What ‘Tintin’ Tells Us About Imperialism

Hergé’s comics are now infamous for their portrayals of colonized peoples, but they are useful artifacts for understanding the imperialist worldview.

In his examination of Christopher Nolan’s Batman movies, the late anthropologist David Graeber argues that superhero comics are essentially fascist. This analysis is based on the power relations involved: comics, Graeber says, represent an anarchic universe, where the only real laws are the ones created “on the basis of force.” He might have added that they also play a role in socialization. Comics teach budding members of society what to expect of the world outside their doors.

Growing up in an immigrant household, I missed out on the spandexed heroes that make up the canon of American adolescence. My first comics were The Adventures of Tintin stories. Until I was old enough for proper books, Tintin—the globetrotting reporter created in 1929 by the Belgian cartoonist Hergé—provided most of my knowledge of foreign cultures. When I was about 8, I remember scanning a world map, fruitlessly searching for the borders of fictional countries like Syldavia or San Theodoros.

Featured alongside his white terrier, Snowy, Tintin is one of the world’s most popular comic book characters, with more than 260 million copies sold in dozens of languages. Charles de Gaulle called Tintin his “only international rival,” and when I lived in Brussels, people spoke of Hergé as their own Walt Disney. (As a matter of fact, Hergé had quite a bit in common with Disney when it comes to prejudice, but we’ll get to that part later.)

Part of the appeal is that Tintin’s adventures are fairly realistic, at least by comic-book standards. There are no superpowers or silly costumes; Tintin’s antagonists are ordinary bad guys, like drug gangs and criminals. The character is frequently compared to Indiana Jones, but with less magic and mysticism. Steven Spielberg is also a fan, and he made a CG-animated Tintin movie in 2011.

In his essay on “Boys’ Weeklies,” George Orwell noted that the young-adult literature of his day tended to lean conservative. “[T]heir basic political assumptions are two,” he wrote. “Nothing ever changes, and foreigners are funny.” Something similar could be said of the Tintin comics, which contain most of the common tropes about foreigners and world politics. Before I ever heard the phrase “banana republic,” Tintin introduced me to San Theodoros, whose government is constantly being overthrown. My first awareness of totalitarianism came from “Taschism,” the state ideology of Borduria—where the Leader, aptly named Marshal Kûrvi-Tasch, elevated his whiskers into a national symbol.

Some of the depictions didn’t age so well. On rereading, I couldn’t help noticing that the comics’ Middle East is full of intemperate Arabs and that indigenous cultures are full of exotic tortures for travelers and their pets. When Tintin meets another European—whether a colonial officer, a merchant, or a lost explorer—it is usually a moment of relief.

