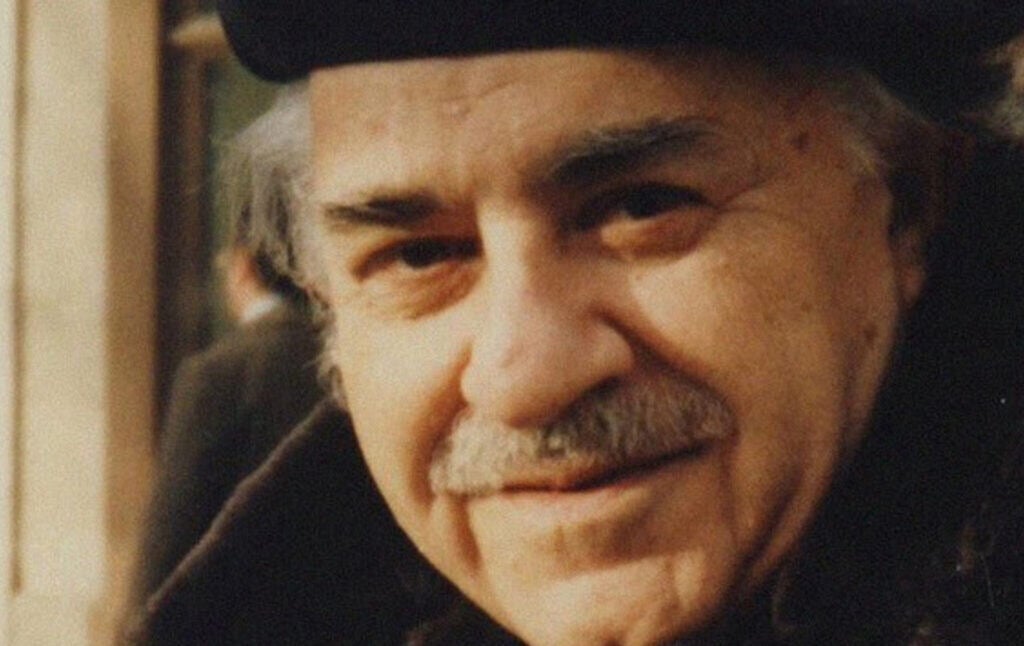

Introducing Murray Bookchin, the Extraordinary Originator of ‘Social Ecology’

Biographer Janet Biehl explains why the late thinker’s decentralized, anti-capitalist, ecological vision remains so important today.

Janet Biehl is one of the leading libertarian socialist writers in the country. For several decades, she was the partner and collaborator of the late political theorist Murray Bookchin, who stood, in the words of the Village Voice, “at the pinnacle of the genre of utopian social criticism.” In bracing works like “Listen, Marxist!” and The Ecology of Freedom, Bookchin laid out the basis for an anti-capitalist, ecologically-oriented, and anti-authoritarian left. Bookchin’s analysis was often provocative, and in works like “Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism” and “Re-Enchanting Humanity” (which includes a satisfying takedown of Richard Dawkins) he challenged what he felt were the dangerous currents of anti-rationalist and primitivist thinking emerging on the left. Bookchin tried to forge a philosophy that was pro-technology while sensitive to ecological destruction, and which salvaged insights from Marx while avoiding the rigidities of 21st century Marxism. He was one of the first thinkers to warn that capitalism itself was causing catastrophic global warming.

Biehl is the author of Ecology or Catastrophe The Life of Murray Bookchin, the editor of The Murray Bookchin Reader, and the author of The Politics of Social Ecology, a primer on Bookchin’s ideas. Today she joins to tell us a bit about Bookchin’s life and work.

Nathan J. Robinson

When you meet people who have not heard of Murray Bookchin or are unfamiliar with his thought and work, and if they ask you to tell them why you think his work is important or has enduring value, where do you begin?

