The Declining Taste of the Global Super-Rich

Today’s “patrons of the arts” are less interested in opera and ballet, and more interested in novelty furniture and enormous sculptures of their own faces…

Last May, with little to no fanfare, the Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet in New York City closed down after 12 years, leaving about 16 dancers and about 10 administrators out of a job. The company’s dissolution, quietly announced on Observer.com, was a particularly tragic loss for the dance world, which requires an innovative atmosphere to sustain itself.

Funding for even venerable ballets grows scarcer and scarcer, and more experimental operations like Cedar Lake are even more vulnerable. It’s a sort of “last hired, first fired” set of priorities, and as a result, the institution of ballet itself is threatened with stagnation. Swan Lake and The Nutcracker are exemplary classics to be sure, but without daring and contemporary new ballets, the artform itself becomes relegated to antiquity. In America specifically, ballet increasingly smacks of a bygone era, making it less attractive to potential funders.

So the bankrolling of ballets has been left to a few super-wealthy benefactors. For Cedar Lake, it was Walmart heiress Nancy Walton Laurie, who invested $11 million of her estimated $4.5 billion fortune to found the project. Laurie gave Cedar Lake a custom-built theater and rehearsal space in Chelsea, and stocked it with a full roster of talent. Boasting job security nearly unheard-of in the dance world, Laurie paid the staff and dancers full-time salaries with vacation, health insurance and even dental.

Unfortunately, the company was notoriously mismanaged. Turnover was high; the bestowing of dental coverage didn’t compensate for otherwise-dire working conditions. The dancers were actually fined for lateness and performance mistakes, a shockingly repressive practice unheard of even in the legendarily regimented dance world.

Both former dancers and employees would later paint Cedar Lake as the vanity project of an imprudent billionaire, who was, unfortunately, their only real donor. Her whims lent the project both its generosity and its tyranny, and when the whims shifted, the ballet was no more.

In recent conversation, a professional opera singer lamented to me the the state of his profession under recent funding woes. The trajectory for an opera singer, he told me, used to be a fairly established route. A singer would graduate from a conservatory, then spend a couple of years performing for some backwater German town to hone their skills—a sort of apprenticeship that both developed the artist’s voice and brought opera—a much more appreciated artform in Europe—to a smaller community.

Such is no longer the case. The austerity measures taken across Europe have dealt arts funding a serious blow, particularly in the less wealthy countries. In 2012, The New York Times reported that not only were the smaller opera houses getting the ax, but even once sacrosanct institutions were under fire; the legendary La Scala opera house in Milan was landed with a $9 million dollar deficit that year. Smaller countries like the Netherlands lost 25% of their arts funding, and Portugal dispensed with its Ministry of Culture entirely.

Some companies attempted to adapt to shoe-string budgets by going “punk”—doing away with famously grand productions in favor of sparser shows, and even a few “experimental” one-man performances.

“It’s austerity for opera,” proclaimed the exasperated tenor. When I admitted to him that the only opera I can afford these days are sparse, DIY productions at a loft in Bushwick, he was encouraging, saying “that’s great—just go.” But there’s no getting around now the fact that there’s something missing from a minimalist Carmen; no matter how “experimental” it might be, it’s not a vision fully realized.

“The thing about opera is,” he said, “you get a lot of people working together to create this massive spectacle, and then it’s over. And all you have to take home with you is the experience.” The creation of such coordinated, ephemeral spectacles requires both serious committment and serious material resources.

The gilded age tradition of wealthy benefactors is clearly over. The very wealthy—now often nouveau riche and unbound to the trappings of aristocratic noblesse oblige—no longer consider themselves stewards of the sublime. As classical music scholar John Halle opined in “The Last Symphony” in Jacobin magazine, the upper and ascending classes no longer subject their children to the rigorous training necessary for classical musical scholarship. As Halle says, “today’s elite lacks the patience and culture for classical music.” Consequently, the patronage system has become rather passé, and even the odd anachronistic billionaire-funded ballet company might find itself dismissed on a whim. Put bluntly, the upper class just aren’t as classy as they used to be.

