We Can’t Make Healthcare Fair Until We Reject the Logic of Scarcity

In his new book, physician writer Ricardo Nuila uses the safety-net hospital where he works as a model for healthcare reform. It’s true that healthcare ought to be public, universal, and government funded, but to build a truly just healthcare system and a healthy society, we must reject the underlying logic of scarcity built into the healthcare system and the idea that healthcare is simply a transaction or a fair deal.

Recently President Biden tweeted the following:

Look, I’m a capitalist. I have no problem with companies making reasonable profits. But not absurd levels on the backs of working families and seniors—it’s about basic fairness.

A subsequent tweet described how the administration is “taking on greed” by lowering drug costs, “cracking down on hidden, surprise junk fees,” and making corporations pay their “fair share” of taxes.

Fairness is commonly spoken about among people in power. In 2021, Biden gave remarks about bringing “fair competition back to the economy.” Elizabeth “capitalist to my bones” Warren in 2018 proposed reform so that we could have “fair markets, markets with rules.” Hillary Clinton said in 2015 that we needed to rein in capitalism “so that it doesn’t run amok.” In 2021, Nancy Pelosi said that billionaire wealth hoarding was “simply not fair” and that we needed the economy to give people a “fair shot this time.” Perhaps Donald Trump, a demagogue, capitalized best on average people’s sentiment that the economy is unfair when he said it was “rigged” against all of us. In 2020, Pew Research found that nearly 70 percent of American adults think the economy “unfairly favors the powerful.” In 2022, Pew found that a majority of Americans think that the economy helps the wealthy and hurts the poor and middle class.

Does anyone think our healthcare system is fair? It’s hard to see how that could be the case. Health insurance company profits have increased by nearly 300 percent in the last decade or so. Pharmacy benefit management companies (aka the “middlemen” standing between you and your medications) UnitedHealth Group, CVS/Aetna, and Cigna took in a combined revenue of nearly $1 trillion last year. Meanwhile, if you’re not lucky enough to have employer-sponsored health insurance, you’ll find that, nationally, average premiums on the ACA marketplace have never gone below $300 per month since 2018. The marketplace itself is a scam because there’s no way for you to rationally pick a product that is affordable or that will actually meet your needs (like covering vision, dental, or hearing in the policy). Around 30 million people are uninsured, and healthcare horror stories and medical GoFundMes abound. Congress has recently decided to reverse Trump-era increases to Medicaid (and food stamps), which will make life even more difficult (and dangerous) for the most vulnerable. As Bernie Sanders likes to remind us, we remain an outlier among industrialized nations in our refusal to guarantee healthcare to everyone.

