:

‘It was the most basic terror,’ said Chris Grundmann, 37, an American evacuee, describing the fears of the Rwandan civilians and officials who were targets of the violence. He and his family, hunkered down in their house with mattresses against the windows, heard the ordeals of Rwandan victims over a two-way radio.‘The U.N. radio was filled with national staff screaming for help,’ he said. ‘They were begging: ‘Come save me! My house is being blown up,’ or ‘They’re killing me.’ There was nothing we could do. At one point we just had to turn it off.’ Since Wednesday, it is estimated that more than 20,000 people have been killed in fighting between the Hutu majority and the Tutsi minority that have struggled for dominance since Rwanda won independence from Belgium in 1962. On Friday alone, the main hospital had many hundreds of bodies before noon. Mr. Grundmann, an official with the Centers for Disease Control [said that] the family’s cook, a Tutsi, came to their home begging for help on Friday after having spent three days pretending to be dead. ‘He told us that on Wednesday night someone had thrown a grenade into his home… He escaped through an open window, but he thinks his wife and children died. For 36 hours he played dead in a marsh. There were bodies all through the marsh. He said there were heads being thrown in.’

On April 12th, The New York Times printed a profile of several Adventist missionaries who had fled:

“Now that we are out,” Mr. Van Lanen said today, “I fear, in a way, that we have betrayed the people we came to help. Now, they fear that most of those people—deprived of their protection—will become victims of the bloodletting that has set the majority Hutu tribe of Rwanda against the minority Tutsis. Red Cross officials estimate that the violence has taken more than 10,000 lives in Kigali alone, and as many or more in the countryside

That same day, Toronto’s Globe and Mail ran a report containing interviews with traumatized Canadians who had evacuated:

“There were bodies everywhere. Wounded people were not getting any attention. Women with children on their backs were hacked to pieces. I saw one man still alive who was disembowelled, another had almost been cut in half with a panga (a long, sharp knife).” The streets of Kigali were like a “slaughterhouse” and “blood was literally flowing in the gutters.”

On the 15th, The New York Times published a report about the refugees gathered in at the Hotel Milles Collines, later made well-known in the film Hotel Rwanda:

In Kigali, scores of Rwandans have taken refuge at the Hotel Mille Collines. There is an uneasy, nervous coexistence there between the families of the Rwandan military and some middle-class Tutsis who were unable to leave the city. Both are convinced they will be massacred. They congregate in the dark hallways, whispering for hours, virtual prisoners. As United Nations soldiers came to take the foreign journalists to the airport, dozens of the Rwandans crowded around and begged to be evacuated, fearing that the departure of Westerners would mean sure death for them. Their pleas were rejected by the troops. As the convoy left, many gathered silently in the driveway and stared.

On the 16th, the Montreal Gazette published a desperate plea from a Rwandan exile, under the headline “Don’t abandon us”:

[Fidele Makombe] says he was stunned by the orgy of murder, rape and torture unleashed in the small central African nation… Human-rights observers are convinced that the coterie of ethnic Hutus around the president used the incident as a pretext to unleash a reign of terror… Makombe, who runs the Rwandese Human Rights League from his base here, is appealing to the world not to kiss off Rwanda as another African human-rights basket case, but to understand the true nature of the conflict…

The killings in Rwanda were no secret, then. Every day, the papers were full of them; these are random examples, one could offer many, many more clippings from the Washington Post, The New York Times, and the various wire services, and these were just from the first weeks of a genocide that went on unimpeded for three months without Clinton acting. By April 24th, the Sunday Washington Post was filled with pleas from Human Rights Watch, who explained unequivocally what was going on:

We put the word genocide on the table. We don’t do it lightly. There is clearly here an intention an eliminate the Tutsi as a people… This is not “inter-tribal fighting” or “ethnic conflict.” First, it’s not fighting, it’s slaughter…

A front page Post story from the same day described “the heads and limbs of victims… sorted and piled neatly, a bone-chilling order in the midst of chaos that harked back to the Holocaust.”

To not “fully appreciate” what was going on would have required not glancing at a newspaper for the three months from the beginning of April to the beginning of July.

