The Afterlives of Che

What can the Left learn from the life of one of the twentieth century’s most visible political icons?

At the culmination of a months-long manhunt by the Bolivian Army and the CIA, Che Guevara’s last words were simple. “Shoot, coward,” he cried into the face of his executioner. “You are only going to kill a man.” Seeing himself as a small piece of a larger socialist project, the guerrilla warrior apparently had no lingering interest in his own life (or at least, an unconquerable flair for the dramatic). All that Che cared to envision on death’s doorstep was the immortality of an international revolution, one that would bring an end to Yankee imperialism and usher in an age of global communism.

Or so we’re told.

Jon Lee Anderson, the author of Che: A Revolutionary Life and long considered Che’s authoritative biographer, admits that this scene is likely more legend than fact. In a text otherwise notable for its deep research and intensive reflections on the Argentine’s personal and political legacy, Lee’s decision to conclude his biographical behemoth with a scene based more on myth than fact reflects the height to which Che has ascended in the popular consciousness, for leftists and nonleftists alike. But what exactly does the face of the Argentine revolutionary represent, and what can we learn from his life and death?

For some, Che represents revolutionary potential, a direct symbol of the political ideologies the guerrilla fighter espoused during his life. Historical admirers range from writers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Susan Sontag to bona fide revolutionaries like Stokely Carmichael and Nelson Mandela, Che’s bedfellows in armed struggle. In this regard, Che seems very much a figure of his time and place, when guerrilla warfare appeared the only effective tool to challenge the reigning dictatorships of South America and the violent power of U.S. Imperialism.

Beyond his identity as a socialist revolutionary, Che has also taken on a more general historical status, particularly in the Latin American countries where he spent significant time. In his native Argentina, numerous high schools bear his name, while some campesinos (Spanish for a rural peasant- farmer) in Bolivia, the site of his final guerrilla campaign, revere him as San Ernesto (Saint Ernest), surely influenced by his resemblance to Western cultural depictions of Jesus Christ. Nowhere is he more revered, however, than in Cuba. In the country where his myriad efforts and influence helped establish the Castros’ socialist state, Guevara seems to have taken an uncritical spot in the pantheon of historical figures, similar to the way the United States’ Founding Fathers are revered. Che graces the head of every 3-peso banknote, and young students recite “Seremos como el Che (We will be like Che)” daily, just as U.S. students grow up reciting the Pledge of Allegiance each morning before school.

Others on the broad left talk of Che in more measured terms, qualifying any praise with criticism or even suspicion. In an assessment of Che’s legacy in Jacobin (itself a kind of crib sheet for his excellent book The Politics of Che Guevara), Cuban-American scholar Samuel Farber called Che “an honest and committed revolutionary” who nonetheless possessed a “monolithic conception of a type of socialism immune to any democratic control and initiative from below.” On the other hand, some on the right consider Che Guevara nothing but a mass murderer. Referencing the legend of his demise, Álvaro Vargas Llosa of the libertarian think tank The Independent Institute wrote, “Guevara might have been enamored of his own death, but he was much more enamored of other people’s deaths.”

More than half a century after Che’s execution at the hands of the Bolivian Army and the CIA, awareness of his revolutionary accomplishments and failures has paled in comparison to the attention he receives as a pop culture icon. Countless novels, biographies, films, and even musicals depicting the revolutionary constitute the broader pantheon of Che, all on top of a wealth of traditional scholarship. There were even plans to market a Che-themed perfume, though it appears to have been canceled upon criticism from the Cuban government— a fitting fate for a perfume named after someone who frequently refused to bathe as a function of a kind of socialist asceticism. But the most significant vehicle for Che’s legacy is without a doubt the omnipresence of his face.