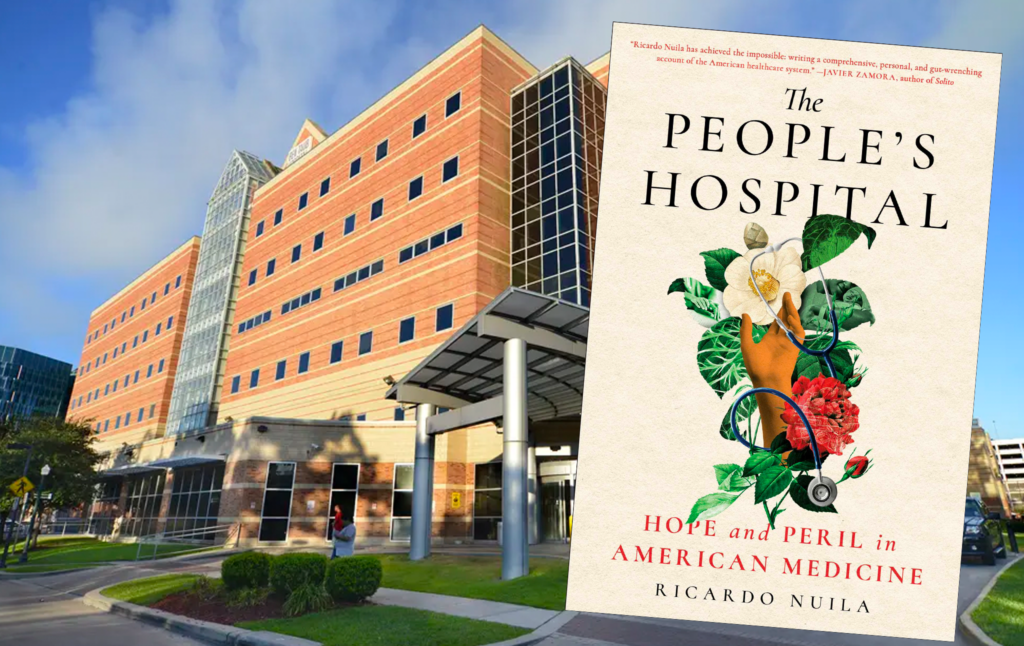

Perhaps it’s unsurprising, then, that fairness1 operates as a narrative thread throughout physician writer Ricardo Nuila’s new book, The People’s Hospital: Hope and Peril in American Medicine. Nuila is an accomplished writer of fiction and nonfiction (covering the emergency response to Hurricane Harvey, COVID, and maternal mortality in Texas), and the book has received much attention in the few weeks it has been out. The New Yorker featured an adaptation, the New York Times Book Review gave a brief review, the New York Times published a related op-ed by Nuila, and the book has been covered on podcasts and publications including NPR’s Fresh Air, The Guardian, Explore the Space, An Arm and a Leg (a podcast about healthcare costs), Houston Public Media, the Texas Standard, Texas Monthly, BookPage, and The Independent’s books of the month list. The reception has been largely one of praise (my favorite example: “This book is fuckin’ awesome”). Nuila is a beautiful writer, and he shows great compassion for his patients. But it’s worth taking a closer look at the underlying analysis2 of healthcare that he deploys—and the kinds of solutions he does (or doesn’t) recommend.

Nuila is a hospitalist—a doctor who takes care of adults who are admitted to the hospital. He has practiced for over a decade at Ben Taub General Hospital, in Houston, which is part of Harris County, one of the most diverse and populous counties in the country (and where I have lived since 2005). As Nuila explains, Ben Taub is part of Harris Health System, a mostly publicly funded (through property taxes, Medicare, and Medicaid) healthcare system that was created by a ballot referendum in 1965. Initially a “hospital district,” it has expanded to include community clinics. It accepts all patients regardless of ability to pay, including people who are undocumented (which makes a person ineligible for Medicaid or the ACA healthcare exchange). In this sense, it’s a “safety-net hospital”; it also operates on a means-tested eligibility system, a point to which we will return. I graduated from the same medical school as Nuila and trained in the same hospital system (although I became a general pediatrician) in the Texas Medical Center just a few years after he did. I never met Nuila, but I’d heard of him, and I’d read his writing over the years and enjoyed his fiction in particular.

Nuila has written what he calls a “love letter” to Ben Taub, but it is much more than that.3 What I am most concerned about is the book as what Nuila has called a “piece of rhetoric” about healthcare policy (as well as how we think about poor, working class, and marginalized communities’ access to healthcare). While Nuila has said that he “didn’t come into this book wanting to make a grand statement about healthcare—I wanted to write patients’ stories,” he does, nonetheless, make a number of arguments about healthcare and healthcare reform that are useful and some arguments against Medicare for All that I found unconvincing. Within those arguments, certain themes warrant closer scrutiny because they frame the terms of the debate strictly within the confines of the current system and thus limit our imagination of what’s possible.

I can relate to a lot of what Nuila writes. Ben Taub is not a place one could easily forget. The hospital had already begun physical changes in the waning years of my training, but I remember the open wards in the emergency department (I hadn’t known they were called Nightingale wards after Florence Nightingale, who, Nuila explains, studied and advocated for better spatial architecture of hospitals); the patients lined up on beds in two rows on either side of a walkway, some in plastic siloes (suspected tuberculosis or droplet precautions?) which doctors leaned into to listen with their stethoscopes; the “Team Hall” area where surgical patients were seen, in what one of my classmates called “glorified primary care” (in other words, the patients had shown up because of lack of primary care for problems that had festered and become more serious); the advanced cancer diagnoses that should have been detected much sooner; young patients dying; patients curled up in stiff waiting-room chairs, waiting hours and hours to be seen; patients in the throes of psychosis or other psychiatric emergencies who required sitters or “psych techs,” large tall men who were kind appearing but could spring into action to handle a combative patient if necessary. The Anywhere But Here cocktail (Ativan, Benadryl, Haldol) given to combative patients. The patients who came in in handcuffs and orange jumpsuits. (Harris Health is the healthcare provider for the Harris County Jail.)

After medical school, I spent part of my residency at Ben Taub on the pediatric inpatient wards, in the pediatric emergency department, and in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). I also did my required outpatient clinic training at Ben Taub—that is, until the pediatrics department in the hospital was shut down in 2010 in order to enable “the most efficient use of our resources,” according to the CEO at the time. (Harris Health moved my training clinic to an offsite location.) I worked my very last shift of residency in 2012 at Ben Taub—the overnight shift in the emergency department (at that point, we saw pediatric patients under the supervision of adult emergency medicine physicians). I left before the sun came up, when the hallways were quiet before the bustle of the 7 a.m. shift change.