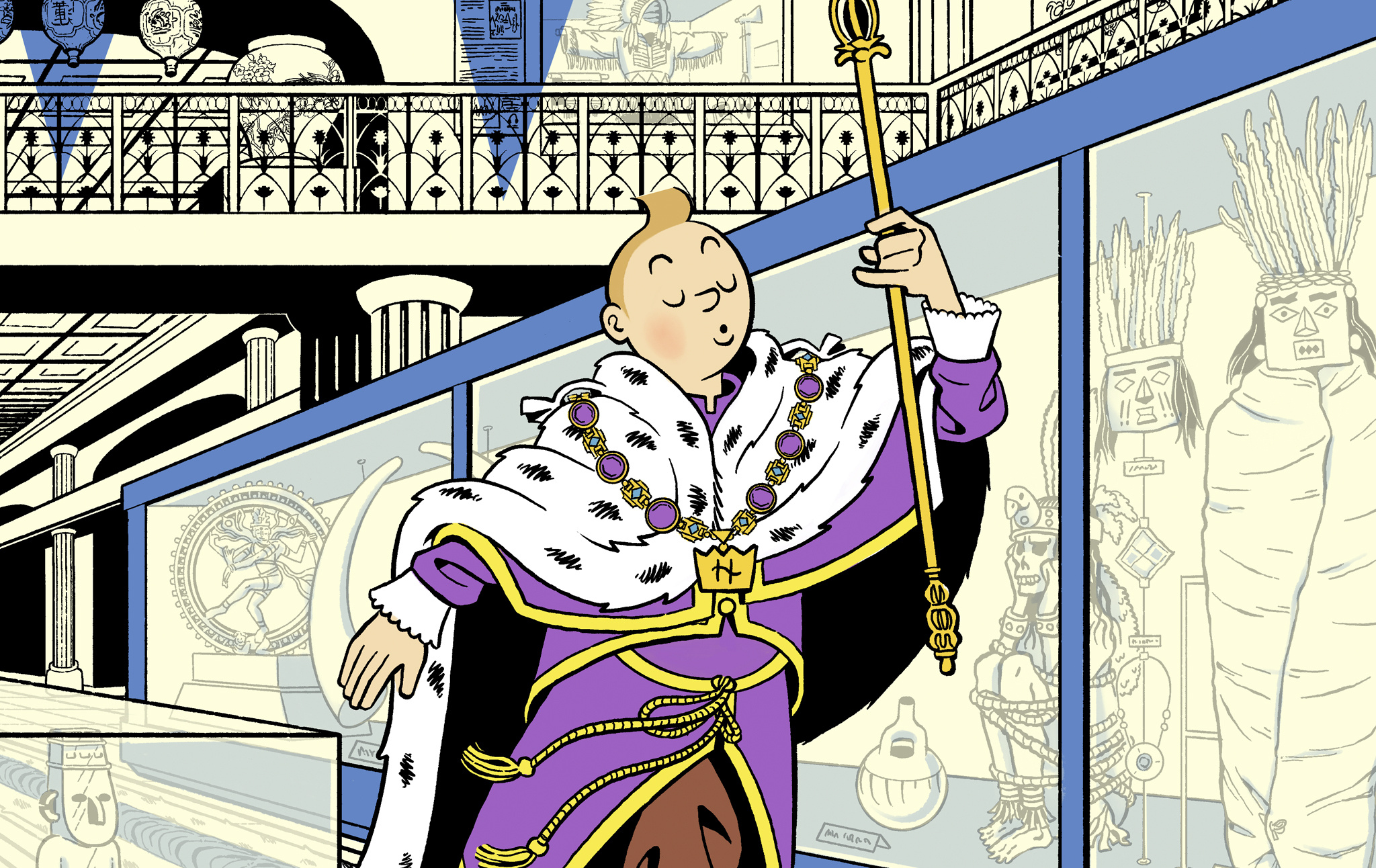

Indigenous animal (and human) cruelty is a recurring trope in early Tintin stories. Top: Cigars of the Pharaoh. Bottom: The Broken Ear.

As I worked my way through my parents’ collection, I came across one book that I had not been allowed to touch. Hidden away at the top of the bookshelf, Tintin au Congo—the series’ second-ever installment—was only available in indecipherable French. The story was even more incomprehensible: unlike the gentle animal lover from the later books, this version of Tintin spends most of his time skinning monkeys and harvesting ivory. When a rhinoceros gives too much trouble, he subdues the beast with dynamite. The natives in the story are thick-lipped spear-throwers who grovel before the hero and make his dog their new king.

The usual explanation is that Congo represented an embarrassing prelude to an otherwise stellar career—that Hergé was a “product of his times,” to use the modern euphemism. But that feels a little dissatisfying. While the racism in Congo is truly breathtaking, it’s hardly alone: imperialism is woven into the fabric of Tintin’s adventures, although it isn’t always so direct. Later stories replace pith-helmeted colonialism with cold-war logic as the hero gets entangled in the politics of now-independent countries. If Congo was a “product of the times,” it feels more authentic to say that the Tintin comics all were.

Most of the stories have been revised over the years, but you can still make out the contours of the 1930s peeking through modern editions. I don’t mean that the stories are meant as political commentary, although that was sometimes the case. More often, they simply show a world that Europeans expect to see: one where foreigners are cruel or helpless—and sometimes incapable of governing themselves, depending on the appropriate stereotype.

Tintin was created by Georges Remi (better known

by his pen name Hergé) for Le Petit Vingtième, the children’s supplement of the Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle. The Siècle was a Catholic newspaper, and it “was hostile to Communists, Jews, and Freemasons,” according to Hergé’s biographer Pierre Assouline, as well as “politics, the money-is-king outlook, the advent of mechanization, and modernism in general.”

As a monarchist, Hergé did not hesitate to lend his pen to conservative causes. Assouline describes a poster by Hergé, submitted for the 1932 elections, showing “a little girl praying at the foot of her bed while being stabbed by a Socialist in rags.” Another editor at the Siècle, Léon Degrelle, would go on to lead the fascist Rex party.

This gives you some sense of the character that will eventually emerge. Tintin is an upright stalwart for Christian values: he does not smoke or swear, shows no interest in women or alcohol, and spends a lot of his free time looking for the owners of lost wallets. His nemesis, the drug kingpin Rastapopoulos, is originally introduced as a movie director: a Hollywood elite if ever there was one.

