Jimmy Carter Stood up for Palestinians. Why Won’t Today’s Democrats?

At the height of George W. Bush’s War on Terror, Jimmy Carter had the courage to call out Israel for its human rights abuses. What’s stopping Democrats from doing the same now?

As Jimmy Carter celebrated his 99th birthday early last month, media coverage showed that a certain consensus has formed around the former president. He may have been a somewhat ineffectual leader, plagued by raging inflation and the Iran hostage crisis—a president “overwhelmed by forces that he was unable to control,” as William Galston of the Brookings Institution put it in a recent retrospective. But as an ex-president, he’s seen as a thoroughly decent guy. For many years, he donned a hard hat and built Habitat for Humanity houses with his own hands. He worked to stop nasty parasitic diseases in Africa and taught Sunday school at his little hometown church in Plains, Georgia, where his neighbors seem to adore him. In 2017, Corey Robin wrote in Jacobin that Carter has “acquired a kind of saintly halo about him,” and this seems about right. In the public consciousness, Carter has become a sort of national grandfather figure—charming, benevolent, and above all, uncontroversial.

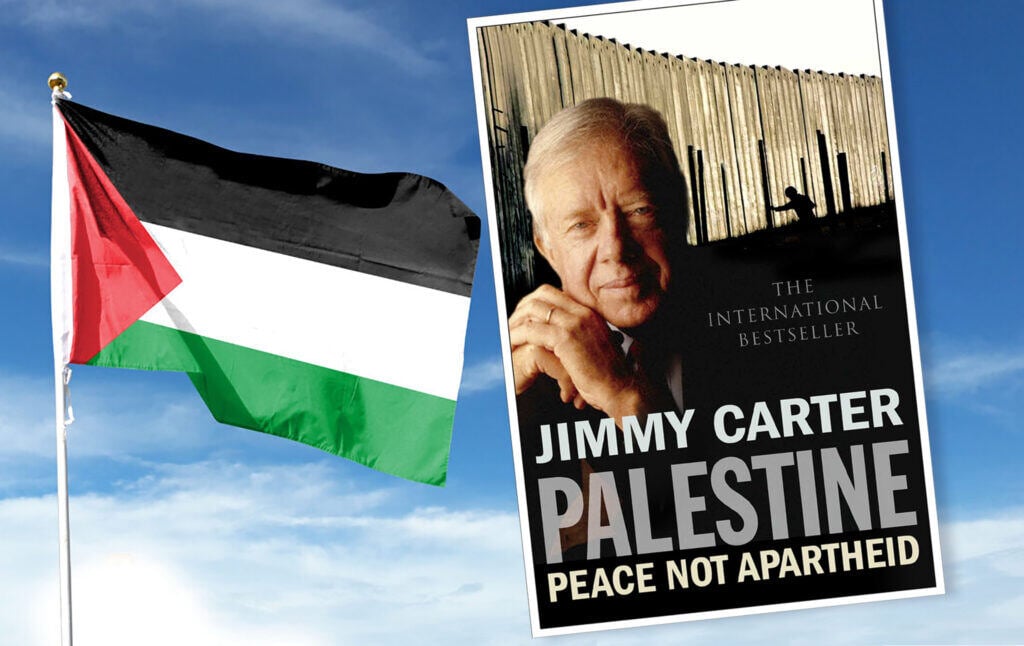

This kindly-old-man image does Carter a disservice, though. It leaves out one of the most important parts of his long career: namely, his vocal support for Palestinian human rights and his willingness to criticize the state of Israel for its violations of those rights. Nowhere in the New York Times’ birthday profile, or the Guardian’s, or CNN’s, will you even find the words “Israel” or “Palestine.” But it’s an area Carter has been concerned with for decades, and one where he has shown real moral courage and refused to back down in the face of strong opposition. Nowhere is this courage more apparent than with the publication of his 2006 book Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid.

Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid is an unusual book, one that defies genre categories. Part memoir, part history, and part geopolitical analysis, it opens with an account of Carter’s first visit to Israel in 1973, a few years before he became president. A guest of then-General, soon-to-be Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, Carter sees a selection of famous tourist sites—the Mount of Olives, the Sea of Galilee, Bethlehem, and others that hold spiritual significance for him as a Christian. He recalls being impressed by the “pioneer spirit” and “quiet dedication” of Israeli farmers in the country’s kibbutzim, or communal settlements. But at the same time, he’s troubled by the displacement of Palestinians from the sites he’s visiting, which he compares to the U.S. government’s treatment of Native Americans in his home state:

[I] equated the ejection of Palestinians from their previous homes within the State of Israel to the forcing of Lower Creek Indians from the Georgia land where our family farm was now located; they had been moved west to Oklahoma on the “Trail of Tears” to make room for our white ancestors. In this most recent case, although equally harsh, the taking of land had been ordained by the international community through an official decision of the United Nations.