When Nuila tells stories about the patients Harris Health treats—the poor and working class, the undocumented and uninsured, racial and ethnic minorities from different corners of the world—I can relate. I worked in a private safety-net clinic in Houston as a general pediatrician for six years (I’m on hiatus from clinical work). Most of my patients had Medicaid and were Latino or Black; some were uninsured; many came from immigrant families. Similar demographic to Harris Health. Although our clinic took care of anyone regardless of coverage, we sometimes referred patients to Harris Health—“la tarjeta dorada” or the Gold Card, referring to the eligibility system—because our clinic or hospital system didn’t cover some service they needed. When Nuila describes his time working at Harris Health’s People’s Clinic seeing a couple dozen patients a day and putting out fires—managing very out of control chronic conditions like diabetes or high blood pressure—I can imagine what that’s like. Working as a pediatrician in an underserved clinic is similar, but for different reasons—most patients are too young to have out of control diabetes or high blood pressure, but they do have uncontrolled asthma, and increasingly they are overweight, are prediabetic, don’t have enough food to eat, are facing serious mental health issues, have complex care needs resulting from complications after birth, or their parents cannot afford to pay for their medicines or other necessary healthcare.

Many of us who have worked in safety-net systems may believe in some notion of social justice or service to those marginalized by society. But the thing about training in the Harris Health system and working in a safety-net clinic is that neither quite struck me as fair if I see fairness as a consideration of the total apportionment of resources available to all people. In other words, the social determinants of health—such as good and affordable housing and public schools, nutritious food, clean water, good-paying jobs—had been distributed either unfairly or not at all to my patients and their families, many of whom lived in polluted neighborhoods near petrochemical refineries (Houston is sometimes called the “Petro-Metro” in this regard). Mostly, as years went by, I felt increasingly ashamed (and angry) at the way in which the pace of clinic work left patients feeling neglected (they always noted on surveys how we never spent enough time with them) and doctors feeling depleted.4

My feelings about safety-net systems are probably closer to what Rachel Pearson, a pediatrician and writer who covered the book for Texas Monthly, wrote. She rightly points out that working on the “righteous side of an often-dehumanizing health system” could lead someone to make “too sunny an assessment”5 of their work. And, most importantly, she pointed out that a healthcare system that generally remains “profoundly segregated by race and class” is, essentially, “separate but equal” and “should be regarded as unacceptable.”

Fairness is good, but what about justice?

Fairness comes up repeatedly in the book as Nuila assesses the care his patients have gotten—and the cost they incur for that care. While fairness is a good standard to have in society, it is insufficient to consider fairness only within the confines of the Harris healthcare system. Healthcare needs to be conceived of—and implemented as—a vital public good that is more than just a commodity or a question of whether someone got a fair deal on the market for a service rendered by a physician/healthcare organization.

First, “We have it right down to the dollar,” Nuila notes in reference to “complex tables and eligibility charts to determine precise levels of fairness, which is how we come up with numbers … to help us assign health coverage. We use the numbers to determine how best to deploy limited resources.” What he’s describing about eligibility for public healthcare seems like a good thing. Who can argue with fairness? If fairness is based upon means testing or dollar metrics, this allows us to feel impartial about doling out care.

In this scenario, fairness situates our moral assessment within a scarcity, or austerity, framework, which is not a good benchmark for what ought to be considered acceptable—or aspirational. As explained by Beatrice Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant in their recent book, Health Communism, the debate around universal healthcare in the U.S. is often framed around “a principle that rationalizes political notions that not all people are in fact equal in deserving assistance or support.” (Nuila notes this as well, writing that “healthcare remains linked to the question of worthiness.”) So, if you happen to labor for an employer that offers health insurance, good for you. If not, you’re out of luck. You could just pay cash for your healthcare, but what if you don’t have that kind of money? You could try your hand at a public program. But public programs are set up specifically to distinguish between those deserving of care and all the “fakers, cheats, imposters, and malingerers” out there just waiting to steal our tax money. Thus, Adler-Bolton and Vierkant continue, we have “modern practices like means testing or disenrolling beneficiaries as part of a never-ending war against ‘waste, fraud, and abuse.’” One effectively becomes a burden to society and subject to the whims of legislators who can threaten to cut your benefits at any time (as many as 15 million people may lose their Medicaid in the recent cuts).

Just like government programs such as Medicaid and disability (SSI and SSDI),6 Harris Health has limited resources and so must determine who is the most deserving of these resources. At Harris Health, Nuila’s patients submit to extensive means testing to determine what level of financial assistance they will receive. Everyone is let in the door at Harris Health. And they won’t ask you financial questions (until you are stabilized medically). But this is a system of austerity, not abundance. Fairness, in this system, justifies what I would call incrementally-less harm than the outright exclusion experienced at other healthcare facilities. The outcomes achieved in this system may technically be “fair” according to allocation of scarce resources, but those resources are only made scarce because of political decisions,7 and these outcomes do not necessarily approximate justice, or the fair apportionment of resources in all aspects of a person’s life.

