A Music Theorist on How White Supremacist Assumptions Have Shaped the Evaluation of Music

Professor Philip Ewell on how we decide what music is worthy of scholarly attention, and how to make music theory more welcoming for everyone.

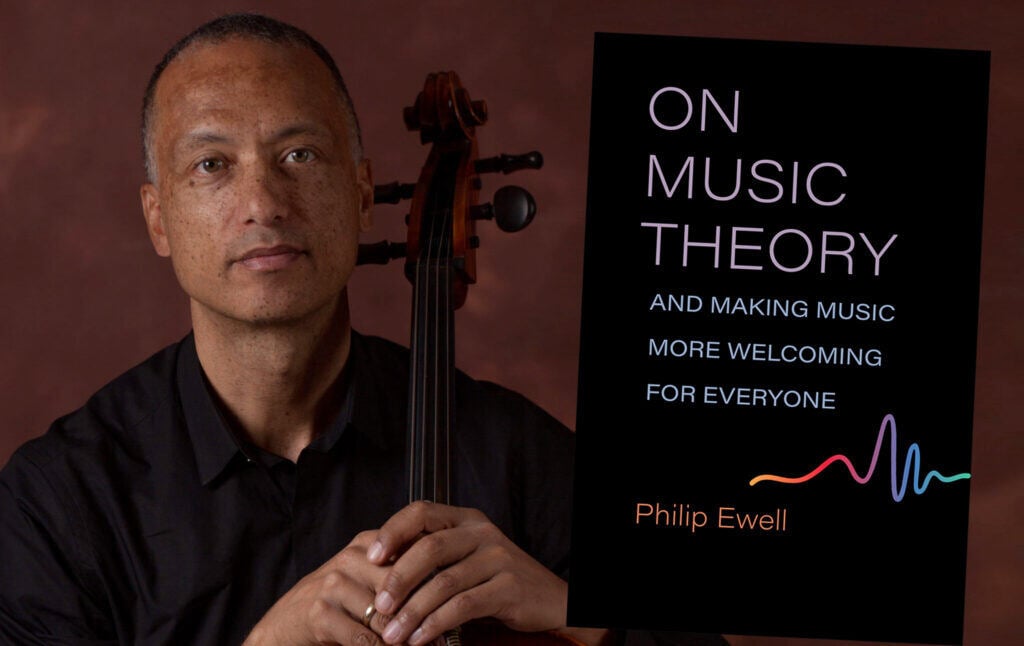

Philip Ewell is a professor of music theory and the author of the new book On Music Theory, and Making Music More Welcoming for Everyone(University of Michigan Press). Ewell is one of the most “controversial” music theorists in the country, having sparked a major controversy in his field by criticizing the “white racial frame” that dominates in music theory. Ewell argued that much of mainstream music theory has been build around unstated assumptions about which kinds of music are sophisticated/interesting/worthy of academic study. Today he joins to explain how the idea of white supremacy translated into normative conceptions about music, why it’s a mistake to think he’s trying to “cancel Bach,” and how music theory can be made, in the words of his title, more welcoming for everyone, meaning that it will break free of its narrow focus on a tiny group of European composers.

This conversation originally appeared on the Current Affairs podcast. It has been lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

Nathan J. Robinson

I thought I’d start by asking you for your reaction to an incident this year involving music and race. The longtime publisher of Rolling Stone was interviewed in the New York Times and made appalling comments. He had a book coming out, The Masters, where he interviews rock and rollers, and he picked eight white guys—Jagger, Richards, Dylan, etc.—and the interviewer asked him the quite basic question you might think he’d be ready for: why did you pick entirely white men? And he said, outright, that he did not think women or people of color were articulate or were “philosophers of rock.” Everyone was shocked by this, and he was immediately kicked out of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, where he’s had a prestigious position for a while.

But I thought that one person who would not have been shocked would be you. He articulated something that is rarely put that explicitly, but is implicit everywhere in music all the time.