So too has public funding for high art taken a beating. While Americans might yearn for the sort of well-funded public arts programs they imagine Europeans prioritize, the reality is much bleaker. Despite Europe’s zealous emphasis on promoting a rich culture for a united continent, the European Union is constantly hacking away at centuries-old institutions in the name of belt-tightening.

But if the would-be private donors are now cretins, and public funding has been slashed to bits, who finances art today?

I first encountered the name Dakis Joannou while working as an arts and culture writer for a fun counterculture blog. Scouring the Internet for something subversive to cover for our “arty dirtbag” readership, I happened across a newly-published coffee table book, 1968: Radical Italian Design, which collected photos of a number of garish pieces of impractical-looking furniture. Since strange furniture always gets the clicks, the book made for a perfect post. It was doubly improved by the fact that the furniture in question was so unequivocally terrible.

Radical Italian Design was a bold avant-garde movement out of the late 1960’s that eschewed both form and function on principle, meaning the furniture it inspired is both intentionally garish and practically dysfunctional. The design philosophy is one of overt aesthetic and utilitarian offense—it is ugly, it is useless, and that is all on purpose, with none of the cheek that could even give it a campy appeal. I cannot stress this enough; it’s just terrible, ugly fucking furniture.

What interested me most, however, was that I had never heard of Radical Italian Design before. I’m no design expert, but I can at least distinguish a Verner Panton from an Eames, and I like to think I am passably aware of most of the significant stuff. I was also very familiar with the Memphis Group, another Italian design movement of slightly less offensive garish white elephants, once aptly described by The San Francisco Chronicle as “a shotgun wedding between Bauhaus and Fisher-Price.” But Memphis Group looks highly practical and understated in comparison to the Radical movement. How, then, I wondered, did this book about an unpleasant—but relatively minor—design movement come to be?

It turns out that every single piece of furniture photographed for 1968 belonged to one man: Dakis Joannou, a Greek-Cypriot billionaire, industrialist, hotel magnate, the largest importer of Coca-Cola in Europe and Africa, and one of the most famous art collectors in the world. 1968: Radical Italian Design is actually a project of the Athens-based Deste Foundation, Joannou’s arts non-profit, and an organization that conveniently allows him to monetize and promote his own personal art collection.

Deste has produced a rather extensive series of books advertising and legitimizing Joannou’s private collections. In 2012, for example, just as Greece began its descent into a dire humanitarian crisis, Joannou hosted a show of selections from his drawing collection at the Deste Foundation’s Project Space—a few months later, the show was made into a book. Joannou titled the show and subsequent anthology “Animal Spirits,” after the Keynesian economic term describing the “spontaneous urge to action, rather than inaction,” meaning the decisions we make that are borne of some primal human instinct, rather than measured or calculated reasoning.

If it seems like an arcane non-sequitur to name an art show for the uber-wealthy after an economic concept, consider it damage control. “Animal Spirits” actually ran as a substitute for an even ritzier art event of Joannou’s, in which 300 or so of his friends would travel to the vacation destination island of Hydra—the so-called “gem of the Saronic Gulf”—to party in opulence, and bask in the beauty, sun and art. The reason for the cancellation? The weekend coincided with the Greek elections. Even Joannou, generally insensitive to all matters of decency, admitted that going forward with the show would have been “inappropriate.”

Joannou is a big fan of the “Animal Spirits” idea, and the romance of such a mystical concept of rugged individualism guides his hand when it comes building his art collection. As Greece struggled to keep its people fed and housed, Joannou’s billions—which remained relatively untouched due to tax loopholes for the shipping industry—never quite trickled down to destitute Greeks, not to mention Greek cultural institutions.