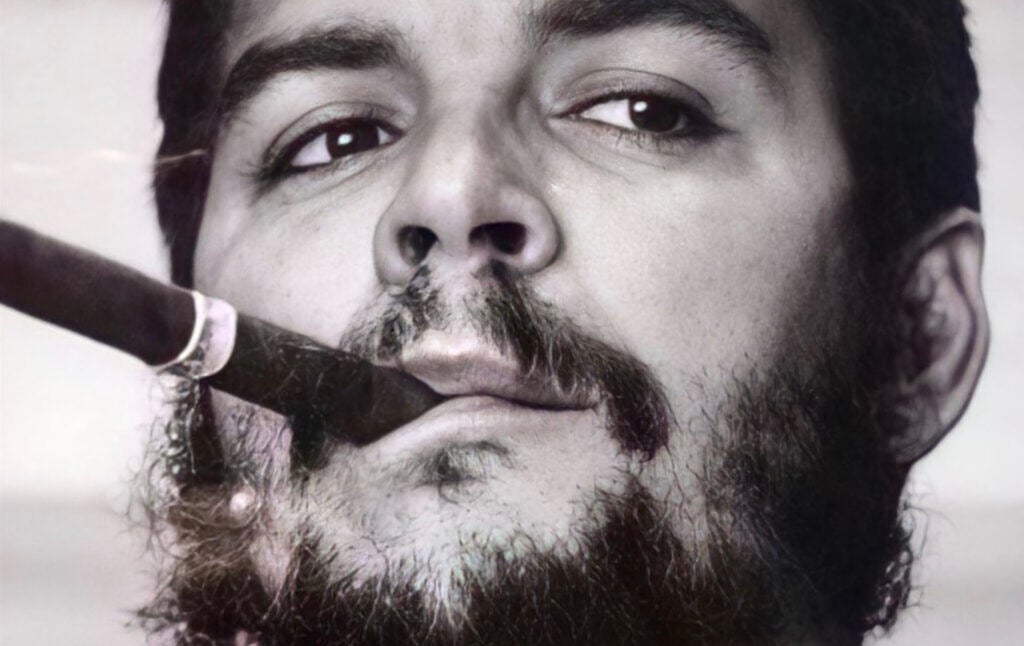

Taken by Cuban photographer Alberto Korda, Guerrillero Heroico is surely one of the most ubiquitous photographs in the history of the medium. The subject of art exhibits, the source of endless parodies, and even the inspiration for a Madonna album cover, the image graces everything from street art to T-shirts, its recognizability having long since transcended its subject’s rich legacy. Some invoke the image literally, plastering it on protest signs or graffitiing it under bridges as a symbol of left-wing dissent. For many, however, the Comandante is hardly even a political figure, more associated with the notion of rebellious youthful adventure than with revolutionary struggle. Perhaps some who see his face don’t even know who he was or what he stood for, content to let symbology transcend history and biography (I once saw a T-shirt with Che’s silhouette and the caption “I have no idea who this guy is”). Che decried both individual veneration and the culture of capitalist commodification, yet the system he died fighting seems to have done a fine job profiting off his image, just as the image of avowed communist Frida Kahlo has been packaged and marketed to consumers of #girlboss aesthetics. Nonetheless, his omnipresence decades after his death remains a testament to Che’s enduring power as a symbol of revolution and dissent.

So what can the modern Left learn from the life of the twentieth century’s most visible political icons—a man who lived only to age thirty-nine? Is he merely a figure of his historical moment and an example of the limits of armed struggle, or do his life and example offer some kind of deeper insight into the socialist struggle?

“I believe in the armed struggle as the only solution for the people who fight to free themselves and I am consistent with my beliefs. Many will call me an adventurer, and I am, but of a different type, of those who put their lives on the line to demonstrate their truths.”

-Che Guevara, letter to parents

Born in Rosario, Argentina in 1928 to a middle-class family, the young Ernesto Guevara counted girls and rugby among his primary interests. A chronic asthma defined much of his childhood, just as it would eventually challenge his stamina on later guerrilla campaigns. When his asthma kept him off the rugby pitch, Ernesto read voraciously, imbibing everything from the works of Walt Whitman and William Faulkner (Guevara would later posit that the United States’ literature was the empire’s only redeeming quality) to the economic and political philosophies of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, both of whom he would later go on to venerate.