Philip Ewell

Oh, my goodness. Yes, that’s exactly right. This is Jann Wenner, and I think he’s about in his mid-70s, and yes, a white cisgender man. What he said didn’t surprise me—you’re absolutely right, Nathan. From that generation, I often say that I have just a little bit of empathy. Rolling Stone and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame are icons of American popular music. Things are changing so quickly, and I have a little bit of empathy for folks like that. Things that were said 30–50 years ago don’t get said today, but underlying it was exactly the type of thing that I’m trying to expose with my work, which is this essentially white supremacist, patriarchal foundation on which we have built music and music education in the United States up to and including popular musics, as evidenced with this episode.

For him to say that, he’s just saying something that he actually believes. And more important, they think he’s saying something that a great many people of his generation actually believe, that the true philosophers of popular music could only be the Bob Dylans, the Mick Jaggers, and The Beatles, etc., and they just don’t want to look at themselves in the mirror and say to themselves they believe that because these people are white and male. That’s a bridge too far; it’s too painful to acknowledge the whiteness and maleness, but that’s really what’s going on there.

Robinson

I was just so fascinated by those comments. I thought: he probably has never even asked himself, why are these the people that I think of as the “masters,” the “philosophers”? What are my criteria that determine the exclusion of every non-white person from this category? I’m sure it’s never even crossed his mind. This process of canon formation is what I want to transition to and is kind of at the heart of your book: deciding who matters, what the serious music is, what the “art” is, and who’s worth talking about and studying.

Ewell

Nathan, you touched on something that’s so important: how is it that a person like that came to these decisions? Have they ever even asked themselves these key questions? My response is: how could they have 30 to 60 years ago? I’m 57 years old, and I rarely asked those questions. Why is it that in my own mind I believed somehow that these “great masters” of a so-called Western canon represented the best of the best?

Obviously, it was being taught to me at every step of the way. It was never questioned. I often say that this system of music and music education in the United States is a religion; it’s a faith-based belief system, just like other religions. You are simply told that you have to believe it, that you can’t doubt the system, that you have to have faith in the system, that it has your best interests in mind. Sound familiar? Sounds like a belief system to me. I’m a non-believer. And I think that it’s actually a really good analogy because my father was also an atheist, and he was Black—just in case, the listener or reader doesn’t know that—and by the way, I’m Black too. He hook, line, and sinker believed in the greatness of the Beethovens and the Shakespeares, and he himself, a Black cisgender man, never questioned why that was the case. That is just mind-boggling to me, but that’s part of the system.

Robinson

This is one of the most fascinating parts of your book. You write about your father and about this white racial frame that suggests that things that are European and white are better, and you point out that he had to a great degree internalized this. So, things that were associated with the refinement of Europe were the things that Black people ought to aspire to dominate and master. You write in the book that he was very proud when a Black person would excel in classical music, chess, or whatever it was. There was this implicit set of values of what constituted high culture, and he accepted that this was the high culture.

Ewell

Without question. He accepted it on faith. He was taught that at Morehouse College, where he graduated in 1948 with Martin Luther King Jr., by the way. And I would say in my father’s defense, he was just trying to survive in a virulently violent mid-20th century Jim Crow racism in the South. He was born in Louisiana and went to college in Georgia, so he lived in the South up through college. These were the things that all Black intellectuals of that era experienced, going back to Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois—this concept of the talented top 10th percent of Black people.

But let’s be clear, my dad did not admire those Blacks who rapped really well, or who played basketball really well, unless they were also social activist basketball players like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar or Bill Russell or others, then he found a way to let them into his heart. It had to be the Tiger Woods, the Serena Williams, the Jessye Norman on stage singing some German. And he never once questioned that all the people who created the greatness that he claimed to know so intimately were, in fact, white cisgender men, and they had to be because they’re the only ones who could advance to candidacy for greatness in a system built on whiteness and maleness. It makes perfect sense to me now. It took me only 57 years to figure this out, so I think I’m doing okay.

