Elvis Like You’ve Never Seen Him Before

How Baz Luhrmann’s “Elvis” took one of the most familiar stories in music history and somehow made it fresh again.

Elvis Presley is one of the most famous people who has ever lived. The iconography of his career is deeply embedded in both American and world culture, whether as tribute, such as One Direction recreating “Jailhouse Rock” in the music video for “Kiss You,” or as critique, such as The Clash borrowing the design of Elvis’ debut album for the “London Calling” artwork, with Paul Simonon smashing his bass in place of Elvis holding his guitar. Even if you’ve never sat down and listened to an Elvis record, you probably know tons of Elvis songs by osmosis. You can recognize his silhouette. There are a non-trivial number of people who work full-time as Elvis impersonators even today, nearly 50 years after his death. He’s a cultural icon, but, now more than ever, either a joke or a villain of history: a joke when he’s remembered as overweight and barely articulate in a Vegas hotel; a villain because, more than any other individual person, Elvis is synonymous with the long, painful history of white artists taking credit for Black music. “Elvis was a hero to most, but he / Never meant shit to me, you see, straight out / Racist—that sucker was simple and plain,” Chuck D rapped on Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power,” to which Flavor Flav adds, “Motherfuck him and John Wayne!”

But Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis—the best film of 2022—takes a story you think you know, a story of someone so famous you never needed to have it told to you, and turns it on its head.

Musical biopics have been somewhat en vogue ever since the Freddie Mercury biopic Bohemian Rhapsody grossed nearly $1 billion in 2018, with mixed results. Bohemian Rhapsody took the formula perfected in the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line (2005)—and definitively pilloried in Walk Hard (2007)—and gave it a staid, rote execution, with some awful editing for flavor. A year later, the Elton John biopic Rocketman breathed new life into the Walk the Line formula through the filmmakers’ genius masterstroke of creating a proper bursting-into-song musical while using John’s back catalog like a jukebox. Elvis emerges from this trend in popular film, yet stands apart from it. If you can draw a straight line without stopping from Ray (2004) or Walk the Line to Bohemian Rhapsody—and believe me, you can—there are a hundred lines, all of them crooked, from all across culture spinning towards Elvis.

Elvis is Faust: the German legend of a man who makes a deal with the devil, trading his soul for unbounded knowledge and pleasure on Earth. The man, in this case, is Elvis Presley, who Austin Butler, previously best known for his small role as a member of the Manson family in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, plays with just the right mix of charisma and vulnerability. Butler is so good that there are moments where you’re not sure if you’re looking at him or at archive footage of the man himself.

Elvis was raised primarily by his mother while his father was in prison. They were poor, the only white family in a Black neighborhood in one of the poorest parts of Mississippi. Though we see Elvis’ childhood only briefly, it shapes the rest of the movie: it’s where he first fell in love with Black music, evoked in a scene where kid-Elvis and his neighborhood friends run between a blues performance and a gospel revival ministry, the two sounds blending together and thrumming through Elvis’ body. “He’s with the Spirit,” a minister says. But the environment that birthed him is also the place he longs to escape, both for his own good and for that of his saintly mother. He reads Captain Marvel Jr. comic books and dreams of one day buying her a pink Cadillac. And so he’s willing to make a deal with the devil: Colonel Tom Parker.

Elvis is Amadeus, the story of Mozart as told by Antonio Salieri, a less talented but more successful composer played by F. Murray Abraham in the 1984 film. Elvis is narrated by Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks), who isn’t a Colonel, isn’t a Tom, and isn’t even a Parker. He speaks in an accent that’s two parts Goldfinger, one part West Virginia, but insists he’s a natural-born American citizen. Tom Hanks so rarely plays villains that his reputation is more or less exclusively one of unblemished wholesomeness. In 2020, he said that he was taking the role of Colonel Parker in part to “silence all your stupid questions about why I will never play a bad guy.” And silence them he does: Hanks’ Parker oozes malevolence. He’s always calculating how he can manipulate a situation so that he comes out on top. In the film’s framing device, he’s dying in 1997, dressed in a hospital gown, wandering through a casino. Where Salieri spends Amadeus confessing to destroying Mozart’s life and career and eventually killing him, the Colonel spends Elvis presenting his own defense. In this case, that means unwittingly confessing to destroying Elvis’ life and career and eventually killing him. Even though this is Parker’s story, we can see beyond him, see through his lies and into the sweet, soft boy he made a fortune exploiting.