It’s important to provide excerpts from some of these contemporary media accounts, so as not to accidentally lapse into believing that the genocide was something hidden or unknown. After such a calamity, for which so many are culpable, a great number of people have vested interests in downplaying the extent to which the genocide was (1) knowable and (2) preventable. If only to spare themselves a lifetime of guilt, they must publicly repeat that the situation was unclear, and that nothing could be done. But the historical record says otherwise; very little was unclear, and even those things that were unknown on April 8th were certainly clear by the 20th, when fleeing survivors’ reports of genocide were being recounted in the press daily. As April turned to May, the nation’s papers were openly puzzled by Clinton’s refusal to do anything. On May 2nd, the editorial board of USA Today angrily denounced Clinton for his uselessness:

Imagine the horror of watching 25 mutilated bodies float down a local river – every hour. Try to picture 250,000 North Carolinians abandoning their homes and belongings in a terrified run for their lives from machete-wielding madmen. That’s what life is like these days in Rwanda, a small but densely populated Central African nation where as many as 200,000 men, women and children have been slaughtered in the past three weeks… Where is the world’s horror? And, more immediately, where is the world’s outrage? Surely, if hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians were hacked to death in France or Germany, the international call for action would be swift and strong. But Rwanda is in Africa. And, unfortunately, the Western world reacts slowly to black-on-black violence. President Clinton, who criticized George Bush for not doing more to stop ethnic cleansing in Bosnia, certainly took his time getting around to this genocide. Only last weekend did he finally deliver a radio address, broadcast in Rwanda, pleading for an end to the violence. That’s about three weeks – 200,000 victims – too slow.

But if the editors at USA Today thought Clinton would spring into action after 200,000 victims, they were mistaken. Besides the evacuation of Americans, Clinton’s radio address to Rwandans (which Human Rights Watch called “so mild as to be worthless”) would constitute the full extent of the U.S.’s action in the country until July.

In fact, there was a conscious commitment to inaction by the Clinton Administration. As Princeton Lyman, then serving as U.S. Ambassador to South Africa recalls, “[p]eople knew what was going on…There certainly was information flowing in. The African Bureau at the State Department was pleading for the Pentagon to bomb the hate radio stations. People had information. There was just a reluctance to do very much.” Former State Department military advisor Tony Marley describes a meeting at the State Department:

One official even asked a question as to what possible outcome there might be on the congressional elections later that year were the administration to acknowledge that this was genocide taking place in Rwanda and be seen to do nothing about it. The concern obviously was whether it would result in a loss of votes for the party in the November elections… I was stunned because I didn’t see what bearing that had on whether or not genocide was, in fact, taking place in Rwanda. Partisan political vote-gathering in the U.S. had no bearing on the objective reality in Rwanda.

Marley said that even modest proposal for action were instantly rejected. When Marley suggested that they at least attempt to jam the frequencies hate radio stations that were fueling the genocide, a State Department lawyer told him it would go against the spirit of the U.S. Constitution’s commitment to free speech. (For the record, United States constitutional law does not protect the right to order a genocide on the radio.)

But the Clinton Administration actually did something much, much worse than failing to intervene. It deliberately attempted to downplay the atrocities, refusing to refer to them publicly as genocide, for fear that doing so would obligate them under the U.S.’s Genocide Convention to take action. As The Guardian reported in 2004, classified documents showed that “President Bill Clinton’s administration knew Rwanda was being engulfed by genocide in April 1994 but buried the information to justify its inaction… Senior officials privately used the word genocide within 16 days of the start of the killings, but chose not to do so publicly because the president had already decided not to intervene.” “Detailed reports” were reaching the top levels of government; Secretary of State Warren Christopher “and almost certainly the president” had been told mid-April that there was “genocide and partition” and a “final solution to eliminate all Tutsis.” The CIA’s national intelligence briefing, circulated to Clinton, Al Gore, and other top officials, “included almost daily reports on Rwanda,” with an April 23 briefing saying that rebels were attempting to “stop the genocide, which… is spreading south.” As William Ferroggiaro of the National Security Archive explained, declassified documents show that “[d]iplomats, intelligence agencies, defense and military officials – even aid workers – provided timely information up the chain… That the Clinton administration decided against intervention at any level was not for lack of knowledge of what was happening in Rwanda.” Joyce Leader, U.S. Embassy’s deputy chief of mission in Kigali, admitted in 2014 that “We had a very good sense of what was taking place.”