Consider some examples of Nuila’s patients. Roxana is undocumented and has no health insurance. After a surgery at another hospital to remove a tumor (which was performed because it was “urgent”), she experienced a severe complication that left her with “charred wood” for limbs. The hospital sent her home to “auto-amputate” and, essentially, to die (she was dependent upon friends from her church and her daughter, who flew in from El Salvador, to care for her). Reading about Roxana made me livid. What kind of society sends home a woman with dead limbs to auto-amputate?

Roxana eventually shows up at Ben Taub with the hope of getting amputations of her dead limbs. Because of her condition, Roxana qualifies for the highest level of assistance at Harris Health. Still, she’s subjected to a co-payment schedule. She is to pay $3 for clinic visits. $3? This strikes me as incredibly petty and even cruel. What’s more, there’s a disclaimer to her eligibility plan: if she can’t pay the co-pay, services will still be provided. Then why demand the co-pay at all? Because resources are limited.

Roxana initially gets admitted to the hospital for antibiotics to treat infected tissue in her limbs. Less than two months later, she gets her amputations. Nuila briefly discusses how there are waiting lists for non-emergent surgeries in Harris Health and how he could have tried to expedite Roxana’s surgery. But he decided that the surgeons had made “fair decisions” about the timing of her surgery.

But it turns out that Roxana’s cancer has spread to her brain. This will limit her chances of survival. “The Gold Card didn’t cover prostheses for patients with metastatic cancer,” Nuila writes.8 “Prostheses are expensive, and in a safety-net system, expensive items have to be doled out judiciously, out of fairness.” So Roxana would have to pay $30,000 for each prosthetic limb. What comes next? A GoFundMe.

Roxana ends up getting leg prostheses thanks to the help of her church community and a local charity. Nuila meets up with her at a rehabilitation therapy session, which is the closing scene of the book. It’s a heartwarming scene, and you can really feel the bond that Nuila has with Roxana, how she inspires him because of her resilience and how she trusts him. It’s good. But then my heart sinks reading the last line of the book: “[I] see … the people of a city getting the best out of one of their own. It’s every penny from our pockets well spent.” I find myself disappointed that cost efficiency gets the last word (literally and figuratively) in what is otherwise a great ending scene.

In the case of Stephen, who was an uninsured homeowner with assets, the payment plan was 100 percent self-pay. (He had lost his health insurance when he lost his job during the pandemic.) His hospitalization for care of tonsillar cancer ended up being over $32,000. We’re told Stephen is conservative, though, and that he believes in capitalism and limited government. Stephen points out that $32,000 is less than the price of a new truck. “It would be difficult, but he could pay it,” Nuila notes. And Nuila finds himself thinking, at least this man won’t be fleeced. “Through it all, at least the safety-net system made him feel worthy of the treatment it offered.” Here, again, I’m angry. Why should Stephen have to pay such a massive amount? Likely, his cancer is not going to be a one-time thing. What about the next treatments and everything after, or any other healthcare he might need? Cash pay doesn’t seem sustainable.

Geronimo, who “worked despite having epilepsy” and “was trying not to be a burden” to society, has chronic liver disease and needs a liver transplant (for which he will have to be transferred to another center, as Harris Health does not have a transplant program). Geronimo could qualify for Medicaid, which would fund the surgery, but he doesn’t qualify because his SSI income turns out to be $179 in excess of what was allowed for Medicaid eligibility. The team turns to heroics. In one particularly notable scene, the director of Texas Medicaid asks for Geronimo’s recent bank statement to be faxed over so they can “expedite” his approval. Like all patients needing a liver transplant, Geronimo is critically ill. And they want his bank statement! This is the height of dystopian. Nuila admits that he tried to put on a strong face for the medical team, but “the team could see my faith was shaken. ‘I’m worried about the numbers [on the bank statement],’ I said. … ‘I’m worried none of this will make a difference.’”

What happens next is horrible. When your liver doesn’t work, your blood can’t clot properly, and Geronimo ends up dying from a brain bleed just days after he’s approved for transplant after a Hail-Mary effort involving a local Congressman and Texas Medicaid. Nuila says that it’s very likely that Geronimo would have lived if his Medicaid hadn’t been cut over $179. He says that the man’s death was “a tragedy” and that he would have to “continue to do my job tomorrow as if this never happened.” But, he concludes: “Money didn’t stop us from trying what we could to help. He was at a public hospital, yes, but he got the same care he would have received at a private hospital.”