Later adventures introduce Captain Haddock, an alcoholic with a vocabulary of esoteric curse words; the incompetent detectives Thomson and Thompson; and the half-deaf Professor Calculus, whose constant misunderstandings drive a large part of the series’ comedy. Around them are a rotating cast of gangsters, smugglers, kings, and mad scientists to keep the story moving.

Revisiting the series as an adult, I was surprised to learn that Tintin was not just a colonist, but an anti-communist as well. His first newspaper appearance in 1929 brought him to Moscow, where he foils a Bolshevik plot “to blow up all the capital cities of Europe with dynamite.” The story is crude even by propaganda standards: in it, Soviet factories burn hay to make smoke and clang on sheet metal to make the sounds of machinery.

From Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1929)

Tintin’s second appearance, in Congo, was meant to inculcate enthusiasm for the mission civilisatrice—otherwise known as European imperialism in Africa. The original was even worse than the one available today; a deleted scene shows Tintin teaching children at a missionary school about “your fatherland: Belgium!” In modern editions, he instead teaches simple arithmetic.

But I don’t want to linger too much on the earlier stories. Entire essays have been written on the racism in the Congo comic, which (like the animal trophies that Tintin hunts so judiciously) is a very easy target.

There’s better game to be had in the later stories. As a child, I sometimes wondered why the police in Morocco were French or why the educated classes in India were mostly British. But when Tintin went all the way to South America to retrieve a stolen idol, it seemed perfectly natural to return it to the European museum where it came from. Where else would tribal art belong?

The indigenous peoples that Tintin encounters in the early stories fit contemporary stereotypes: they are usually cruel, but superstitious and gullible enough that the young reporter can talk himself out of trouble. And while there may be local villains, it is usually a European or American mastermind pulling the strings.

That said, it’s hard to call Hergé a complete reactionary, since he does manage a few moments of sympathy for colonized people. Two instances in particular come to mind. After Congo, Tintin and Snowy land in the United States, where they’re caught in a strange hybrid of a gangster movie and a spaghetti western. Most of the story in Tintin in America revolves around a Native American reservation, where the tribe has been duped by a Chicago gangster. After Tintin escapes being used for target practice, the chase is interrupted by a gusher of oil. What follows is probably the darkest joke in the entire series: a group of businessmen crowd around Tintin, offering to pay him huge sums of money (“Fifty Gs!! A Hundred!!!”) for the land. When they discover that he doesn’t own it, they offer the Native Americans $25, then drive them out with bayonets.

From Tintin in America (1945 ed.)

Hergé’s sympathy for the Native Americans may seem surprising, given his earlier contempt for the Congolese. In this case, though, there is no contradiction: imperialism is perfectly capable of acknowledging the wrongs committed by other countries. (Keep this in mind the next time CNN condemns the Russian or Chinese governments for behavior that is routine for our own.)

On re-reading America, I noticed one more omission: there is not a single African American in the entire comic. Indeed, after Congo I could only find one important Black character in the entire series—or two if you count The Broken Ear, when the blond Tintin disguises himself in blackface.

This omission was not entirely Hergé’s fault. Early Tintins originally had a sprinkling of Black characters, but American publishers insisted on removing them—not because the drawings were offensive, but to protect innocent children from the dangers of race-mixing. Evidently systemic prejudices were at work, not just Hergé’s own.

There are a handful of unnamed Africans in The Red Sea Sharks, when the heroes rescue a shipload of Muslims being sold into slavery. This is about as close as we get to an apology for Congo, although it is a very insufficient one. Accusations of racism lingered, this time for the crude pidgin spoken by the rescued pilgrims. Once the slaves fulfill their role as victims in need of a white savior, they conveniently disappear offscreen.

Then there’s The Blue Lotus, where for once the role of imperialism features prominently. The story is set at the International Settlement, one of several foreign-ruled enclaves in Shanghai. Tintin witnesses the Mukden incident, a false-flag attack that was used to justify Japan’s 1931 invasion of China, and stops Western expats from brutalizing the Chinese locals. (One of the minor villains is an American businessman who is constantly losing his temper at Chinese servants between boasts of “our superb western civilization.”)

This is Hergé’s most sensitive work, and he even goes out of his way to poke fun at “stupid Europeans” who believe in stereotypes about Chinese people. But re-reading the story as an adult, I couldn’t help noticing how bug-faced the Japanese are drawn, or the slight condescension as Tintin explains racism to a Chinese orphan.