But nobody in the United States government was willing to use the word “genocide” publicly. The United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide contains a binding requirement that countries prevent genocide, so acknowledgment of the genocide would have created a legally binding mandate to stop it. Even though internally, members of the Clinton Administration were referring to a genocide, publicly their spokespeople were under strict orders to refuse to confirm that a genocide was occurring, for fear that it “could inflame public calls for action.”

“Be careful,” warned a document from the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense’s office, “Legal at State was worried about this yesterday – Genocide finding could commit U.S.G. to actually ‘do something.’”

The resulting press conferences took Clintonian hairsplitting to its most absurd outer limits. Here, reporters try to pin down State Department spokesperson Christine Shelley and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright:

REPORTER 1: —comment on that, or a view as to whether or not what is happening could be genocide?

CHRISTINE SHELLEY: Well, as I think you know, the use of the term “genocide” has a very precise legal meaning, although it’s not strictly a legal determination. There are—there are other factors in there, as well. When—in looking at a situation to make a determination about that, before we begin to use that term, we have to know as much as possible about the facts of the situation.

REPORTER 2: Just out of curiosity, given that so many people say that there is genocide underway, or something that strongly resembles it, why wouldn’t this convention be invoked?

MADELEINE ALBRIGHT: Well, I think, as you know, this becomes a legal definitional thing, unfortunately, in terms of—as horrendous as all these things are, there becomes a definitional question.

Finally, at the end of May, as hundreds of thousands lay dead across Rwanda, the Clinton Administration changed its policy and began using the term. But even then they took great pains to use a carefully-constructed legalism; while they would admit that there may have been “acts of genocide” occurring, they drew a distinction between these and “genocide,” in the apparent belief that this would keep them from triggering the Genocide Convention.

Again, reporters tried to get a straight answer:

CHRISTINE SHELLEY: We have every reason to believe that acts of genocide have occurred.

ALAN ELSNER (REUTERS): How many acts of genocide does it take to make genocide?

CHRISTINE SHELLEY: Alan, that’s just not a question that I’m in a position to answer.

ALAN ELSNER: Is it true that the—that you have specific guidance not use the word “genocide” in isolation, but always to preface it with this—this word, “acts of”?

CHRISTINE SHELLEY: I have guidance, which—to which I—which I try to use as best as I can. I’m not—I have—there are formulations that we are using that we are trying to be consistent in our use of.

Alan Elsner later described his incredulity at the Administration’s non-responsiveness:

The answers they were giving were really non-answers. They would talk in incredibly bureaucratic language. In a sense, it was almost like a caricature. If you look at it now, it looks utterly ridiculous. These were all kind of artful ways of doing nothing, which is what they were determined to do.

Not only did the Clinton Administration adopt a policy of refusing to recognize the genocide, but it pressured other countries to do the same. Former Czech Ambassador to the U.N. Karel Kovanda recalled that his government was pressured by the U.S. not to use the term:

KAREL KOVANDA: I know that I personally had an important conversation with one of my superiors in Prague who at American behest suggested that they lay off.

INTERVIEWER: Lay off calling it genocide?

KAREL KOVANDA: Yeah. Lay off pushing Rwanda, in general, and calling it genocide specifically.

INTERVIEWER: So the Americans had actually talked to your government back in Prague and said, ‘Don’t let’s call it genocide.’

KAREL KOVANDA: In Prague or in Washington, but they were talking to my superiors, yes.

There is much to be revolted by here. Despite Clinton’s promise that he would never sit idly by while genocide was occurring, not only was he doing exactly that, but his administration actually perpetrated a planned act of genocide denial specifically in order to avoid having to prevent a genocide from occurring. As The Guardian reported, the Clinton Administration, “felt the US had no interests in Rwanda, a small central African country with no minerals or strategic value.” Thanks to Rwanda’s lack of minerals, the world’s most powerful nation was content to let 800,000 people have their faces chopped off with machetes.