Nuila admits that conditions in Texas are bad. At one point, he’s calling around transplant centers in other states, and one social worker in Missouri tells him, “Texas sounds tough.” Talk about an understatement. Immediately, in the next paragraph, Nuila gets into how he

respected my home state for many reasons, including the economic opportunities it’s capable of creating. I paid $6,500 per year in tuition—the lowest in the country—for a private medical school education, in large part because of the state’s subsidies. Beyond this, there seemed to be jobs available for everyone in Texas. Some of my patients at Ben Taub were homeowners. They had come from nothing in East Texas or El Salvador to purchase a house in Houston. It meant something to give people the ability to do this, and you had to give some credit to legislators for keeping the Texas economic engine moving. Would the cost of caring for the state’s most vulnerable and sick impede the economy? Legislators seemed to think so. I wasn’t convinced.

Really? What does any of this have to do with the horrifics of Geronimo’s situation? These factors mitigate the fact that a cruel means test made it so that $179 stood in the way of a patient and a lifesaving transplant? Why would the legislators’ fiscal conservatism be the idea to disprove and not “every patient deserves to be given the care they need”? There’s no need to defend a state legislature for setting up dystopian healthcare conditions—unless you are looking to give a fair or balanced depiction of things.

In these patient stories, fairness is not just a way to assess who gets what care and at how much cost. Fairness becomes a kind of justification (or even, perhaps, a coping mechanism for those working within the system) for why there are so few resources for people to begin with. This is the part of fairness that I can’t get behind. It precludes justice.

A Mildly Pro-Government Stance

Nuila makes the important argument that the government can fund and administer healthcare and do it well, counter to the all-too-prevalent anti-government taboo that pervades U.S. culture and politics (for a definitive debunking of conservative myths like “Socialized Medicine Will Kill Your Grandma” and “Government is the Problem, Not the Solution,” please see Nathan J. Robinson’s latest book). He mentions Harris Health and the VA as examples, noting the achievements of each system.9 These are very important arguments to make, particularly during a pandemic and considering that increasing numbers of Americans across the political spectrum support a single-payer government health insurance system. Medicare for All is popular, and the case for it is solid on moral as well as economic grounds. But Nuila’s mildly pro-government arguments are undercut ultimately by his doubt around the viability of Medicare for All as well the market-centric idea of “competition” that he has endorsed. For example, in a recent interview with the Texas Standard, he said:

I think that a public health care system could give basic health care to everybody, and that a private system could still exist and possibly even compete with the public health care system for patients. Imagine somebody who’s 22-years-old and is a worker and in our system right now has to purchase health insurance. But maybe if the basic level of health care was available, then the private side would have to compete for that person’s business and perhaps lower costs in order to do so.

In this sense, healthcare is a commodity, with businesses competing for our purchase of health insurance. But competition is not healthcare; it’s a term used by enthusiasts of the so-called free market. Recall that the ACA was supposed to make health insurance policies better by introducing competition into the mix. But this ‘competition’ has not amounted to wins for ‘consumers’ of healthcare. As explained in 2017 in The Intercept, “ACA exchanges were built on the fundamental idea that competition between regulated private insurance companies would improve quality and hold down prices. …” But this hasn’t been the case; millions of people still suffer what NPR has called “‘catastrophic’ health care costs.” And even though more people may be insured than before the ACA, more people are also underinsured because the ACA plans’ costs are simply unaffordable. And in the case of putting public and private plans side by side, we see how that has worked out in the case of Medicare Advantage—rightly called Medicare DisAdvantage because these plans “cherry pick” healthy patients, “lemon drop” sick ones, operate on a much higher overhead than traditional Medicare (15 percent versus about 2 percent), deny care more, and rake in high profits all while facilitating the encroaching privatization of Medicare. Why would we still think that private-public competition is a good thing?

Interestingly, Nuila has also admitted that we could just do away with insurance entirely. From the same interview:

Yes, that’s what I think is what Ben Taub can give to the health care debate, is that this is a model of health care that’s publicly funded and what that means is that it’s directly distributed to people at the county level, which means that instead of going through an intermediary – a middleman like insurance – the health care is delivered directly to patients who need it.

Ultimately, what Nuila proposes is most clear in his New York Times op-ed: a national referendum on health care. “Americans should vote yea or nay on a system that provides basic health care for all.” Then, he contends, we could design our system. He proposes a system which would be similar to the public system at Ben Taub, which operates without the profit motive. Essentially, he seems to be asking for a nonprofit socialized system which leaves no one out. So why not Medicare for All?