Janet Biehl

I, firstly, have to situate him as a leftist and socialist revolutionary. He came out of the communist movement, but he innovated a post-Marxist set of ideas for the left that he began developing and arguing for in the 1950s, and continued for the rest of his life. And instead of structuring a radical movement around a supposedly revolutionary proletariat, which turned out not to be revolutionary, he thought that it was necessary for a socialist movement to organize around ideas of democracy and ecology.

He perceived early on that the limits of capitalism were ecological. He began to realize that in the 1950s, when there were investigations into the effects of chemicals and food on human health, and he thought that while maybe the proletariat didn’t rise up because they were immiserated, surely they would not stand for insults to their health from consuming chemicals in foods and would rise up. It didn’t quite work out that way, but it was a valid insight, and has only become more valid as the decades have gone on.

He thought that to prevent the powers that be from running the show—the political and economic elites—he thought that power needed to be returned to the hands of the people directly. Democracy needed to be a matter not of representation of people going into voting booths and sending representatives to Washington to make decisions on their behalf where they could easily become corrupted. He thought that power had to stay with the people in their localities. He argued for citizens’ assemblies, or what I like to call “assembly democracy”—he didn’t use that term, but it seems to me to describe it.

It’s a democracy organized around people in assemblies making decisions about their communities, and then over broader areas. The assemblies would send mandated delegates to confederations, where decisions could be made in the aggregate for larger areas. The purpose was to ensure that power flowed from the bottom up and not from the top down. He argued for this the entire rest of his life until his death in 2006. He started a school called the Institute for Social Ecology, and leapt indefatigably around the United States, Europe, and in other parts of the world, to try to build a movement around these ideas. But, I have to say, by 2006, he had not succeeded in building a strong movement that he dreamed of in the United States and died basically a disappointed man.

Robinson

I first encountered his writing when I was in college when I was about 19. I took a class called “Marxism versus Anarchism,” and I came across his essay “Listen, Marxist!” This class was about the disputes and historical differences between Marxist and Anarchist thinking. When I first came across his work, the first word I would probably use to describe it was “bracing.” He’s a unique figure as a leftist because he developed a set of leftist ideas that really are totally unique and his own, in that he synthesizes the best of each different strand and takes the best from various traditions. He asks: can you take the best of the environmental movement and infuse that with some of the important insights of Marx and the best of direct democracy in Athens? It’s this fantastic fusion of ideas that when you come across it is like nothing else you’ve encountered before.

Biehl

He took very seriously the maxim of Rosa Luxemburg, that our choice is either socialism or barbarism. After the Second World War, when many of the people who had been on the left just went galloping into the institutions of capitalism, Murray refused to do that, and said it’s not a matter of giving up on revolution. We have to rethink it because the proletariat might not be revolutionary, but capitalism is still barbarism, and we can’t accept that. And the question is, what are the mechanisms by which it will and must finally destroy itself? It is based on exploiting people, and it’s dehumanizing, so it can’t possibly thrive. So, how do we get people to realize this? There are so many ways people are taken in.

His goal, his North Star, was always to build an anti-capitalist movement. And yes, you’re right, he drew on all sorts of strands. He got the idea of assembly democracy from Ancient Greece and from the Vermont town meeting. Historically, the ancient Athenian polis was men only and built on slavery and the exclusion of anybody non-Athenian, and his idea was to extract the idea and nature of that institution—of citizens horizontally making decisions—from that historical context and say while that all serves to negate it, we can look at the institution itself that’s worth rescuing. For the Vermont town meeting, these people were making war on Indians all the time and were religious fanatics (they were Calvinists), but we can extract that institution of horizontal face-to-face democracy from that sordid historical context, and think about how we can make that type of institution relevant today, but obviously with participation expanded to everybody, and without making war on people of other colors, and so on.