Robinson

Turning to your discipline of music theory, it strikes me that it in a certain sense, your basic thesis should seem simple and uncontroversial. Isn’t all music interesting and valuable? In the book, you give your definition of what music theory ought to be, and it’s something like “the study of all music.” But it’s incredible how, when you apply that and follow it through to its logical conclusion, so much of your field as it’s been constituted is just shattered by applying this framework: what would music theory look like if we adopted the presumption that all music is valuable and interesting?

Ewell

Exactly. It’s funny how people call me controversial—to bring it back to that—because the subtitle of my book is “making music more welcoming for everyone.” Oh, how controversial! Phil wants to make music welcoming? That crazy bastard! What on earth is going on, man?

No, seriously, for music theory, I often say that we play on the backside of the beat. On a rare occasion, that can be a good thing musically as a performer, but it’s usually a bad thing. “Get with the band and play on the beat, you’re making us look bad.” And music theory is, in fact, more than other academic disciplines within music, absolutely mired in this faith-based system. My book expresses, of course, a great deal of doubt and skepticism. I think I would cite Richard Taruskin, my departed colleague and a very famous musicologist who was a skeptic at heart—he often talked about that: if we’re not skeptical about what we’re doing, then what are we doing?

And that’s a really good point that I’d like to highlight to the listener and reader: when you accept somebody standing in front of you telling you that Brahms was the greatest composer who has ever lived, clearly they’re expressing an opinion. They want you to believe that it’s not an opinion, that it’s decided fact, that history and time itself has proven the greatness of Brahms. And they wouldn’t for a second think to question that, and they wouldn’t understand the structures and the power that people have when they play Brahms piano concertos or piano pieces, and the whole system that’s been handed down to us. In 1787, it’s not like 55 people got together in Philadelphia and represented this rainbow coalition of people: “We have the Cherokee delegation, and over here we have some Scottish folks, and half of the people are women.” No—they were white propertied men, many of whom owned people. Do you blame them for writing a playbook—the US Constitution—that benefited themselves? I’ll be honest, I probably would have done the same thing. I’m a human being, and don’t blame them for doing that. I just wish to highlight that represents the twin pillars of what we’ve done in this country: white supremacy and patriarchy. To sit there and think that music somehow is exempt from those twin pillars, that would be very silly indeed.

Robinson

I recall when I was reading your book, and when I was just listening to you, about how people see their ideologies as objective, factual truth. I actually once wrote a long article about the racist pseudo-scientist Charles Murray, who wrote a very interesting book, actually, called Human Accomplishment, where he tried to objectively tally human cultural accomplishments across the ages to prove that Europeans are superior. He said he was doing this scientifically and statistically, and the way he did this was by looking at encyclopedia entries: whichever continent has the most musicians with encyclopedia entries, they win the objective human cultural accomplishments. I don’t even think it crossed his mind who makes the encyclopedias!

Ewell

Well, it’s the great, great scientists! This is ironclad logic there, Nathan. Charles Murray: he’s like a modern day Joseph Arthur de Gobineau, who wrote the four volume essay on the inequality of human races. “I’m just calling balls and strikes here. I’m just putting out some objective knowledge and this is just how things are. It just turns out that white people are the coolest, the smartest, the dopest, the flyest. I’m just a scientist. I’m Hermes here. I’m just transmitting a message.”

This happened in music and music education in the early 20th century with the musical pseudo-scientist Carl Seashore. Julia Eklund Koza has a great book called Destined to Fail, and it unpacks some of the musicianship—a test—that he cooked up in his white supremacist mind. And I remember reading about one where he had like a sample set of 600 students, and lo and behold, there were only two Black students who could meet the bar. It’s just “objective” framing of musicianship and musical capabilities, and clearly the Black mind, our brains, are smaller—that’s what phrenologists proved with their little caliper things going around our skulls—so “we’re just pointing out the objective truth to the situation here.”