This is a remarkable thing for a former U.S. president to say. The comparison between Palestinians and Native Americans is imperfect, but it’s one both groups have made in the past; most recently, members of the Diné (or Navajo) people called on their tribal leadership to show support for Palestinians under Israeli bombardment in Gaza, saying that a “history of occupation and settler-colonialism ties Diné and Palestinian people together.” The United States and its leaders, though, have always been reluctant to acknowledge that history, to the extent that the U.S. boycotted a United Nations event that commemorated the 75th anniversary of the 1948 Nakba earlier this year. Carter’s writing breaks with this taboo, showing an awareness that the core issues in the Israel-Palestine conflict are indeed ones of colonialism, forced migration, and even ethnic cleansing.

Beyond the roots of the crisis, Carter is also visibly horrified by the living conditions Israel imposes on Palestinians in the Occupied Territories. Reflecting on the landmark Camp David Accords, he states bluntly that “important provisions of our agreement have not been honored since I left office,” since “the Israelis have never granted any appreciable autonomy to the Palestinians.” Again, this is something everyone in Washington knows, but few will actually admit, let alone criticize. In one chapter of his book (set immediately post-presidency, in the early 1980s), Carter and his wife Rosalynn visit both the West Bank and Gaza and spend days speaking to ordinary Palestinians about their lives. In one firsthand account after another, their hosts tell them about the inhumane treatment they receive from Israeli security forces, who restrict even their emergency medical care:

Rosalynn visited the largest hospital in Gaza, and the doctors told her that they had great difficulty providing transportation for critically ill patients. They showed her a row of ambulances that had been contributed by a European nation and said that they couldn’t be used. He claimed that Israeli officials refused to issue license plates because the chassis were twelve inches too long.

Beyond being simply abusive, the occupation forces are often downright petty:

We learned that after one of [our hosts’] sons recently had made a statement critical of the Israeli occupation, five of the father’s truckloads of oranges had been held up at the Allenby Bridge crossing into Jordan for several days—until the fruit had rotted. This was a large portion of their total crop for the year.

Any form of protest against the ongoing mistreatment, meanwhile, is severely repressed:

[E]ven minor expressions of displeasure brought the most severe punishment from the military authorities. They claimed that their people were arrested and held without trial for extended periods, some tortured in attempts to force confessions, a number executed, and their trials often held with their accusers acting as judges.

Notice the reference to torture, which was perfectly legal under Israeli law until 1999—and which, as Mohammed el-Kurd writes for the Nation, Israel still finds excuses to use against Palestinians today. There’s an obvious double standard at work here. When a country like China or Venezuela commits human rights abuses like the ones Carter describes, the U.S. gets up on a soapbox and condemns them, often following up with devastating economic sanctions. But when it’s an official ally like Israel or Saudi Arabia, they get a free pass along with billions of dollars in military aid to continue what they’re doing. It’s rare for politicians to apply their principles consistently, demonstrating a genuine commitment to human rights rather than repeating hollow pieces of rhetoric. With Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, Carter does just that. Perhaps it’s because, strictly speaking, he’s not a politician anymore.

In the English language, there is a word for conditions like the ones the Carters witnessed in Palestine—a status quo in which one group of people keeps another group penned up in a particular area, with armed guards and a network of checkpoints, and refuses to let them move, assemble, or express themselves freely. The word is “apartheid,” and unlike so many commentators in the United States and Europe, Jimmy Carter isn’t afraid to use it to describe Israel. In a chapter devoted to the construction of the separating wall around the West Bank, he makes the issue explicit:

Israeli leaders have embarked on a series of unilateral decisions, bypassing both Washington and the Palestinians. Their presumption is that an encircling barrier will finally resolve the Palestinian problem. Utilizing their military and political dominance, they are imposing a system of partial withdrawal, encapsulation, and apartheid on the Muslim and Christian citizens of the occupied territories.

And again, in the summary section that concludes the book:

A system of apartheid, with two peoples occupying the same land but completely separated from each other, with Israelis totally dominant and suppressing violence by depriving Palestinians of their basic human rights. This is the policy now being followed….