To go through, in detail, all the injustices faced by Nuila’s patients would take another book in and of itself. The fact is that in our current healthcare system, the estimated 70 million people (nearly 30 million uninsured, 40 million estimated underinsured before the pandemic) who are not deemed worthy enough of healthcare are experiencing these things every day. If a patient comes to a safety-net system, and they are given care, it is definitely a good thing. But we also need to ask why patients have been shuffled into this safety-net system in the first place. Adler-Bolton and Vierkant have used the term “surplus” to describe people who, in our economic system, are considered less-than and a burden to society.

Surplus is not meant as a strict definition. Essentially anyone can come to be considered surplus,10 which is to say, anyone can come to be considered a “burden” to society by becoming unable to work; by losing a job or changing jobs; by lacking money to pay for healthcare; by belonging to whichever groups society has decided to marginalize along lines of ability, race, gender, nationality, or other characteristic; or by being imprisoned or otherwise targeted by the state for surveillance. (When we think of the millions impacted by Long Covid, for instance, some of whom may be unable to work, we can see how truly vulnerable we all are to becoming surplus.) Because healthcare is not functionally a human right in the U.S., to quote Adler-Bolton and Vierkant again,

Health under capitalism is an impossibility. Under capitalism, to attain health you must work, you must be productive and normative, and only then are you entitled to the health you can buy.

Nuila admits the same, essentially:

To receive good medical care that is streamlined and straightforward, multiple factors must come together. Depending on how someone receives insurance, a patient has to make sure their job remains steady, or has to stay married, or has to make sure they earn enough for co-pays and treatment. Any disruption of this delicate order can result in the illness’s running rampant. To make things worse, this tightrope walk often happens at a time of great bodily upheaval, when the person is at their most vulnerable.

Since there is truly no conceivable reason why any person doesn’t deserve to have all their healthcare needs met, and we live in a wealthy nation, we must radically transform our conception of healthcare and health into something that will allow all people to flourish. If we limit our thinking to the confines of how the surplus is treated—means tests, limited resources, draconian budget cuts—then we can only imagine a system based on similar austerity. But just as we cannot make a capitalist economic system built on exploitation truly fair, we cannot make a healthcare system built on scarcity truly just. What we need is, as Adler-Bolton and Vierkant argue, all care for all people. They ask: “[W]hat are the social and material needs of all? How can we allocate resources and activity in order to meet those needs? … ” In this vision of healthcare and societal well-being, health is not just a state of being that comes about in a doctor-patient relationship. Health comes about by the creation of a healthy society and healthcare for all.

We know that a universal Medicare for All system would cost less than our for-profit system and that most Americans would pay less in taxes for M4A than they do now in premiums, deductibles, co-pays, co-insurance, prescription drug bills, surprise bills, and so forth. Here’s what Nuila says about Medicare for All:

Medicare for All proposes such a system: one standard of care, one method of healthcare, one insurer—the US government—for everyone. I’m not sure the majority of Americans would accept such a system, especially because of what they would relinquish. Private health insurance allows a person to experience healthcare in private. It also allows people to make more choices in their healthcare and to receive certain types of healthcare—particularly specialty care—faster. We shouldn’t take these benefits lightly. Any time I walk into a room shared by four patients and hear the heaves of somebody vomiting or even the smell of excrement, I can feel how preferable it is to have a private room. The question is whether the privacy is worth what we’re paying for it. We’re not only paying a premium financially, we are also sacrificing fairness, equality, and, in many cases, quality of care.

He’s not sure the majority of Americans would accept it: While there is much mistrust of the healthcare industry to overcome, Nuila’s patient Stephen seemed a good test case of this theory. Stephen was described as a Republican who believed in limited government and was skeptical of Ben Taub as a public facility. However, he was won over by the friendliness of the staff, good medical care, and Nuila’s honesty about giving him a fair deal. At one point, Nuila notes: “He didn’t like the idea that the government was providing his healthcare, but at the moment, he would take what he could get.” I imagine many people would also “take” the free (at the point of service) healthcare compared to the nightmare system we have now. They would also certainly prefer a hospital bill of $0 over a $32,000 one.

The other concerns about delays in care and private rooms seem overblown and hypothetical, but they do warrant comment. It is true that while the government can pay for such a universal program, the bigger issue is creating the resources11 to operate Medicare for All. This means appropriately scaling up labor (everyone from pharmacy technicians and physical therapists and community health workers, to doctors and nurses) and buildings and equipment and programs so that we can truly give everyone the care that they need without undue delays in care.12

In a publicly financed system, we aren’t subject to the constraints of the for-profit market. We saw how badly the market handled, for example, the supply of ventilators during the initial phase of the pandemic. The market also has kept lifesaving vaccines from people in the global south due to intellectual property law. But we can design the public system we want. We start from what people’s needs are and build from there. We can build facilities with plenty of private hospital rooms (we can even make those rooms beautiful and inviting, not ugly and harsh, so that hospitals feel more like places of healing than like warehouses). We can make sure that we adjust our production of medical professionals and equipment so that we don’t have undue delays in care. Just because, in the current system, private health insurance allows a person to see a specialist faster than they would with public insurance, that doesn’t mean that the same disparity will exist in a future system. We shouldn’t aim to recreate the same injustices today in the system of tomorrow—or use those disparities as reasons not to try for something better than what we now have.