But even this underplays the Clinton Administration’s responsibility. It’s true that the U.S. government both deliberately refused to send forces to Rwanda and deceived the world about whether a genocide was occurring. It’s also true that both then and now, Bill Clinton pretended that there was too little information to come to any conclusions all while receiving detailed briefings on the genocide (as it was simultaneously splashed across the daily papers). But perhaps even worse, the Clinton Administration actually took affirmative steps to keep the United Nations from sending a force to Rwanda. As Samantha Power explains:

In reality the United States did much more than fail to send troops. It led a successful effort to remove most of the UN peacekeepers who were already in Rwanda. It aggressively worked to block the subsequent authorization of UN reinforcements.

“Recall,” said former special envoy to Somalia Robert Oakley, “it wasn’t just not sending U.S. forces: we blocked a security council resolution to send in a U.N. force.” Indeed, Clinton Administration deliberately stalled United Nations efforts to coordinate an intervention. According to Foreign Policy, “[w]hen the genocide began, the United States launched a diplomatic campaign aimed at bringing the U.N. peacekeepers home. Initially, Washington sought to shutter the mission entirely.” On May 17th, The New York Times reported that “The United States forced the United Nations… to scale down its plans and put off sending 5,500 African troops to Rwanda in an effort to end the violence there… Washington argued that sending in a large peacekeeping force raised the risk of the troops’ being caught up in the fighting.” There was “a decisive U.S. role in the tragic pullout of United Nations peacekeepers” and each time the United Nations attempted to formulate a modest plan for reprieve, the United States stalled it, even to the extent of using its Security Council veto power over other nations.

One may wonder why the Clinton Administration acted so callously in the face of such a preventable catastrophe. But one need not wonder long. The relevant considerations were explained by Bill Clinton during his commencement speech at the Naval Academy in May of 1994, during the middle of the genocide:

Now the entire global terrain is bloody with such conflicts, from Rwanda to Georgia… Whether we get involved in any of the world’s ethnic conflicts, in the end, must depend on the cumulative weight of the American interests at stake.

There, in plain language, was Clinton’s philosophy. “The cumulative weight of the American interests at stake” were the deciding factor when it came to “ethnic conflicts” like the Rwandan genocide. With few American interests in Kigali (no minerals), there was little that needed to be done.

Clinton’s close political advisor, Dick Morris, was even more explicit in describing the president’s reasoning:

The real reason was that Rwanda was black. Bosnia was white. European atrocities mattered more than African atrocities—not to Clinton himself, but to the media, which covered the grisly deaths in Yugoslavia but devoted considerably less attention to the genocide in Africa. And without the media dogging him to take action, Bill Clinton…wasn’t about to pay attention.

The words of a jaded and disreputable operative like Dick Morris may of course be taken with some skepticism. And he underplays the extent to which the media was covering the genocide. But as USA Today noted, it’s hard to believe that if the same circumstances had occurred in a European country, Clinton would have shown the same level of indifference. The president’s treatment of Rwanda had everything to do with a political calculus; Administration officials were openly concerned with the situation’s effects on the November election. (They lost anyway.)