Robinson

I recalled Charles Murray’s Human Accomplishment because his explanation of what all the superior music is, and the objective human accomplishment in the field of music, maps on pretty well to mainstream music theory textbooks, which is what you go into in the book. I don’t know much about music theory, but we had a long piece in Current Affairs about it by an expert, and I read your book on it. It strikes me that your field is in many ways stuck in the 19th century and is close to phrenology in some ways.

Ewell

It is, it’s sad to say. We are losing some of those shackles, but you really have to look at folks who are under 40 years old. That’s unsurprising. The younger generations are less invested in the field as it has been passed down to us by a set of people who are, let’s say, white supremacist aligned or adjacent. No one’s donning a white hood and the cape here and lynching Negros or something like that, but the field itself is very far in the past.

The textbook analysis that my colleague Megan Lyons and I did uncovered that. 98-99% of the musical examples in there were written by white men. And then when you point that out, a few Black composers get dumped in there kind of like as an afterthought, rather than questioning the foundations of the field itself, which is what I’m doing. I like to question the foundations. I like to ask, why is it that the power has always rested in these people’s hands?

I could point out the simple fact that playing the piano is a requisite to being a music theorist under this scenario, and knowing some German is also a prerequisite. So, if you’re a great pianist and know German, you’re kind of already a music theorist, whether you know it or not. But that’s just one language of many, and just one instrument of many.

Of course, music theory from the mid to late 20th century would have us believe that they were by far and away the most important language and the most important instrument, and that is complete nonsense. It’s just nonsense. And anybody who tries to tell me that’s not nonsense and who gets unnerved by me saying that, I would just say that it’s gaslighting, frankly. It’s gaslighting that’s been gone on for just way too long—decades, if not centuries. It’s gaslighting, and it’s nonsense, and it’s time we move on from these things. Now, of course, my detractors will hasten to say, you will hate the music of Franz Schubert—you’re canceling Franz Schubert, Phil! Phil Ewell doesn’t play the piano! That’s what sour grapes will do. Fine. Haters gonna hate. That’s fine, I can handle that. Of course, anybody who reads more than three pages of my book would understand that—and I do not include John McWhorter in that because that’s probably about the number of pages John McWhorter wrote before he wrote his hit piece on me in the New York Times.

Robinson

Did he write about you? Oh, my God.

Ewell

Oh, yes, go and check out the hit piece by John McWhorter, to which I say: thanks, John, you just made me a ton of money. My book flew off the shelf after that piece. And more important than lining my pockets, he actually is helping me make my argument because it’s such a silly bit of drivel that he wrote that people in music are actually getting involved.

Getting back to the issue at hand here, it’s really important to realize that as it’s been handed down to us, there’s so much gaslighting and unquestioning of the nature of what we do, and it’s time we really start to unpack that. No, I don’t hate Schubert. No, I don’t hate Beethoven. I kind of like them. They’re good composers. But I just don’t think that they should be up on any hallowed hilltop because of our faith-based belief system that tells me that they’re on a hilltop and others are just below them in ranked hierarchies. That’s just silly. Shakespeare died in 1616, folks, and isn’t 400 years a good enough run for good old Billy Shakespeare? I think it’s time to let go of some of these things. People say, you have to go and see this new King Lear. Phil, it’s in a new staging. Of course it’s in a new staging! How else could you put up a new King Lear, for heaven’s sake! It was written 420 years ago!

Robinson

You pointed out, to the extent that arguments are made to support this conception of what the superior or sophisticated music is, they crumble under scrutiny. If you say, for example, that classical European music is the music we study because it’s sophisticated and complex, you come back and say: excuse me, jazz music? Why isn’t that at the center of music? If you’re going to have the hierarchy of complexity as the most interesting, you would have a totally different field if you apply that standard consistently. So, there’s no standard that you could apply that would get you to logically believe that it just so happens to be that all of the European composers are the best.