As for Nuila’s point about moral hazard, the idea that once consumers have access to healthcare, they will use it, perhaps excessively: I don’t think this is a very convincing argument against a single-payer system given the horrors incurred by people in the current for-profit system, even if people do tend to use something that’s given to them. With proper health education and community health interventions built into our healthcare system, we can manage people’s needs alongside measures to build the increased capacity we will surely need to take care of everyone. As Kelton points out, the U.S. has plenty of labor and resources at our disposal.

Medicare for All is an important reform in the financing of healthcare. It is not socialized medicine; it is socialized payment. But we do need both socialized healthcare payment and socialized medicine and to remove the profit motive from healthcare so that we can give everyone the care that they need. We need to prioritize the social determinants of health, or what Adler-Bolton and Vierkant call the “social-infrastructural aspects of life,” such that everyone has clean air and water, nutritious food, safe housing, good-paying jobs and education, and opportunities for leisure and the arts.

I understand, from personal experience, that there is honor and meaning in the work done by people in our safety-net healthcare system. And telling people’s stories helps keep us human in a very cruel system which often offers healthcare that is indifferent, bad, or uncaring. But, as writer and activist Yasmin Nair often argues, we need more than stories; we need fundamental change.

At one point, Nuila talks about Jundi-Shapur, “a great medical university with faculty and student doctors from all over Eurasia” which existed around 550 A.D. in Persia. At the teaching hospital there, he writes, “the rumor driving people across half a continent was even more revolutionary [than the care offered]: any person, female or male, from any race, of any class, could go there to receive care.” “This is the dream” for healthcare, he says.

Reading scenes like these—images of a truly universal hospital available to all, and stories of Nuila’s vulnerability alongside patients—makes me think that Nuila seems to have tapped into a kind of magic in medical storytelling. I must confess, though, that I’ve always thought the magic in medicine—indeed, medical training—lay in its potential to radicalize us, to get us to ask why we were seeing some patients in fancy private hospitals and others in more bare-bones public ones, why there were different tiers of care, and why resources were so scarce for some people but not for others.

We need radical change and a healthcare system in which for-profit health insurance is rendered irrelevant. Healthcare must be more than a commodity, something we aim to get a fair deal on. Our priority should be to build a healthy and sustainable society, prevent disease as much as possible (and treat it effectively when it arises), and give everyone the care they need when they need it, free at the point of use. This will require nothing short of a political movement as well as the willingness to challenge the market logic that is pervasive in healthcare.

The related narrative theme of ‘balance’ takes other forms in the book. There’s the lack of balance at the level of the human body in patients who are sick—liver test numbers being off, CD4 immune cells being out of balance in a patient with AIDS. There’s a lack of balance in life, as one patient is said to have “messed up the math” in their life. Then there’s balance as applied to the healthcare system: Ben Taub hospital was a “sweet spot” where science, people, and costs could be balanced (or “overlapped” in his Venn diagram mental interpretation of it). A good doctor, he wrote, “figured out the right balance between science and costs.” But this, to me, is more a descriptive statement of what doctoring has become in a modern for-profit system where pharmaceutical and other companies profit when doctors prescribe or use their products or services as therapeutics and in which physician ‘productivity’ (essentially, doing things to patients) in the workplace yields financial rewards. It’s not, to my mind, actually describing something that’s good or even desirable. ↩

Cost and waste are mentioned often as well. The issue here is that problems with rising cost and wasteful/excessive healthcare are symptoms of the underlying problem of for-profit healthcare, not the underlying causes. In another example, when asked on a podcast who he would identify as the “villain” in his book, Nuila identified nonprofit hospitals. With recent reporting revealing the despicable billing and treatment practices of some of these institutions, they certainly are villains. But again, these behaviors are symptoms of the underlying profit motive. ↩