When he decided to study medicine, his personal vision for his medical career demonstrated a grandiosity similar to the way he would later direct his political efforts. “I dreamed of becoming a famous researcher,” he wrote, “of working indefatigably to find something that could be placed at the disposition of humanity.” It’s clear that from an early age, the future warrior had grand ambition and a significant ego, but he hoped to channel both into changing the world for the better. So how did Ernesto, a middle-class asthmatic medical student in love with literature and science, turn into Che, the famous communist revolutionary bent on armed struggle, which he believed was the only way to topple Yankee imperialism and pave the way for a global socialist order?

His transformation began when he decided to fulfill another ambition: the urge to explore. In January 1953, the 23-year-old took time off from his medical studies to travel his home continent with his friend Alberto Granado, a 29-year-old biochemist who also longed for adventure. A journey taken by a middle-class student like Guevara could have been self-indulgent. Guevara and Granado, however, spent their time not in comfortable accommodations but in humble places, encountering humble people. Beginning in Buenos Aires, the duo spent nine months traveling in haphazard fashion up the continent, including a multi-week stint volunteering their scientific and medical talents at a leper colony in Northeast Perú. Along with the ubiquitous representation of Che’s face, details from these travels form the basis of the Che legend as depicted in the 2004 biopic The Motorcycle Diaries (which I highly recommend, if only to see heartthrob Gael García Bernal and the beautifully shot scenes of the young vagabonds riding through rural Chile or traipsing through a tourist-free Machu Picchu).

Guevara would go on to recount his experiences in his memoir Notas de Viaje (published in English as The Motorcycle Diaries and the primary basis for the film). In an oft-quoted passage, Guevara writes of an encounter with a campesino couple looking for work. The couple experienced persecution as members of the Chilean Communist Party:

“The couple, numb with cold, huddling against each other in the desert night, were a living representation of the proletariat in any part of the world. They had not one single miserable blanket to cover themselves with, so we gave them one of ours and Alberto and I wrapped the other around us as best we could. It was one of the coldest times of my life, but also one which made me feel a little more brotherly toward this strange, for me at least, human species. … The communism gnawing at his entrails was no more than a natural longing for something better, a protest against a persistent hunger transformed into a love for this strange doctrine, whose essence he could never grasp but whose translation, “bread for the poor,” was something which he understood and, more importantly, filled him with hope.”

On one hand, the sympathy Guevara expresses in this passage is admirable. For the young adventurer, the victims of capitalism no longer existed as abstract referents in the Marx and Engels texts he had already devoured. He saw actual people who would stand to benefit the most from—and who had joined a movement fighting for—the worldwide political revolution that Guevara had already begun to believe was necessary. On the other hand, Guevara’s assumptions about the campesinos’ grasp of communism could be seen as condescending. By saying that the campesinos “could never grasp” the “essence” of communism, did he mean that material or intellectual deficits prevented them from understanding communist theory? Or did he just mean that their physiological needs gave them an understanding of “bread for the poor” that was just as instructive as any complex theory?

In any case, Guevara’s observations represent a turning point in his personal development, whereby his experiences in the real world confirmed and deepened his understanding of his developing political beliefs. Guevara was already familiar with and an adherent of Marxist theory, but it was his motorcycle journey that laid the true groundwork for the revolutionary he would become. “The person who wrote these notes died upon stepping once again onto Argentine soil,” Guevara writes in the forward to Notas de Viaje. “The person who edits and polishes them, me, is no longer. At least I am not the person I was before. The vagabonding through our ‘America’ has changed me more than I thought.”