Ewell

Right. It’s impossible, really. Once you actually realize that the argument truly is based in whiteness and maleness—this idea of sophistication, civilization, complexity, complicatedness—and simply just accept that we were handed this as a bill of goods that was not truly what it claimed to be, then it becomes quite easy actually to realize that of course we segregated out jazz because at its core it is an African American musical genre. It needed to be segregated out just like African American people did. That’s very simple. That’s just called racial purity in a white supremacist system. So, just like people were segregated out, the musics needed to be segregated out too. And then, of course, you can trash jazz and everything. Finally, it gets let into the pantheon of greatness.

And then what happens? Well, the first thing is white men started to “discover” jazz in the ‘60s and ‘70s. The next thing is, they begin to play jazz. Of course, we all know the great jazz white male artists. Jazz has a very strong patriarchal element, and so there are very few women names. But of course, they were always there: Valerie Capers, Mary Lou Williams, Geri Allen—beautiful composers and musicians who were shunted to the side because they were women. Let jazz into our academies—what happens? White people take over because suddenly, it has some currency.

So, I’ve taught at three places, and they’ve all had great jazz departments, and out of about 15 different jazzers, I can remember one Black jazz person, and the other 14 were white. And no disrespect to these colleagues, some of whom are friends to this day—I simply wish to point out that jazz became white when it became academic, which is a very telling thing.

Robinson

For those of us who aren’t familiar with the curriculum of music theory and what music theorists study, your textbook analysis is very straightforward. You look at who are the composers that are included and excluded, and you provide a pretty knockdown demonstration that the field is racist just by going by who’s considered worthy of inclusion in the textbook.

But how is it, in more subtle ways, that what is presented as being interesting for music study, has kind of the same buried assumptions in it?

Ewell

I think that the best thing to look at probably would be musicianship requirements, and specifically piano proficiency requirements—music theory as it’s presented to undergraduates in the United States of America. Of course, it’s just presented as music studies. It’s not presented as the very narrow slice of Europe that it represents. Sometimes people say European, and that’s just entirely misleading. We’re talking about Vienna, Berlin, Paris, going back to Venice and a few more cities in Germany, like Leipzig or something like that. But we’re talking about not even 1 percent of the European continent, honestly. And, of course, we’re not talking about the musical traditions of the Roma, Arabs, Sami, Mongols, or Turks—the BIPOC people who’ve been there with their musical traditions, for centuries and millennia. In other words, there’s never been a time when there have been no BIPOC people or populations in Europe. That’s a fallacy. If somebody thinks that it’s just all white, that’s just silly.

But when people in the United States say “European” music, it’s really just a few places—German-speaking territories, prime among them—and we present it as the way we should think about music. And of course, the idea that pitch, the piano, and 12 tones in a system that emanated—to be blunt—from the Catholic Church is the system that represents all music, that’s kind of what we’ve been teaching. And, of course, colonization: you have to immediately think about the idea of presenting what were essentially white supremacists and patriarchal ideas across the globe in a colonial context. Of course, Christianity played a massive role.

I’m teaching Theory 1 currently, and to just look at all the music theory textbooks, literally last night I thought, Oh, my God, all of these hymns, all of these chorus, all these “Jesus, my pain and suffering”—there’s a lot of Christianity in the music theory textbooks, which I didn’t really dig into in my book. Maybe that’s the next project because that’s what we’re talking about: Catholic traditions morphing into German Protestant traditions of making music.

Of course, Bach was considered, by many music theorists, the first great composer. That’s nonsense, of course. But he was a very, very devout man. There was a period from 1717 to 1723 where he lived in Köthen and was employed by people other than the Church. That’s when he wrote his secular music—his solo violin partitas and sonatas, cello suites, the English suites, etc. So, for six years, he wrote non-sacred or secular music. For the rest of his life, he wrote Christian Lutheran music, and that has become the de facto type of studying music in the United States, and we present it to our students like it’s just music, and of course, it is not. It’s very, very narrow.