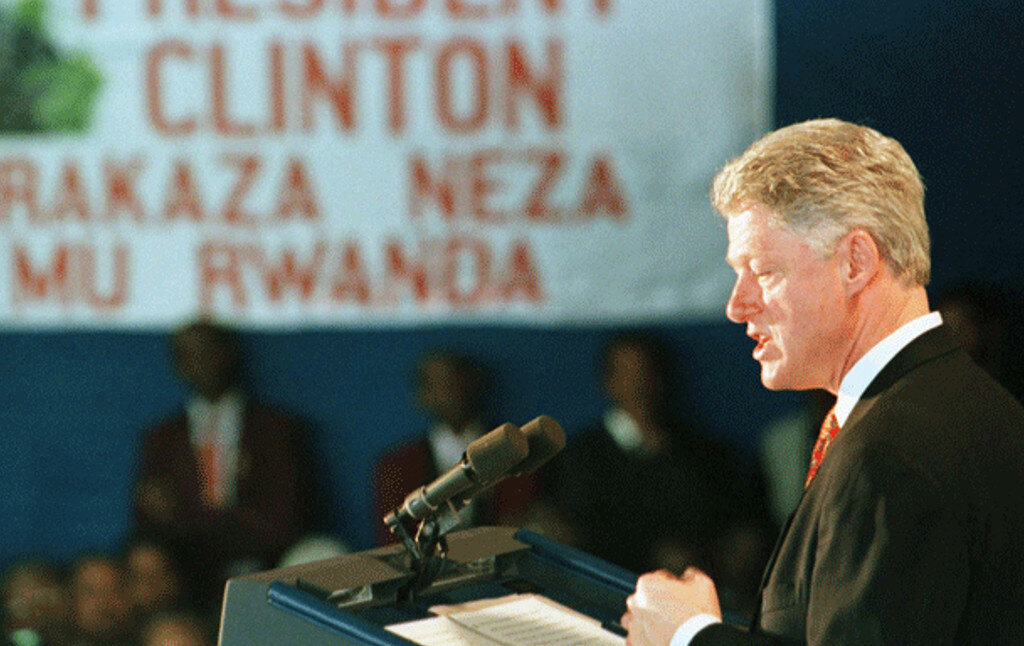

Bill Clinton has struggled to explain why he did not intervene in Rwanda. In 1998, he visited Kigali and offered what some have described as an “apology,” though it did not contain much actual apologizing. In that statement, Clinton admitted that “[i]t may seem strange to you here, especially the many of you who lost members of your family, but all over the world there were people like me sitting in offices, day after day after day, who did not fully appreciate” the depth of the terror.

Indeed it did seem strange, because it was, in fact, impossible. As Rwanda scholar Timothy Longman wrote, “Clinton’s claims were false. It is not that the U.S. government didn’t know what was happening in Rwanda. The truth is that we didn’t care.” And as Samantha Power has concluded, “[a]s the terror in Rwanda had unfolded, Clinton had shown virtually no interest in stopping the genocide, and his Administration had stood by as the death toll rose into the hundreds of thousands.”

Even as he constructed the appearance of regret, then, Bill Clinton was engaging in political spin. Dana Hughes of ABC News reports on an internal memo from late in 1994, offering talking points with which the president could cover himself. The memo:

suggests the president argue that the United States took appropriate and swift action in Rwanda after it was clear there was genocide, and that the U.S. was one of many countries who authorized the United Nations to pull out of the country right before the atrocities began. In short, says the memo, the U.S. ‘did the right thing’ and shares no responsibility for allowing the genocide to occur. Clinton himself echoed these sentiments in comments to the press a few months earlier where he said he had ‘done all he could do’ to help the people of Rwanda.

One of the most disturbing aspects of Clinton’s conduct around Rwanda is that he has been willing to lie about it and twist it in order to paint himself as sincerely oblivious and well-intentioned. The existing evidence incontrovertibly proves that Clinton failed to intervene because he didn’t see anything to be gained domestically. This is not a conspiracy theory, or a speculative hypothesis. Clinton’s own words from the time of the genocide, about the “cumulative weight of American interests,” affirm what witnesses from his Administration have said.

The evidence also proves that the Clinton Administration went far beyond inaction. It also attempted to stop others from acting. But worst of all, it adopted a conscious policy of genocide denial. It knew there was a genocide, but publicly fudged the truth so as not to have to stop it. This is actually far, far worse than even Holocaust denial; after all, the most harmful time to deny a genocide is while it is occurring, especially if your denial made deliberately so that nobody will stop the genocide. At the peak of one of the 20th centuries worst mass slaughters, Bill Clinton presided over an act of institutionalized genocide denial so as to allow the slaughter to continue.

Perhaps, in a just world, Bill Clinton would in prison for conspiracy to deny a genocide. But we live in this world, in which he is likely to return to the White House.

Adapted from the upcoming Current Affairs book “Superpredator: Bill Clinton’s Use and Abuse of Black America.” Pre-order today for shipping July 1st.