Guevara went on to obtain his medical degree upon his return to Buenos Aires, but he did not pursue a career as a medical researcher like he had planned. After graduating, he traveled more through Latin America before settling for a time in Guatemala, where he was impressed with the ongoing agrarian reforms of President Jacobo Árbenz. His time in Guatemala gave him a taste of what he already viewed to be the greatest obstacle to the revolution: U.S. corporate and military power. In a pattern familiar to students of U.S. imperialism, the Árbenz government attempted to seize land belonging to the United Fruit Company for more egalitarian redistribution, only to be countered by a multi-pronged CIA operation that ended in a coup. (It was no coincidence that Eisenhower’s Secretary of State John Foster Dulles was an attorney for and stockholder in the United Fruit Company.) Emboldened upon viewing imperialism in action, Guevara made his way to México to begin training as a guerrilla. There, he met two young men planning a movement to overthrow Cuba’s repressive dictator, Fulgencio Batista. Their names were Fidel and Raúl Castro. Guevara recognized revolutionary potential in the Castros’ bristling 26th of July Movement and agreed to join them. Seeing Cuba as an ideal opportunity for a vanguard communist state and the potential testing ground for his notion of guerrilla praxis, Guevara wanted to be at the forefront of the socialist struggle in Latin America. He went on to find his revolutionary stride in the hills of the Cuban Sierra Maestra, the launching point for an armed movement that battled the Cuban army and eventually ousted Batista’s dictatorship. It was also in Cuba that Ernesto Guevara took on the moniker “Che,” a nod to an Argentine interjection that translates roughly to “Hey” or “Look.”

Given the title of comandante and a place as Fidel’s right hand man, Che became known within his guerrilla forces for two traits above all: for demanding extreme discipline from his fellow combatants, and for working to expand their literacy. For every anecdote of his teaching a young Cuban to read, there’s another one of him punishing his soldiers for negligence, insubordination, or dissent—sometimes fatally. Anderson highlights a particularly chilling excerpt from Che’s diaries where the comandante hardly hesitated in executing a guerrilla turned traitor named Eutímio Guerra. “The situation was uncomfortable for the people and [Eutímio],” Che wrote, “so I ended the problem giving him a shot with a .32 [caliber] pistol in the right side of the brain, with exit orifice in the right temporal [lobe]. He gasped a little while and was dead.” Che was determined to usher in communism at any cost; if those who stood in the way had to die, so it would have to be. Che retained this attitude during the construction of the new Cuban government after Batista’s ouster, during which he ordered the executions of countless rank and file members of the preceding government. For Che, killing was just a part of the job, a textbook example of an attitude where ends justify the means.

Che’s sizable body count—in the hundreds, by some estimates—remains his critics’ greatest fodder, and for understandable reasons. Che’s dogmatic commitment to violence was excessive and unjust, a hypocritical blind spot for someone who claimed to believe in the imperative of a just world. Contrary to popular right-wing and liberal talking points, however, Che does not appear ever to have killed any “innocent” people, if we take that term to mean civilian bystanders. “I have yet to find a single credible source pointing to a case where Che executed ‘an innocent,’” said Anderson, whose research writing Che spanned three years and various diverse sources. “Those persons executed by Guevara or on his orders were condemned for the usual crimes punishable by death at times of war or in its aftermath: desertion, treason, or crimes such as rape, torture, or murder.” In Che’s view, all his (numerous) victims were direct political or military targets, individuals whose deaths were necessary casualties of a just war, the excesses of which would ultimately be vindicated by the new world they would help build. In this vein, Che advocated violence not as a sadistic show of state force or a display of personal power, but as a revolutionary tool, one that he asserted was the only true method by which revolutionaries could usher in a just and egalitarian world.