It’s based, in this case, in Christianity, whiteness, and maleness all wrapped together, and German and pianism—those are the core elements, and we present it to our students. It’s high time that we simply pull it down off that hallowed hilltop. Present it—I’m not saying “cancel” it. That’s just ridiculous when people say I want to cancel it. There’s no truth to that. I’ve never wanted to cancel anything, not even Heinrich Schenker—people say that I do. No, I wrote very explicitly that I don’t want to cancel him.

Robinson

No matter how many times you write, I still like these things to be taught, they’ll say, “he doesn’t want it to be taught anywhere in the country! He’s trying to purge the curriculum!”

Ewell

Exactly. It’s just going to be part of this nonsensical debate. And I don’t take part in those bad faith debates, I only take part in good faith discussions like the one we’re having here. The music education in the United States is a very narrow thing.

But I have to say, again, in defense of both music theory and academic music, it is changing quicker than I thought it would have five or six years ago. The paradigms are shifting, and we are getting a lot better. I don’t think it’s shifting fast enough for me, and I think my students—undergrad and graduate—would certainly agree with that. But it is changing and people are beginning to allow into their musical minds musics that are not based in a “Western tradition”—other musics, genres, peoples, races of musical peoples and other genders of musical peoples.

Robinson

Which has got to be more intellectually interesting for people who study music. It just massively opens the horizon of what the field can study and talk about and do, surely.

Ewell

Hear, hear. I remember one student at Oberlin interviewed me, a white man, a pianist. We got to this point, and he said, I’ve made some of these changes in my own mind, and it’s just been so liberating. And it was liberating for me to hear somebody say that because that’s something I’ve said.

This is rewarding work. It’s hard, arduous, and difficult. There’ll be pushed back. There are haters. But you do the work—it’s rewarding for yourself, but it’s also emancipating. It allows you to just open your mind. It’s not a matter of your tastes or your opinions, but you no longer have to think that this music is the pinnacle of musical humanity on planet Earth. That is emancipating. It’s absolute nonsense to actually believe that Chopin, Schubert, Schumann, Bach, Beethoven, Brahms—only about 15 or 20 men—actually are the pinnacle of musical thought, all leading to the greatness of Johannes Brahms, and when he died in 1897, all hell broke loose and everything just went to shit. Seriously, there are people who are still clinging to that.

And you know what? I try to be a little empathetic to people who cling to that because their worlds are coming apart. And I want to say to them, it doesn’t have to be like that. You learned how to play the piano; why don’t you learn how to play the erhu, or an oud, or something else? You’re a good musician. Do it. Just do something else.

Robinson

There’s a great YouTube video on this that quotes you a lot, and I can’t remember the creator’s name. But one of the things he does, once he shows his viewers the kind of buried assumptions about the superiority of a very narrow band of music, and he introduces someone talking about how music theory works in India with Indian music, and it’s so totally fascinating. You watch this and think, this just opens up a whole new way of listening and thinking.

Ewell

Absolutely. That was Adam Neely, and God bless him for that. He’s a really fine jazz bassist himself, and I think YouTube is where he actually makes his money because he’s got something like close to two million subscribers. And that’s why people actually recognize me on the street every now and then because that particular YouTube video has been seen over two million times.

But yes, it is exactly right that you can just bring in other cultures and their musics. And we, of course, have been obsessed with pitch and notes—C sharp and D natural—in our system, and that is often presented as proof of the superiority of the system. Total hogwash. There’s no truth to that whatsoever. And the one thing I think that’s also a little unnerving for folks is I have pretty good bona fides. I was a pretty damn good cello player back in the day, playing with a lot of great conductors and orchestras. I went through all the repertoire, all the cello stuff, and I have a PhD from Yale, which is a good school for music theory, with one of the best programs in the country. And so to have these criticisms come from within is a little something that took music theory by surprise, I think. I don’t think it should. I’m not actually a confrontational person. People might be surprised by that, but I can defend myself if I need to from a bunch of nonsense, and I can certainly block senders on my email account, which I do every other day.