“I am the man who gave the world Elvis Presley. Without me, there would be no Elvis Presley,” he tells us. “And yet, there are some who’d make me out to be the villain of this here story.” The Colonel first hears Elvis singing “That’s All Right, Mama,” already a hit locally, and upon learning that Elvis is white, he sees dollar signs. When he sees him perform on the Louisiana Hayride show, he’s sure. He becomes Elvis’ manager, taking him on tour across the country. Salieri is the only character in Amadeus who hears and envies the genius in Mozart’s music, in contrast to those in the royal court who nonsensically complain there are “too many notes.” But the Colonel recognizes Elvis’ genius only in how others react: how teenage girls, full of feelings they aren’t sure they should enjoy, scream when he wiggles his hips. In a film that has music in every pore, that carries itself like one big two-and-a-half-hour pop song montage, the Colonel is deaf to the music. He wonders why Elvis liked to hang out on Beale Street in Memphis. He never figures it out, but the answer saturates the air, as obvious as breathing: the blues.

Elvis is #FreeBritney: a phenomenally popular singer is trapped in a byzantine vice, under the clandestine control of a man supposedly taking care of them when they’re unable to do it themselves. After her breakdown in 2008, Britney Spears was put in a conservatorship administered by her father. When Spears spoke about it publicly at a hearing to end the conservatorship in 2021, she said she was abused and traumatized: medicated against her will, prevented from marrying or having more children, and forced to perform shows under threat of lawsuit or lifestyle restrictions. “It makes no sense whatsoever for the State of California to sit back and … watch me … make a living for so many people, and pay so many people, trucks and buses [on tour] on the road with me and be told, I’m not good enough,” she told the judge. “But I’m great at what I do, and I allow these people to control what I do, ma’am, and it’s enough. It makes no sense at all.” It’s a story not dissimilar to that of Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, whose entire life and career were controlled by abusive psychiatrist Eugene Landy for years following Wilson’s mental breakdown.

Elvis positions Elvis’ relationship to the Colonel in the same tradition. Elvis and Britney even both end up playing Vegas for years on end. In his deal with the devil, Elvis yields more and more power to the Colonel, with varying degrees of intentionality, until he has no means of escape—other than getting high on the drugs proffered by the Colonel’s quack doctor. Elvis always wanted to tour abroad, but the Colonel prevents it at all costs. (He insists it’s not safe, but it’s really because Parker is an undocumented immigrant to the U.S., and Elvis going on tour without him is a nonstarter.) At one point, Elvis attempts to assert himself, to leave the Colonel and go out on his own, and the Colonel presents him with an itemized bill for everything he has ever spent on Elvis. If Elvis paid it all back, he’d be broke. Meanwhile, Parker somehow seems to have infinite money to pour into Vegas slot machines.