In his introduction to the graphic novel adaptation of his Che biography, Jon Lee Anderson aks, “How do we explain Che to youngsters who, unlike those of us who lived through the sixties and seventies, can’t imagine picking up a gun to fight for their ideals?” To truly understand Che’s violent approach, however, it is important to understand the historical context. Decades of organizing and electoralism throughout Latin America had only drawn the violent retaliation of local and international elites. Furthermore, Che had seen firsthand in Guatemala that even the most tepid land reforms of the decidedly noncommunist Árbenz government would be fought tooth and nail by both the local bourgeoisie and the powers of Yankee imperialism. Particularly to generations of Americans who grew up learning whitewashed glorifications of the Civil Rights Movement’s nonviolent civil disobedience, Che’s commitment to the avenue of armed struggle may seem outdated or questionable. But in the context of the Cold War, armed struggle—with all its concomitant excesses—seemed the most realistic and effective liberatory tool in the face of increasingly militarized capitalist empires. This outlook places Che squarely among numerous contemporaneous revolutionaries, people like Fred Hampton of the Black Panthers and Nelson Mandela of the African National Congress, himself a revolutionary figure whitewashed in the years after his release from prison and election to the South African presidency. Che’s violence is criticizable, deplorable even, but any assertion that Guevara was nothing less than a bloodthirsty mass murderer constitutes an argument completely bereft of historical or ideological context. Instead, his conviction recalls the words of poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who in 1958 wrote, “I am waiting/for the war to be fought/which will make the world safe/for anarchy.” Rather than wait, Che took it upon himself to attempt to wage that war. If he was successful, he might prepare the world for justice and peace.

Beyond his commitment to armed struggle, Che was similarly ideologically rigid. Like many other orthodox Marxists of the era, Che considered the great sociologist a scientist whose conclusions were tantamount to unbreakable laws in a reverence unmatched even by the loudest voices on Leftist Twitter. In 1960, Guevara wrote:

“There are truths so evident, so much a part of people’s knowledge, that it is now useless to discuss them. One ought to be ‘Marxist’ with the same naturalness with which one is ‘Newtonian’ in physics, or ‘Pasteurian’ in biology, considering that if facts determine new concepts, these new concepts will never divest themselves of that portion of truth possessed by the older concepts they have outdated.”

In his adherence to Marx’s notion of scientific theory (or “scientific socialism”), Che rejected other variations of socialism. For Che, a socialist world would only ever look one way, and any other experiments were doomed to fail. His biggest blind spot in this regard was his disdain for workers’ strikes within a communist state and for any efforts to increase collective democracy. As far as Che was concerned, there was no need for other forms of worker power, such as unions, in the context of a Marxist workers’ state. Antagonism towards the state, in Che’s view, was the pinnacle of contradiction. As with his violent approach, Che’s dogmatic commitment to Marxism-Leninism makes more sense within its historical and regional context, where the communist states of the USSR and China seemed to be the most reasonable alternatives to the overreach of American imperialism and the western capitalist order. For Che, a truly robust democracy would do more harm than good; democracy was a distraction from the hard work required to build and maintain an egalitarian order through a strong workers’ state. (For a more detailed analysis of Guevara’s politics, see Farber’s The Politics of Che Guevara: Theory and Practice.)

Ultimately, perhaps Che’s biggest flaw was his voluntarist outlook—the belief that the primary, if not sole, obstacle for the establishment of communism would be the will of the people and the State. If the people fought and worked hard enough, Che believed, communism would come naturally, no matter the external factors. In this vein, Che advocated personal self-sacrifice in service of the broader collective as the quickest road to a functioning socialist society. He encouraged Cubans, for example, to give up their Saturdays to work for free in the factories or fields as a kind of donation to the revolution. Always practicing what he preached, he became known among Cuban workers for volunteering his labor, a model of the socialist ethic he espoused. A true revolutionary, he thought, would be happy to subvert their individual desires in service of the greater socialist project— an attitude he apparently demonstrated in his final moments, if he truly did say, “You are only killing a man.”