Robinson

That does get us to your own disputes with others in the field, which are covered in this book. This even made the press because essentially, you, as I understand it, have been critiquing some of these foundational assumptions. You touched off a massive controversy through saying these things.

Ewell

Yes, that erupted in the summer of 2020, when this very bizarre journal issue of the Journal of Schenkerian Studies came out. I had no idea about it. They didn’t invite me to do anything. It wasn’t peer-reviewed. And yes, it kind of blew up because there was some very serious, aggressive anti-Blackness on the part of 10 authors—five authors, as I write in the book, were responding in good faith, but 10 authors were the core of the group. And apparently, Timothy Jackson led the charge. That’s what this panel found out. And yes, I just kind of went through those 10 “responses” in response to a nine minute spoken oral presentation, and then written in a very aggressive anti-Black tone.

I’ve said, I think on a podcast or two, that if I were a white person, it would have been an entirely different thing. And of course, people said, no—they want to not talk about race—and say, that’s not true and the would have been exactly the same, but I can actually prove it quite easily. No author could have written, Black people do this or Black people do that—kind of these crazy, insane responses where they’re talking about Black people—if it weren’t a Black person who had criticized, or let’s say challenged (they say attacked), music theory, and this was the response to this perceived attack on music theory and one of their sacred figures, Heinrich Schenker.

As I mentioned in the book, his is the only named music theory that’s routinely required for graduate students. It is, in fact, the way that we have been taught to understand music theory, and which is in American music theorists’ mind all of music. We’re gaslighted into thinking that it’s more than it actually is. That’s very much the way that we have learned to understand and interpret tonal music, and not just tonal music in a classical sense, but tonal music even all the way up to popular musics, which are quite tonal with tertian harmonies, and you can still have pieces in D minor and C sharp minor and things like that—keys of tonalities.

And absolutely Heinrich Schenker, who died in 1935 in Vienna, was a huge figure. He was very influential and great pianist. He edited all 32 sonatas of Beethoven. I’ve heard that his fingerings are quite hierarchical, unsurprisingly. He was the real deal. He was a repugnant person. He praised Adolf Hitler, hated everybody; he was an antisemite, anti-Black, anti-woman, you name it. I explained it all in the book. But he rose to prominence in the 1930s here in the United States. He had disciples, and that’s what took root.

And to be honest, people think that he had all the answers and that’s the way we should understand total music. I lived for seven years in Russia and I’m a fluent Russian speaker. They don’t study Schenker at all—never have. Schenker was an anti-Marxist, anti-communist, so it would have made no sense in the Soviet Union for him to be studied. The operable music theorist there was Hugo Riemann, for the initiated listener. So they don’t study tonal music in the same way yet they in the Soviet Union, and frankly, in almost all the European countries where some of these traditions come from, don’t study Heinrich Schenker.

Because of American influence, they know a little bit more about it, and certainly in England, you can take classes in Schenkerian analysis. He’s one of these saintly figures, and yes, absolutely, he was extremely racist and sexist. In fact, he’s the only person I’ve ever called a racist in my very voluminous writings about all of this now. I actually did call him a racist. And they say, how dare you? Did you see what he wrote? It was really awful: cannibal Africans; you shouldn’t intermarry races; interbreeding racism, don’t do it; Jews are the greatest threat to Germany, and he himself was Jewish, so he was an antisemite Jew who died in 1935.

It’s just incredible how they reacted. I actually referred to this once as a “stand your ground” academic reaction. Stand Your Ground laws in the United States, as you know, were cooked up, essentially, to protect white people during an unhinged white reaction to a falsely perceived threat from Blackness. I’ll say that again: Stand Your Ground laws exist to protect unhinged reaction of whiteness, to a falsely perceived threat, from Blackness. With Stand Your Ground laws, when a white person shoots the Black person dead, they’re going to get off because they’ll say the Black person was threatening them, and it was a big Black guy and was very threatening, and then the jury will say that they were just protecting themselves.