If anything, Carter shows an excess of caution. He qualifies the first statement, writing that while Israel practices apartheid, the “driving purpose” behind it is “unlike that in South Africa—not racism, but the acquisition of land.” But it’s hard to see how the two can be separated, since we’re talking about the “acquisition” of territory from a particular ethnic group by forceful dispossession. Certainly the rhetoric of Israel’s political leadership has been consistently racist, calling Palestinians “wild beasts” (Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, 2016) and saying that “like animals, they aren’t human” (Defense Minister Eli Ben Dahan, 2013). It’s a strange caveat to include.

This quibble aside, though, the use of the word “apartheid” is the single most striking thing about Carter’s book. If you’ve read things like Norman Finkelstein’s Gaza: An Inquest into its Martyrdom or Noam Chomsky’s Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinians, there’s nothing particularly groundbreaking about the book’s content. In fact, you might describe Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid as Diet Chomsky. But authors like Chomsky and Finkelstein can be rendered marginal in the public eye, their works dismissed as far-left crankery. This is more difficult with Jimmy Carter. In the first place, his actual political record is centrist, maybe even center-right; he’s the president who ushered in the age of deregulation and privatization in the United States. He’s hardly a radical by anyone’s reckoning. He also has the weight of experience on his side, having personally met and negotiated with almost every major figure involved in the Israel-Palestine conflict, from Golda Meir to Yasir Arafat. So when he says that Israel practices apartheid in the West Bank and Gaza, it can’t be dismissed as the shallow understanding of someone unfamiliar with the topic. In more recent years, leading humanitarian organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and even the Israeli B’Tselem have begun to use the “apartheid” label, as have Israeli journalists like Benjamin Pogrund, who wrote a memorable editorial for Haaretz in August 2023: “For Decades, I Defended Israel From Claims of Apartheid. I No Longer Can.” In acknowledging the reality on the ground, and calling it out for what it clearly is, Carter was more than a decade ahead of his time.

Back in 2006, though, a lot of people didn’t see it that way. Almost immediately after the book was published, Carter received a barrage of criticism over its contents, both from conservatives and people ostensibly to his left. In the Democratic Party, Howard Dean—then the DNC national chair—took it upon himself to issue a public statement, saying that “While I have tremendous respect for former President Carter, I fundamentally disagree and do not support his analysis of Israel and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” and promising that “I and other Democrats will continue to stand with Israel.” Nancy Pelosi joined in, saying that “It is wrong to suggest that the Jewish people would support a government in Israel or anywhere else that institutionalizes ethnically based oppression, and Democrats reject that allegation vigorously.” (Virtually every good idea of the last 50 years has been “vigorously denounced” by Nancy Pelosi.) Michigan representative John Conyers even asked Carter to change the book’s title. Notably, though, none of these elected officials deigned to address the substance of Carter’s arguments, or attempt to show that he was wrong about the issue of apartheid. They simply condemned him for broaching the subject at all.

Nobody was more outraged, though, than Alan Dershowitz. Sooner or later, everyone who expresses a serious concern about Israel’s treatment of Palestinians runs up against Dershowitz, and Carter was no exception. When Carter appeared at Brandeis University to discuss his book, Dershowitz told Reuters that he would “have my hand up the minute he finishes” to challenge him. In fact, he ended up delivering his own lengthy rebuttal talk afterward, in which—as recounted in Dershowitz’s 2008 book The Case Against Israel’s Enemies—he accused Carter of “having become an advocate for the maximalist Palestinian view, rather than a broker for peace.” Objecting specifically to the word “apartheid,” Dershowitz claims in his book that Carter’s use of the term implies “that Israel is illegitimate, racist, and deserving of destruction,” and serves “to strike at the foundations of the state itself.” This is a common rhetorical trick, equating criticism of specific Israeli policies—the construction of separating walls and illegal settlements, the checkpoint system, the restrictions on food and medical supplies coming into Palestinian territory, and so on—with a wholesale rejection of Israel’s much-vaunted right to exist, and a tacit desire for violence (or “destruction”) against Israelis. Of course, Carter said no such thing; Dershowitz is simply putting words into his mouth. He goes on to recount a concert he attended in Jerusalem “with an orchestra composed of Israelis and Palestinians” and a similarly diverse audience, using this as evidence that Israel is not an apartheid state in the way South Africa once was. This is disingenuous and irrelevant, because Carter’s argument is specifically that apartheid is practiced in the Occupied Territories, not Israel proper. Concluding the relevant chapter of The Case Against Israel’s Enemies, Dershowitz dips into the territory of personal insult, saying that “Jimmy Carter’s recent descent into the gutter of bigotry” means that “history will not judge him kindly.” Harsh stuff, to say the least.