For Che, the early success of the revolutionary movement in Cuba was an impetus to export armed struggle across the world. He hoped to repeat his success starting in the Congo, but when that failed he moved on to Bolivia, where he ultimately met his end. You could blame his failure in Bolivia on numerous external elements, most obviously the lack of cooperation from the Bolivian Communist Party and the presence of the CIA and the U.S. Army Rangers, who wanted to prevent Che from turning Bolivia into one of the “two, three or many Vietnams” that Che hoped would “flourish throughout the world with their share of deaths and their immense tragedies, their everyday heroism and their repeated blows against imperialism.” But Che’s voluntarist outlook, where he thought he could simply pop up in Bolivia and incite a revolution among the local proletariat merely through his presence, ignored the myriad complex factors and regional particularities that defined Bolivia—his guerrilla unit’s ignorance of local Indigenous languages, for example, was a real impediment to organizing the Bolivian proletariat. Che was unable to understand why the local campesinos didn’t trust him, some of them even going so far as to turn into informants. Though his espoused strategies had worked in Cuba with the Castros, he was unable to export them elsewhere. He was captured and executed on October 9, 1967.

Since his demise, the notion of warfare as a path to revolutionary power has become a leftist praxis subordinate to the nonviolent civil disobedience methods of movements like Black Lives Matter or the electoralist bent of politicians like Bernie Sanders or Jeremy Corbyn. In this sense, Che’s revolutionary legacy may seem frozen in time, one whose vision and ambition remain admirable but whose strategies have been relegated to the past, more as anecdotes than models. From this vantage point, it would seem easy to relegate Che’s memory to movies and T-shirts, or books and long-form articles, rather than to consider him a real revolutionary inspiration for modern times.

To write off Che completely, however, would be to write off his greater example of commitment to justice. Take, for instance, the roots of his socialist ethic, which ultimately stemmed not from theoretical knowledge or political analysis but from a deep love for humanity and a hatred of injustice. “At the risk of seeming ridiculous,” he wrote in one of his manifestos, “let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality.” Or consider his final letter to his children, which he ended with one last piece of advice: “Above all, try always to be able to feel deeply any injustice committed against any person.” Say what you will about his tactics, his dogma, or his ego: those are the words of someone who knew the shape of his heart, someone who wanted himself and others to bear witness to human suffering in the hope that such acts would become a catalyst for change.

It is undeniable that Che Guevara lives on. But which Che? Is it the hopeful young adventurer who opened his heart to victims of brutal injustice throughout Latin America and the world? The voluntarist guerrilla fighter whose strategies made sense in context but now seem largely outdated? The rigidly ideological intellectual who refused to tolerate dissent, even among the guerrillas who fought and died at his side? Does Che remain a symbol of principled anti-imperialism, or have the ubiquitous, commodified images of Che—the dorm room posters and T-shirts of angsty college students like me—ultimately superseded his political and personal legacies?

Let’s return to Che’s final moments, when he awaited execution in a Bolivian schoolhouse. Perhaps he wasn’t thinking of the immortality of the communist cause but was instead pining for his children, or craving a final cigar. We will never know for sure. The legend of his final moments persists, however, precisely because of what it says about the Left. In our best and most honest moments, leftists recognize that the projects of equality, freedom, and justice will always be bigger than any one person, no matter how large some of their proponents may loom. In this instance, the causes that Che fought for outweighed him. It doesn’t matter that Che died before his dream of an egalitarian world could be fulfilled. All that matters is that such a dream lives on because figures like Che declared that it would.

What if, then, instead of treating Che as a symbol of leftist idealism, we began to recognize his example as a lesson for the present and the future? On one hand, we can be more open-minded, more self-critical, less dogmatic than he was, remembering that the socialist struggle will always be variable, and certainly never easy. More importantly, however, we should follow the spirit of his example, if not the letter, daring to love our fellow humans, daring to dedicate our lives and souls to their uplift, and, above all, daring to dream big and bold in the face of a world that will only change if we make it.