In a glowing profile in Departures, a self-described “luxury” and “lifestyle” magazine, Joannou was quick to explain why “support isn’t helping anybody. In the beginning, a lot of people thought that’s what I was doing, and they would ask for funding for this or that. I said, ‘I’m sorry, I’m not into that.’ It’s about creating a platform.”

And who has Joannou given a platform to? As a collector of work from around the globe (though rarely, as many of his critics point out, Greek artists) he’s actually most famous for giving the world Jeff Koons, from whom he purchased the very first piece of his collection in 1985.

The now-famous sculpture was “One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank,” which Joannou purchased for for $2,700. The sculpture, best described as a basketball suspended in a glass fishtank, was a big break in the early days of Koons’s art career, not too long after he had left a career as a Wall Street commodities broker. Since then, of course, Koons has exploded into an infamous art superstar of sorts, even though his critical reception has been decidedly mixed—Nation art critic Arthur Danto described his work as “aesthetic terrorism.” Koons’s works have increased in both scale and price, with his massive metallic sculpture “Balloon Dog” raking in a cool $58.4 million. And who could blame Christie’s auction house for bidding so high? It’s big! It’s shiny! It looks like a balloon that has been twisted into the shape of a dog!

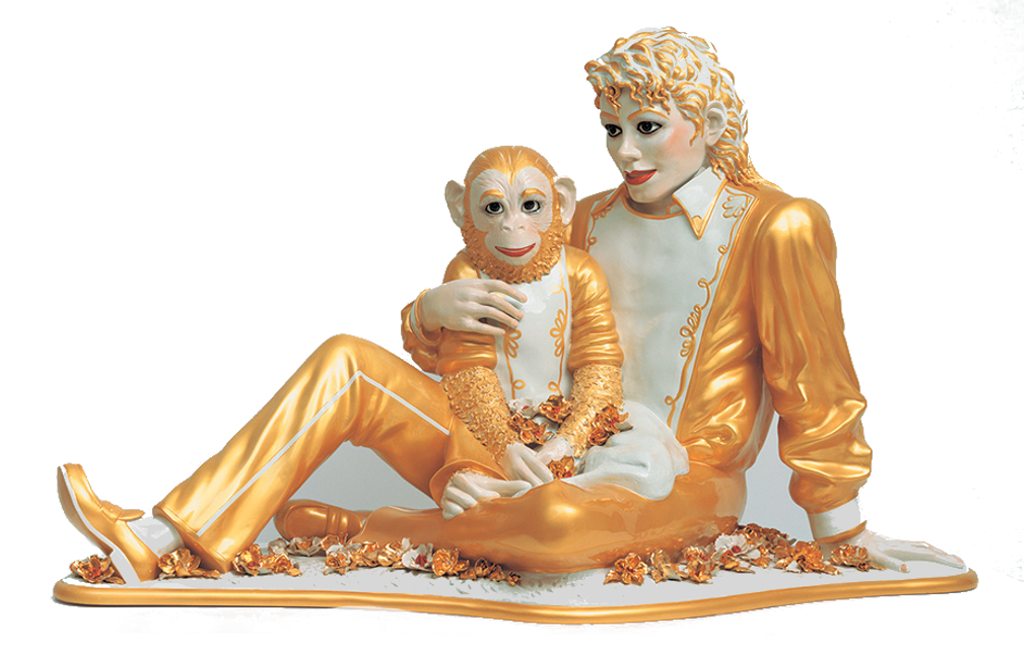

Koons was actually so possessive of this innovative idea that when one gallery began selling little balloon dog bookends in their gift shop, he sent them a cease and desist letter. Koons makes tchotchkes, but they’re art tchotchkes, and whether it’s a porcelain sculpture of Michael Jackson and his chimp Bubbles, or a series of inflatable toy Incredible Hulks adorned with bric-à-brac, everything he makes is immediately recognizable, insistently conspicuous, and totally unchallenging.