Nuila has resisted categorizing the book as a memoir, but it does read like memoir in parts. It’s partly a family history of a medical dynasty: Nuila’s father is an obstetrician/gynecologist, and as he was growing up, Nuila saw the challenges his father faced as healthcare finance changed and it became harder and harder to see uninsured patients. (The two have also sparred over healthcare politics, his father being the more conservative of the two, we’re told.) His grandfather was also a doctor. The book also gets into Nuila’s personal thoughts on medicine and how he found the business aspect of medicine unappealing. He delayed his medical school matriculation for two years to work abroad—and then again after completing training— to try to find some other way to be involved in medicine. Ultimately, he came back to work at Ben Taub. The book is many other things: it’s part chronicle of patients’ lives and medical encounters. The book is part Nuila situating himself in the great tradition of literary physician writers, particularly those such as Anton Chekhov, who also wrote about injustice in medical care (lack of tuberculosis treatment at a penal colony). The book is part consideration of the “algorithmania” of American medicine and part history of U.S. hospitals and the corporatization of medicine, the latter which he calls “MedicineInc.” It is also a history of the origins of Harris Health. Dutch playwright Jan de Hartog wrote a scathing expose of Ben Taub’s predecessor hospital, Jefferson Davis Hospital, and the filthy and racist conditions there; a county judge went undercover as an orderly to confirm the reportage; and on the second try, a ballot referendum to create the hospital district was passed. ↩

One thing I remember and that I believe isn’t talked about enough is how the time factor of medicine—dictated by the bottom line—pits staff, patients, and doctors against each other. If you’re not careful, you can find yourself very resentful of everyone around you because of the constraints the system places on you. I think this can be more of an issue in primary care than hospital medicine; in the hospital you get down time throughout the day, and if you’re at a teaching facility, medical students and residents can do a large part of the work for you, the supervisor. ↩

Harris Health has had its share of problems in recent years. In 2015, Ben Taub could have lost its Level 1 Trauma accreditation due to a lapse in requirements. In 2019, the hospital received government scrutiny after untimely patient deaths. Harris Health is also the healthcare provider for Harris County Jail, which has received attention for alarming rates of inmate deaths in part due to lack of basic healthcare and in violation of safety standards as the county continues to fill its jail to strained capacity. NPR recently reported that the FBI is now investigating some of these deaths. Harris Health is noted to have had difficulty filling staffing positions. ↩

Sociologist Matthew Desmond, in his new book, Poverty, By America, has documented how the government has over time made it harder to get disability benefits. Most SSI and SSDI applications are rejected, he explains, and “in poor communities it is common knowledge that you must apply multiple times for disability … and you’ll need to hire an attorney.” He furthers: “[E]ach year, over a billion dollars of Social Security funds are spent not on getting people disability but on getting people lawyers so that they can get disability.” Lawyers take a cut of their clients’ money. ↩

Due to the political machinations of Republicans on the Commissioner Court, the Harris County tax rate was capped, and this has had obvious 2023 budget ramifications for Harris Health, whose leaders warned last fall that 10,000 patients could lose services if the budget did not allow increased funding to account for inflation. ↩

As Adler-Bolton and Vierkant note, there is a “cost-benefit analysis to determine whether disabled individuals were [are] worth therapeutic investment.” ↩

Nuila cites the following in regard to Harris Health: In 2015, Ben Taub was ranked best in the nation for care of acute coronary events (heart attacks). A 2019 RAND corporation study found that Harris Health system was the second-cheapest hospital in terms of not overcharging patients. ↩

As Adler-Bolton and Vierkant explain, surplus people are marked for extraction. They quote disability scholar Liat Ben-Moshe: “Surplus populations are spun into gold. Disability is commodified through [a] matrix of incarceration (prisons, hospitals, nursing homes).” I would also submit that low-income communities served by teaching hospitals experience a kind of extraction, even if the relationship seems mutually beneficial. Nuila notes that Ben Taub is a gold mine of pathology, as you see diseases there that you might not see elsewhere and how many doctors on their way to illustrious careers at big-name institutions “make a pit stop here.” While it’s instructive for doctors to learn about diseases they might not otherwise see (certain forms of tuberculosis, for example), the goal here ought to be to prevent those diseases in the first place (which means attending to the social determinants of health, as tuberculosis, for instance, is understood as a disease of poverty). ↩

As economist Stephanie Kelton has written, Medicare for All is not primarily a problem of cost. Kelton is an adherent of MMT, or Modern Monetary Theory. According to MMT, the federal government is the issuer of national currency and can thus create funds when it needs to. For more on this and how Medicare for All would be deflationary, see this discussion on the Bad Faith podcast. Of note, one doesn’t have to subscribe to MMT to understand that Medicare for All funding is entirely within our capacity. ↩

Readers may be tempted to look to Britain’s struggling National Health Service as an example of how our own single-payer system could go wrong. But the NHS has been defunded and privatized over the years by administrations that have been unable to entirely scrap the program, and the deficiencies of improper funding and management of the NHS are examples of how not to run a healthcare system. They’re not inevitabilities. Government surveys reveal that people like that healthcare is free at the point of use but dislike that the government does not adequately fund the NHS. ↩