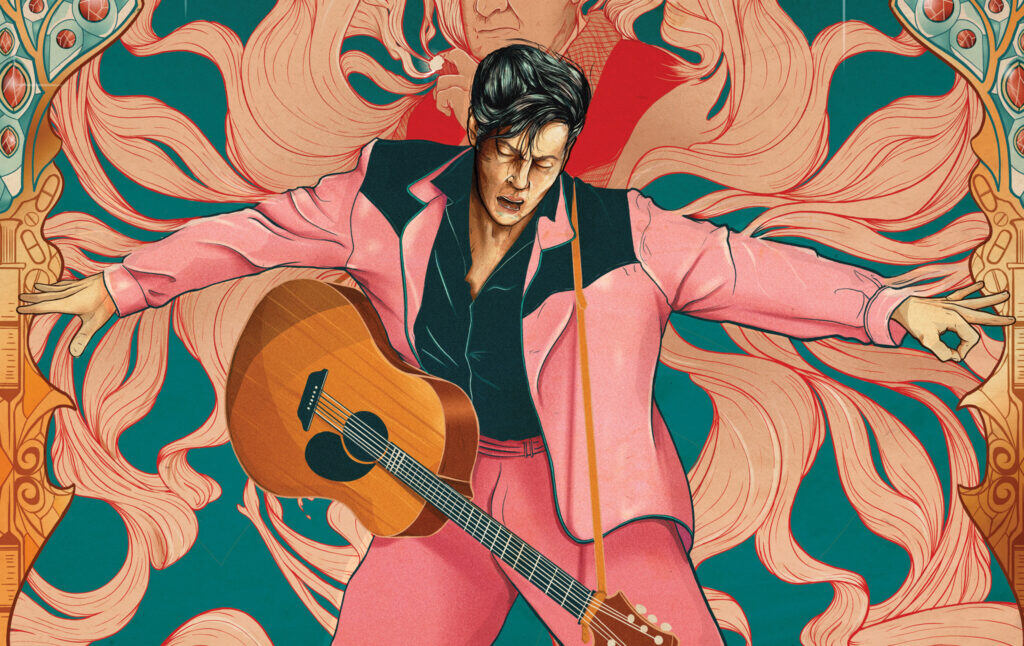

Elvis is a wild alchemy of at least a hundred years of popular culture, overlaying stories we know onto the Elvis Presley story to make us realize we don’t know this story at all. All this is in the key of queer fantasia, relentlessly committed to tacky, bad-taste too much. It’s glitzy and kinetic, unerringly taking the big swings in a way that’s thrillingly disorientating. (There is split-screen in this movie that would make Brian De Palma throw up.) James Franco once described himself as “gay in my art and straight in my life,” and that’s gross and offensive and absurd, but it might actually be true about Baz Luhrmann, whose films—from Moulin Rouge! (2011) to Romeo + Juliet (1996)—invariably have a distinct gay sensibility. Part of this is his maximalist camp aesthetic; part of it is his films’ attention to the female and queer gazes. In between montages of gaudy excess, Elvis keenly observes how young women and occasionally young gay men—including a segregationist senator’s son—experience Elvis as an object of sexual desire. His androgyny, all-pink suits and black eyeliner, is a key part of this, which disrupts the assumed hierarchy of masculinity. This, the film suggests, is part of why the establishment viewed him as dangerous.

The main reason they see Elvis as dangerous, though, is his racial transgression. He’s a white man making Black music. He dances the way that, as he says himself, “colored singers” have been dancing for years. Contemporary conversations about Elvis Presley and race generally take their cue from Public Enemy—motherfuck him and John Wayne!—and apply some variant of the cultural appropriation rubric to position Presley as stealing rock ‘n’ roll from the Black artists who created it. There’s merit in this, of course: Elvis’ success, like Eminem’s decades later, is inseparable from the whiteness that made him a saleable commodity in the white suburbs in a way the Black artists who created the genre would never be. Elvis’ success, unlike Eminem’s, essentially led to a total white takeover of a Black-created genre.

The film’s soundtrack exploits precisely the gap between rock ‘n’ roll’s whitewashed legacy and hip hop’s: Elvis is full of modern music, particularly hip hop, alongside period-appropriate blues and rock ‘n’ roll, juxtaposing Black-created genres that were totally taken over by white artists with a Black-created genre in which, to some extent, Black artists are still the predominant creators. When Elvis walks through Beale Street, we hear Big Mama Thornton sing “Hound Dog,” which she originated and Elvis recorded much more famously. But Thornton’s “Hound Dog” builds into Doja Cat’s “Vegas,” which samples Thornton in a fizzily hooky rap song. It’s a reassertion of “Hound Dog” as Black in origin, and underlines it by tying it forward to today’s Black music genres. (Doja Cat is biracial; her mother is Ashkenazi Jewish, her father is Zulu.)

Elvis turns around Presley’s reputation as a thief of Black music by presenting us with another group of people outraged that a white man would make Black music: white segregationists. Southern Democrat Mississippi Senator James Eastland leads a charge to have him boycotted, banned, jailed—anything to stop his wiggling hips and African beats from corrupting the purity of white children. “Surely hip-hop was never a problem in Harlem, only in Boston,” Eminem once rapped, “After it bothered the fathers of daughters startin’ to blossom.” The same applies to rock ‘n’ roll. Though Elvis—certainly in the early part of his career—doesn’t do or say anything political, his very existence flouts the basic tenets of white supremacy and segregation. Even though he performs to segregated crowds, even though he never bridges the gap between the Black and white worlds even as he moves with ease between them, his music belies the idea that it is possible or desirable to truly segregate culture. And white authorities would lock him up before they’d sit back and let that take hold.