Scenes from The Blue Lotus (1936)

Still, The Blue Lotus is one of Tintin’s most popular appearances—not just for the historical background, but also the exquisite illustrations. The muse for both was Zhang Chongren, an artist studying in Brussels who introduced Hergé to Chinese art. One can’t help wondering why Hergé needed to make a Chinese friend in order to realize that racism and imperialism are bad. (If only he might have made a Congolese friend or two as well!)

Earlier I noted that the earliest Tintin strips appeared alongside newspaper columns that were not exactly progressive. Fascism was in vogue among conservatives, and the Vingtième Siècle frequently ran editorials praising Mussolini or complaining about the number of Yiddish-speaking refugees in Belgium. (Nowadays, many conservative Europeans say the same about Arabic.)

Hergé first approaches fascism in King Ottokar’s Sceptre, serialized from August 1938 to 1939. The comic is set in the imaginary kingdom of Syldavia, where Tintin uncovers a plot to annex the country to neighboring Borduria.

Sceptre puts Hergé’s monarchist values on display, showing readers a quaint, traditional peasant kingdom undermined by the machinations of a modern military state. The story appeared a year after the 1938 Anschluss, or annexation, of Austria and the Sudetenland by Germany, and in the same year that Italy invaded Albania. Just in case anyone missed those connections, Hergé spells it out in the name of the coup’s leader: Müsstler.

What strikes me on re-reading is how exactly Hergé got the blueprint of fascism, right down to the fifth column infecting the highest ranks of government. Many of the police and army captains are in on the conspiracy. That was a taste of things to come. A year after Tintin saved the Syldavian monarchy in the comics, the collapse of the real French army was blamed on the number of pro-fascist generals.

You might think King Ottokar’s Sceptre was a display of anti-fascist principles, but Hergé’s courage did not last. When Le Petit Vingtième closed, Tintin’s adventures reappeared in the pages of Le Soir, which had been seized and reopened under the control of Nazi Germany.

Hergé may not have been an active fascist, but he certainly collaborated with them and did well for himself under occupation. His comics brought new legitimacy to the stolen Le Soir, where they ran between antisemitic editorials and German war propaganda.

The next comic, The Shooting Star, fit the tone of the stolen newspaper very well. Here, the villain is a New York banker who uses his control of international commerce to foil the heroes in the race to find a fragment of a fallen meteor. The name of this sinister banker is—no joke—Blumenstein.

Prior to 1939, this might have been a simple case of bad taste, but it landed much worse for a country, and a publication, under Nazi rule. In late 1941, as the comet grazed the earth in the pages of Le Soir, Jewish Belgians were being fired from their jobs and placed under nighttime curfew. A week after the fictional Blumenstein was foiled, in May 1942, they were ordered to wear the yellow star. Deportations would start a few months later.

According to Hergé, this type of antisemitic caricature “was the style then,” which is about as convincing now as it was in 1945. He would later change Blumenstein’s name and nationality for reprints, in order to make the character less offensive. He was apparently unaware, though, that the new name—Bohlwinkel—was also a Jewish name, albeit an uncommon one.

Tintin’s first post-war adventure, The Land of Black Gold, brings him to the Middle East, an area where he had a “special affinity,” according to Tintinologist Michael Farr. From Morocco to Egypt, he spends more time in Arab cultures than any other destinations.

This story introduces 6-year-old Abdullah, a spoiled princeling who can be seen as a stand-in for the capricious oil-rich monarchies that have preoccupied Western diplomats ever since. For most of the 1950s, European foreign policy was focused on maintaining their preferred Abdullahs against a wave of nationalist revolutions.

In The Red Sea Sharks (which began serialization in 1956), Abdullah reappears, returning to live with Tintin after his father has been overthrown. The little terror is such a nightmare that Tintin immediately sets off to put the Emir back on the throne. Hergé was tapping into some deep anxieties: shortly after he started the story, French and British troops invaded Egypt to retake the Suez canal after Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized it. Charles de Gaulle, Tintin’s rival, would later come out of retirement in a futile effort to maintain French control of Algeria.

But back to 1950 for a moment. As a child, I found The Land of Black Gold difficult to follow: it starts with an oil crisis and ends in a fight between warring sheikhs with no clear distinction or motivation.