With all this blowback, it would have been easy for Carter to simply walk back his arguments, apologize for them, and move on. This is the standard move for political figures in his position. As recently as July 2023, for instance, Representative Pramila Jayapal apologized for referring to Israel as a “racist state,” a phrase more than 40 of her fellow Democrats condemned as “unacceptable”. There can be strategic reasons for making such an apology, and there’s certainly a difference between a sitting politician like Jayapal, who has to worry about reelection, and a retired one like Carter. Carter’s privilege as a white man matters, too. Still, it’s striking that Carter responded to the controversy about the word “apartheid” in exactly the opposite way. When challenged by NPR interviewer Steve Inskeep, he wouldn’t give an inch:

Inskeep

Mr. President, perhaps I could begin with the title of your book, which has caused a bit of debate. Could you just make, briefly, the best case you can for why “apartheid” is the best word to use?

Carter

Well, I’ll try to make a perfect case. Apartheid is a word that is an accurate description of what has been going on in the West Bank, and it’s based on the desire or avarice of a minority of Israelis for Palestinian land. It’s not based on racism. Those caveats are clearly made in the book. This is a word that’s a very accurate description of the forced separation within the West Bank of Israelis from Palestinians and the total domination and oppression of Palestinians by the dominant Israeli military.

Again, there’s the strange qualifier about Israel’s alleged non-racism, but the charge of apartheid is very much intact, and there’s no apology. This could be a textbook example of how not to give in to a pressure campaign. It cost Carter, too. As NPR notes, 14 members of the Carter Center, his nonprofit organization, resigned in protest against Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid. He still stuck by his principles.

So why is a controversy about a book from 2006 relevant today? Well, the answer should be fairly obvious: because Israel is currently waging indiscriminate slaughter in Gaza, and we will all be judged by how we respond. As the main left-of-center political faction in the United States, the Democratic Party might be expected to care about the human rights of Palestinian civilians, and to urge an immediate halt to the violence, but this has not happened. Instead, the Biden Administration has condemned calls for a ceasefire as “repugnant,” and Secretary of State Antony Blinken has promised that Israel will “always have the support of the United States,” even as the bombs continue to fall. With a few notable exceptions, like Representatives Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib, Congressional Democrats have fallen in line.

The whole grim spectacle puts me in mind of a question Johnny Cash once asked, when radio stations refused to play his “Bitter Tears,” a concept album about the injustices suffered by Native Americans. “Where are your guts?”, Cash demanded, and we might ask the same of the so-called leaders in today’s Democratic party. It’s easy to side with the more powerful party in a conflict, to simply go with the flow—and in case after case, Democrats have done just that. Pennsylvania Senator John Fetterman, someone I voted for in 2022, has rattled off a series of truly wretched Israel takes, saying that it’s “reprehensible” that anyone would write “Free Palestine” on a wall in Pittsburgh, and claiming—with a straight face—that “They are not targeting civilians. They never have, they never will” when asked about the IDF. (A few days before Fetterman said this, the IDF targeted and destroyed Gaza’s Kamel Ajour bakery, which many of the surviving civilians relied on for food. Perhaps the Senator thinks it was a tactical assault bakery.) Twenty-two particularly craven Democrats have just voted for a resolution to censure Rashida Tlaib—the only Palestinian-American in Congress, and someone who has family in the West Bank—over her criticism of Israel. Hakeem Jeffries, the House Minority Leader, has called Israel’s bombing campaign a “necessary and urgent project for it to complete,” while New York’s Ritchie Torres boasts to Politico that there are “few people in American politics who have been as visibly and vocally supportive of Israel as I’ve been.” Even Bernie Sanders has chosen to shovel dirt on his legacy, refusing to call for a ceasefire and opting for the nonsense half-measure of a “humanitarian pause” instead. Too few, it seems, are willing to stand up and state the obvious: that the bombing is an atrocity, and it must stop.

Jimmy Carter isn’t some uniquely admirable figure. Far from it. But in 2006, at the height of the Bush administration and the War on Terror, he had the courage to call out the state of Israel for its human rights abuses and stand up for a Palestinian population that could offer him nothing in return. He did it because he believed it was right—no more, no less. As the corpses pile up in Gaza, today’s Democrats would do well to look to their elder statesman and learn a little something from him.

If Jimmy could do it, what’s stopping them?