Robinson

As I was reading your biography, you have a quote from him from his book called Ecology or Catastrophe, and feels so relevant at a time when we see immense heat waves across the United States and Britain. This incredible quote from him is from 1964:

“This blanket of carbon dioxide tends to raise the atmosphere’s temperature by intercepting heat waves, going from the Earth into outer space. Theoretically, after several centuries of fossil fuel combustion, the increased heat of the atmosphere could even melt the polar ice caps of the earth, lead to the inundation of the continents with seawater. This is symbolic of the long range catastrophic effects of our irrational civilization on the balance of nature.”

He was really one of the earliest people to warn, not only about the threat of the climate catastrophe, but tying that catastrophe to capitalism.

Biehl

Yes. I want to point out, firstly, the title Ecology or Catastrophe is the successor of socialism or barbarism. But, the idea of climate change was still pretty new. There were scientists investigating it at MIT in the 1950s, and people were beginning to write about it in specialized journals. But, his insight was that to solve this problem, we’re going to have to reconstruct the whole society. It’s not something that you can just adjust to, and his word for making minor adjustments to accommodate ecological problems was “environmentalism.” For him, the word “ecology” stood for that reconstructed society that was post-capitalist in which people would re-empower themselves and make decisions locally where town and country would be reintegrated. That was critical to his ideas.

He wrote a lot about cities and about how we have this hypertrophy of urban life, existing alongside the hyperindustrialized agriculture. His idea was the town and country needed to be reintegrated the way they had been in the past. And yet, he wasn’t a primitivist, and argued against that all the time. One of the legacies of his Marxist background is that he embraced and understood the importance of technology, especially in terms of eliminating toil, because that’s what would make it possible for people to attend all these meetings and govern themselves—they wouldn’t be having to work because machines would do the work. He was really excited about the advent of, for example, the miniaturization of computers, and of all different kinds of technologies that would lead to what would make this new society possible.

Robinson

Yes. It seems his work answers numerous questions, like: How can you take the insights of Marx without adopting the kind of rigid, dogmatic authoritarian Marxism of the 20th century? How can you adopt an ecological worldview without being a primitivist who romanticizes early societies and gives up the benefits of modern technology? How can you take the good in the Anarchist tradition without the individualism? In each case, trying to synthesize these insights and steer away from extremes towards this wholly new and dialectical, if you will, approach that weaves these strands together, as I’ve mentioned before.

Biehl

Yes, it was a constant sorting of the ideology. It wasn’t a matter of accepting or rejecting the ideology as it was. Ideology can be right about some things and wrong about other things, and the important thing is to identify what remains valid and useful for the future and discard the rest. That can lead to confusion for people who confuse the part with the whole.

Robinson

I also liked him because his ideas were constantly evolving and changing over time. Could you describe the way that he developed his ideas?

Biehl

He always tried to respond to the time in which he lived. I found that as I was working on his biography, it nicely tended to break down into decades. He realized that anti-statism was a big issue. The Marxists kept attacking him for that. He realized finally, after a point, that the people who he was most likely to persuade of the validity of the ideas were people who were already anti-statists, i.e., anarchists. So, by the time I met him, his passion was to try to show the international anarchist movement that Social Ecology, this idea about participatory face-to-face democracy was their natural politics and should adopt it. It was a way that anarchism could become relevant in society rather than, as is so often the case, either just a matter of archivists attending the writings of the anarchist past, or else just throwing rocks at police in the street—there had to be something in between.

For him, he thought it was quite obvious that they should accept this set of ideas about democracy and ecology. And so, when I knew him, he was basically barnstorming everywhere, talking mainly to anarchists at that point because, like I say, he thought that they would be most receptive. But it turns out that they didn’t like the idea of majority voting because it was majority rule. Majority rule—that’s still rule, isn’t it? So, that was when he concluded these are just individualists; they’re not going to go along with majority voting and just want things to be their way or no way. That’s when he decided that it really needed to be about a communal movement rather than an anarchist one.

Robinson

You mentioned there, when you knew him, you were his collaborator and partner for many years. Could you tell us what your first impressions were when you first met him?