It turns out that there is a reason for this confusion. In the original serialization, Tintin does not travel to the fictional “Khemed,” but to Palestine, which was then under British control. After Tintin is arrested by the British, he is abducted by a Jewish terrorist group, who mistake him for one of their own, before he is again kidnapped by Arab rebels.

All of this would have made perfect sense to a reader in 1939. The Arab revolt against the British had just been suppressed, and even a Belgian schoolboy would have known of the Zionist colonial project. But the story halted with the start of World War II. By the time Hergé picked it up again, in 1948, Palestine as a legal entity no longer existed.

Scenes from The Land of Black Gold: 1950 (left) and 1971 (right).

That context has vanished from the modern version, or at least the editions available in English. When the story was revised in 1971, the British soldiers and Jewish partisans turned into Arabs; the warplanes flying overhead suddenly had Arab pilots, and even the Hebrew lettering in Haifa disappeared. Instead of a textured story about colonization, it became a senseless fight between Angry Arabs.

Come to think of it, that’s a pretty good metaphor for most Western reporting about the Middle East.

Most of these adventures take place at the fringes of European reach, but there are a handful of stories set in Latin America. Once again, the critique of imperialism is more forthright when the target is not European.

That introduces us to San Theodoros, the perfect representation of a country militarized for foreign capital. There, the government is both bloated and ineffective; almost everyone in the army seems to be a colonel. The two caudillos, General Alcazar and General Tapioca, are constantly overthrowing one another. At one point, Tintin faces the firing squad, but his execution is interrupted multiple times by news of a fresh coup.

But it wouldn’t be imperialism without a healthy dose of American capital, which materializes with the discovery of oil along the border with a nearby country. General American Oil offers Tintin a sizable bribe if he can persuade Alcazar to seize the oilfields.

I assumed this subplot was just Hergé being silly, but this is one of the more realistic moments in the comics. The “Gran Chapo war,” as Hergé calls it, was based on a brutal conflict over the Gran Chaco desert between 1932 and 1935. In that case, it was Standard Oil funding the Bolivian war effort, while Paraguay was backed by Shell. In an ending fitting of Hergé, the oil wells that they were fighting over turned out to be dry.

We could leave this here, as a satisfying pinprick at the reach of American capital. But Tintin returns to San Theodoros in Tintin and the Picaros—the twenty-third comic in the series, and the last one to be completed before Hergé’s death in 1983.

This time the stakes are higher. Alcazar has been overthrown yet again; Tapioca has instituted a Taschist regime, complete with security officers imported from Borduria. He has also arrested some of Tintin’s friends, accusing them of plotting a coup. The only answer is an outraged letter-writing campaign and a plea to the United Nations for clemency.

Just kidding. Tintin plans a CIA-style coup to overthrow the government.

The problem is that Alcazar’s guerrillas, who are hiding in the jungle, are too drunk to fight—and Tapioca is parachuting crates of whisky to keep the party going. Fortunately, Professor Buzzkill has a drug that makes the taste of alcohol intolerable. After sleeping off their hangovers, the now-sober guerrillas literally dance their way into the presidential palace and seize control.

Hergé wrote that he was inspired by Che Guevara, and one would be excused for thinking that Picaros is a coded reference to the revolutions in Latin America. But the analogy goes the wrong way: the Taschist government gets its support from Eastern Europe, while General Alcazar and his Picaros are backed by the International Banana Company. Created two years after the overthrow of Salvador Allende, the Picaros seem to have more in common with Pinochet.

This adventure taps into new reserves of cynicism that were not present in the early comics. Ever the dutiful boy scout, Tintin insists that no one is to be shot and refuses the colossal bribes that Alcazar offers for his help. But there is no discussion of elections or anything else that would improve the country; it is simply assumed that the General will resume power.

The final panel of Picaros shows the gang flying back to Europe, while armed police patrol the wretched favelas behind them. This seems like a fitting end to the story that started with a pith-helmeted colonist who brought the gift of arithmetic to the Belgian Congo.

It is tempting to think that Tintin left behind those colonial ideas, along with his pith helmet. But it’s more accurate to say that they evolved with the times, as European readers came to realize that their colonial subjects were not quite as grateful as they’d hoped. The overtly imperial trappings disappeared, but the plot remained the same.

Considering European and American foreign policy of the last two decades, there’s something painfully familiar about the dilemma that Tintin found himself in. Each new adventure came with a new excuse to insert himself into a world where he felt increasingly unwelcome. By the last page, the mask is off. There’s no longer any pretense of trying to help, as Tintin pulls off one last putsch before returning to his European home.