So, “stand your ground,” and you’re free to go. But I say in response to the “stand your ground” academic response to my nine minutes of speaking maybe 900 words about a really disgusting person, Heinrich Schenker, no guns were discharged. We’re not litigating this in the state of Florida, so they lost. But one last time, I’ll say what Volume 12 of the Journal of Schenkerian Studies represented was an unhinged reaction of whiteness to a falsely perceived threat from Blackness. That’s exactly what happened.

Robinson

For those of us outside music theory, like our listeners and readers, we may not be familiar with this Heinrich Schenker. Although, when a writer wrote about your controversy for Current Affairs—he was at a PhD music theory program—he said he had to take two seminars solely on Schenker’s theory. So, this guy has been a big deal for a while.

You are a teacher as well as a theorist, so you must have thought a lot about how to teach music theory better. You are dealing with the set of textbooks that you’ve got, and you have tried to figure out what is a different, better approach that makes music welcoming for everyone. So, I want to ask you a little bit about how you managed to do that, or what you think a better teaching of music theory would look like. Because you make it clear in the book that it is not just by percentages of inclusion in the textbooks until they mirror the population.

Ewell

Correct, that’s a good one. I would open by saying that I am co-authoring an undergraduate music theory textbook with two other authors, Rosa Abrahams and Cora Palfy, contracted with W.W. Norton, and hopefully by a year from now we’ll have something out there. So, this is something that I’ve thought about a lot with my co-authors. We have meetings weekly on Zoom and talk about all of these things, and it is hard. It’s hard to, kind of from the ground up, build a new idea of what music theory is, and then present it in a pedagogical fashion.

But some of the highlights: we have an editorial board with people who are experts in other types of music, like some with Indonesian Gamelan and someone with Hindustani north Indian ragas and rhythmic cycles. We have a jazz expert, and we have an expert on Tanbur. We have a chapter titled simply “The Blues,” because the Blues is just so huge in the American musical lineage. Rock and Roll is rhythm and blues put together, basically.

We still have examples of people like Bach and Beethoven, but instead of having 50% of the book, representing maybe two or three composers—that would be Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, probably—they’re going to represent 2% of our book in total. In other words, we have many different composers and genres. And there are some global traditions as I’ve just mentioned, but that’s actually very difficult because you can’t in two or three or four semesters of music theory present all the world’s music—obviously, that’s just way too much.

So you have to make choices. Before, the choice was easy, actually, because we were taught that there were only about 15 great composers who ever lived ever so you just have to choose what Chopin example you’re going to use. Which example by Schumann—Robert not Clara; you had to have Robert because he was a man. Let’s leave Clara Schumann out of this because she couldn’t be at the top of the hilltop. She was one rung below; therefore, her music, which is absolutely gorgeous, couldn’t exist because she was a woman.

All of that nonsense is gone in our textbook. I mean no disrespect to those who’ve written music theory textbooks before us. I think that even many of those authors, many of whom are still alive, would actually agree that the books were rooted in white supremacy and patriarchy and that we need to do better for our students. It is a great disservice to our students if they are taught music in a late 20th century mindset in 2023. It shouldn’t happen, and I hope to change that.

Robinson

There are really strong elements of individualism in this too: the idea that it’s the genius composer who makes the good music, not a culture.

Ewell

The great man theory. Exactly. There’s absolutely that element of individualism, but I have to say—and I’m sure you know this—that’s kind of antiquated. People are now questioning objectivity and the great man theory. You can actually talk about the bad things about Thomas Jefferson, in addition to the good things. Of course, there’s a great backlash to that, because there are tens of millions of Americans who say that you can’t talk about the bad things about Thomas Jefferson. Well, I can, I will, and I do, but we’re having those debates now, whereas 20 years ago, there was no debate surrounding whether you could talk about how anti-Black and horrible Thomas Jefferson was on the one hand, along with his extremely influential documents that he wrote on the other, both of which happened. We should present all of that to our students the same way we should present all the horrors of Heinrich Schenker to our graduate students. It’s the same thing.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.