After failed attempts at rebranding his client as the “new Elvis” in a tuxedo, the Colonel persuades the senator to enlist Elvis in the army instead. Elvis is shipped off to Germany, leaving his mother to die of a broken heart (and alcoholism). In Germany Elvis meets Priscilla, the daughter of his commanding officer, and falls in love. After Elvis’ mother dies, Priscilla becomes the only meaningful opposition to the Colonel in Elvis’ life, the only force tugging him out of the Colonel’s orbit. Trouble is, the Colonel’s gravitational pull is too strong, too all-encompassing. She’ll never succeed.

On his return to the States, Elvis launches a movie career, each film cheaper and more slapdash than the one before. By 1968, his career is “in the toilet.” The Colonel has arranged for him to make a TV Christmas special: he has gone from being threatened with arrest for the way he moved his hips to making the kind of thing where he’d wear a Christmas jumper and sing “Here Comes Santa Claus” by the fire. The world around him is alight with revolution—social movements for civil rights and against war, radical changes in how Americans understand themselves and their place in the world—while Elvis hasn’t just stood still but has gone backwards. He’s a relic of a bygone age.

Elvis, impressed with his work with James Brown and the Rolling Stones, recruits Steve Binder to direct the special. It’s a simultaneous effort to return to a golden past and Elvis’ first real foray into the present. So much of what is happening in the world—all the changes that have left him behind—are things he should have been intimately a part of. Didn’t he inspire every British Invasion band to pick up a guitar? Didn’t he threaten the segregationist South way back when?

The Colonel tells us that Elvis had been “brainwashed” by “hippies,” who convinced Elvis he was one of them. The film suggests the opposite is true: that, despite his political instincts towards lefty liberalism, Elvis was pushed by the industry and the Colonel into a conservative box the confines of which he always chafed against. He is devastated by the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr.—who Elvis says “always spoke the truth”—just five miles from Graceland, and, while they’re preparing the special, Robert F. Kennedy. “A tragedy,” the Colonel says, “But it has nothing to do with us.”

“It has everything to do with us!” Elvis counters. He wants to speak out, to make a statement, to do something, anything, but the Colonel is having none of it. Elvis Presley does not make statements. He sings “Here Comes Santa Claus” and advertises Singer sewing machines.

Binder takes creative control of the special, which involves in no small part allowing Elvis a measure of creative control for the first time in years. Binder wants to take him back to Beale Street, to dress him in leathers, to have him perform to a live audience for the first time in years. There’s nothing Christmassy about it. The sponsors and TV executives are furious and threaten litigation. The Colonel assures them that Elvis will sing “Here Comes Santa Claus” in a snow scene. He berates and belittles Elvis, telling him that the crowd cheered only because there was a bright sign flashing “Applause.” That grunting incoherently in a leather outfit does not impress anyone. That his precious Martin Luther King Jr. thought rock ‘n’ roll contributed to juvenile delinquency. That he will sing “Here Comes Santa Claus,” and that’s that.

The next day, everything is set: a snow scene, complete with snowmen and dancers in winter knits. The Colonel watches on with the pleased execs and sponsors, happy to see something Christmassy afoot. Then, right as Binder calls action, the camera spins around to reveal Elvis standing in front of a giant sign lit up with his name. He sings “If I Can Dream,” a tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. It’s an incredibly powerful moment: the little boy who felt the music move through him in a gospel revival, the young man with Beale Street stars in his eyes, part of whom died along with his mother, gets to say the things he believes in with the gifts God has given him. It’s like getting a glimpse of a world where Elvis has control over himself and his art, free from the confines the Colonel wraps him in—a world where he has the chance to grow and develop and speak. His arm swings back and forth, a big, unconscious movement, because, like the minister said when he danced as a boy, he’s with the Spirit.

Elvis’ connection to Black culture in the movie is authentic, the inevitable product of a childhood steeped in it, surrounded by it. But there’s always a gap, a danger his whiteness insulates him from, a privilege it affords him, a thoughtlessness only possible when the dominant culture is made up of people who look like you. Elvis counts Black artists—B.B. King in particular—as dear friends, but the “Memphis mafia” he surrounds himself with is all white. He corrects white journalists who dub him the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll by bringing out the real king, Fats Domino, but as the film’s text epilogue tells us, it’s Elvis who becomes the best-selling individual artist of all time. King is killed five miles from Graceland, but Elvis Presley does not make statements. He sings “Here Comes Santa Claus.”