Now of course Koons and Joannou are dear friends, with Joannou facing scrutiny for charging Koons with curating a show of works pulled from Joannou’s collection at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, where Joannou is also a museum trustee. A public museum showing the private collection of one of the host muesuem’s own trustees would be enough to raise eyebrows, but Joannou handed the reigns over to Koons, his own prized pony, so to speak. The conflict of interest was glaring and extremely controversial, but the show went on. Wealth confers license to operate as one pleases, no matter how noisily one’s peers may register their ethical objections.

If that incident wasn’t incestuous enough, Koons also famously designed Joannou’s mega-yacht, The Guilty, which is quite possibly the ugliest boat in the world. The 115-foot long luxury liner is wrapped in a World War I British Naval camouflage called “Dazzle,” which was designed to evade enemy fire with a mish-mash of angular chaos. If you were to take a helicopter overhead, you’d see a massive mural of Iggy Pop on top, an artist whom Koons considers appropriately “Dionysian” for the setting. Ironically, Joannou has had to paper over the notorious “camouflage” of The Guilty, in order to disguise it from paparazzi. (Or perhaps to keep out design-enthusiast marauders?)

In a 2013 interview with Forbes, Joannou described the design concept thusly: “We did what we wanted; style was irrelevant. We designed a boat in an antistyle method. We have no rules, no programs, no plans.” The description echoes the ideological influence of Joannou’s own Italian Radical Design collection, which is, coincidentally, housed in the “living room” of the mega-yacht. The hideous is not to be spurned but embraced; style was irrelevant.

At first glance, Joannou’s collecting habits may seem like the eccentric vagaries of a an insanely wealthy magnate searching for legacy and legitimacy. I won’t deny the eccentricity charge, or the role of ego. One of Joannou’s beneficiaries, painter George Condo, has immortalized Joannou in surrealist portraiture. Another Deste favorite, sculptor Pawel Althamer, sculpted his dear friend Dakis as a Native American chief in full war bonnet, taking a cast of Joannou’s own face for accuracy.

But Chief Dakis’s project isn’t just bohemian wealth run amok, it’s explicitly ideological, the Animal Spirits of a man who fancies himself a Howard Roarke visionary, despite his total lack of credentials as a doyen.

And this is the state of fine arts under contemporary capitalism. Classics and antiquity have lost cultural cache in the age of disruption, and there is no longer an aristocratic imperative to support noble projects of lofty ambition. Today we’ve neither dutiful Kings, Vaticans, or robber barons to seduce the hoi polloi into complicity with visions of the transplendent. Nor do the experiments in democracy we deem “states” seem to be doing much better, having withdrawn much of the already measly funding available for highbrow cultural endeavors.

Even dictators don’t care to seem interested in bribing the proletariat with great works any more. Before being deposed, Moammar Gadhafi shelled out big bucks for private concerts from such virtuosos as Beyoncé and Mariah Carey. Despite intense criticism, Nicki Minaj took home $2 million last year to play for Angolan dictator José Eduardo dos Santos. And forget about the nouveaux riches investing in art for the people. Crooked pharmaceutical executive Martin Shkreli is despised for jacking up drug prices, but he is only slightly less despised for spending $2 million on the only existing pressing of a “secret” Wu-Tang Clan album and then threatening to destroy it.

So what we have now, if we’re lucky, is the odd production of Swan Lake (because it’s still good), a valiant but tragically austere Carmen (because it’s the best we can do), and Jeff Koons, because his work flatters Dakis Joannou’s vision of a Dionysian rebel.

For the new era of bourgeoisie, the symphony, the ballet, the opera and the museum hold less appeal than a pop star playing your private party, and they certainly can’t compete with holding court in an art empire of your own design. The ruling classes ain’t what they used to be, and vulgar narcissists like Joannou aren’t content with anything short of taking the products of their patronage home with them—and he does, all aboard The Guilty, bobbing atop his fugly floating Versailles.