Biehl

I was living in New York and saw him speak at the Socialist Scholars Conference and at some other conferences in New York. I was thrilled by what he was saying. I was in graduate school at the time at the Graduate Center at CUNY, and was trying to decide if I really was going to become a professor, and here he was talking about building a movement. He said this is a movement that needs theorists, writers, and talented people to persuade. And I thought, “Here’s my chance to do something relevant to building a better future,” rather than writing articles—I’m sorry, I had a very dim view of academics at the time—that six people are going to read in journals, including my mom.

Robinson

That’s why I’m not an academic.

Biehl

Also, at the time, academia was full of post-structuralism, and it rubbed me the wrong way. I decided I’d rather come up to Burlington and listen to Murray talk in his living room. At the time, he was writing two books: one was a history of revolutions and popular movements within European and American revolutions that was later published in four volumes as The Third Revolution, and then he was also writing a book about dialectical philosophy called The Politics of Cosmology.

He was really on a tear; he would write a chapter every week or two alternating with these two books, and give lectures on them in his living room. It was just mind-boggling to me. And at the same time, on Friday nights, we would have green meetings of our political group. Not that many major thinkers open their front door and say, “Come on in and be in a group with me. My vote carries no more weight than yours.” But that’s what he did.

We had a group of about 15 or 20 people. We ran political campaigns in Burlington, developed programs, and tried to be a model for this kind of politics that he was describing and trying to persuade the world to accept. And yes, it was remarkable. There were study groups all over Burlington with people studying subjects like the French Revolution and economics—we had a little informal university going here. And at the same time, he was engaged in debates with the deep ecologists with him who had a very dim view of humanity—Murray called them misanthropic—and getting into debates with anarchists who wanted to do nothing but throw rocks at the police.

It was very exciting. Vermont is a place that’s very small scale. I see Bernie Sanders and Patrick Leahy in the street from time to time. The government doesn’t seem like it’s a remote, distant place, and instead, it seems like it’s a place where you really have a chance to interact with and become part of a small scale political culture. So, the utopia that he talked about almost seemed possible here, like you could reach out and touch it.

Robinson

He was not a particular fan of Bernie Sanders, though, at the time. Is that right?

Biehl

We got into many arguments with Sanders, who we regarded as an unreconstructed worker oriented socialist, rather than someone who’s arguing on behalf of the citizen rather than the worker.

Robinson

The Murray Bookchin vision of what political life should be for people is profoundly democratic, very communal, and about participation. How do you summarize the kind of transformation that he talked about and advocated?

Biehl

He talked about returning so many things to the hands of the people, like economic power. He thought that the economy needed to be put in the hands of bottom up, self-governing bodies based on the assembly. He wanted technology to be decentralized—he would have loved Apple computers, maybe not the company, but the decentralization that the laptop computer brought about was just remarkable to him. He wanted automation to be small scale. It was about decentralizing and breaking up cities to small-scale cities that are integrated with agriculture.

So, the theme that I found when I was working on the biography was that so many of his ideas were about decentralizing different parts of society and reintegrating them into a new whole. I call it eco-decentralism in the book, but that’s not a term he used. It was decentralizing for the purpose of restoring control to people. When I looked at what happened with him and anarchism, I wondered, “Why was he attracted to this ideology that he later broke with?” When I read his actual reasons for embracing anarchism in his earlier writings, I noticed that it’s because the state makes people passive. He admired that active political engagement in the Athenian polis, where people could actively be involved in their society, rather than be passively turned into anonymous faceless crowds of the New York that he was living in.

Regardless of what you think about anarchism, that’s something that we need to preserve from him. He agreed with Aristotle that we are political animals and that we need to engage. That was, I think, one of his main goals: to create citizens who were engaged at the local level and in the surrounding regions and who didn’t just turn over their minds to the state.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth. Listen to the full interview on the Current Affairs podcast.