Elvis’ proximity to blackness made him dangerous, so the Colonel has spent all these years steering him away from it. While his whiteness meant he didn’t have to join the fight for Black people’s civil rights, the fact that his roots are in Black culture means that he should join the Black civil rights movement. By paying tribute to Martin Luther King Jr., Elvis reasserts his proximity to Black culture and makes that proximity politically potent. It’s not that singing a song is some grand political act, but in a show that pays tribute to his roots, Elvis shucks off feigned neutrality. When he sings “If I Can Dream,” he’s staking out his position. He’s joining the fight.

Or he tried to. The special is a huge success—it quickly becomes known as the Comeback Special—and the Colonel, naturally, takes credit: it was his idea, after all. Offers are pouring in, and for the first time in a long time, it looks like Elvis has the upper hand in his relationship with the Colonel. He can go anywhere, or do anything. He wants a world tour. He has never been outside the United States, other than when he was in the military.

The Colonel presents him with a proposal. He’ll play a series of shows at the International Hotel in Las Vegas. The hotel will pay for everything. It can be as big and expensive as it needs to be. The money he makes can be used to fund the world tour. There’s no risk. You pray for Elvis to see through him, to see it as another of the Colonel’s manipulations, to run away while he still has legs to carry him. But he doesn’t. “Snowman strikes again,” he says, flashing a toothy grin, locking himself in.

The Vegas shows are both the film’s ultimate representation of Elvis’ talent and, in the end, its most skin-crawling horror. Initially, Elvis is excited to be putting the show together. He recruits musicians and vocal groups he admires, and carefully instructs them in a way that shows that Elvis’ involvement with his music went much further than just singing the song, no matter what the writing credits have to say. “This ain’t no nostalgia show,” he says, transforming his first hit—“that’s All Right, Mama”—from a straightforward guitar ditty into a sprawling epic. He didn’t write it, but it feels like it’s being composed before your eyes. He can’t wait for the whole world to see this show.

But the Colonel negotiates for Elvis to come back and do this show at the International every year. Part of the deal is that all the Colonel’s gambling debts are written off, of course. What started as a thrilling creative outlet for Elvis becomes, as he tells his father, a “mausoleum.” No world tour. Nothing but this, here, forever. He sings “Suspicious Minds,” and it’s hard to miss the resonance: he’s caught in a trap, can’t get out.

He yells on stage that Colonel Parker is an alien—meaning he’s an undocumented immigrant—and it’s easily written off as drunken rambling, as if the Colonel is going to fly away in his spaceship.

Priscilla leaves him, citing his addiction to painkillers and that he’s barely there anymore. “When you’re 40 and I’m 50,” Elvis tells her sadly, “We’ll be back together, you’ll see.” He never makes it to 50.

The Colonel’s abuse of Elvis—financial, psychological, professional—is devastating to behold. He trapped Elvis, exploited him, isolated him, and made him believe he needed the Colonel as much as the Colonel needed him. But the Colonel’s abuse is also just a particularly flagrant example of the abuse systemic in the music industry, ranging from Taylor Swift being denied ownership of the master recordings of her first six albums to the boyband Why Don’t We’s management holding them hostage in their home and restricting their food. TLC went bankrupt at the height of their fame: “I will never forget the day we were millionaires for literally five minutes,” T-Boz told The Guardian two decades later, “Because the cheque was written to us and we had to sign it over, back to [Pebbles, their former manager]. But we won’t get into that since we’re still in a lawsuit.” Kesha was emotionally, financially, and sexually abused by producer Dr. Luke for years, and lost her lawsuit to be let out of their contract. Almost half of female members of the Musicians Union in the U.K. have experienced workplace sexual harassment. There are significant racial disparities in music royalty payouts, with artists of color being given unfavorable contracts. Britney Spears. Brian Wilson. Untold thousands of anonymous others. Ones we might know someday—the Colonel’s financial abuse of Elvis only came to light after Elvis’ death, after all—and ones we’ll never know.

And everyone knows this. It’s a trope core to the music biopic. In Elvis, Baz Luhrmann makes the abuse that drives the music industry feel hellish again—it’s not a point to hit in a formula, it’s visceral and shocking. It’s one of the myriad ways he elevates the biopic formula to fresh heights: a glittering mirror ball of a film that takes hold and pulls you through the fizziest joys and heart-breaking sorrow.

The Colonel dies impoverished and alone. Elvis lives forever.