Most of us would like to think of ourselves as being immune to the power of advertising. The idea that we as consumers are mere marionettes, dancing at the whims of our corporate overlords, is an uncomfortable image.

However true this image may be, our discomfort with it alone says a lot about our relationship with ads. That is, we try not to take ads at face value. We know they do not truly represent goods and services as they are, but rather, as what corporations want us to believe.

Let’s recall Pepsi’s infamous “Live for Now” commercial featuring Kendall Jenner. Pepsi was framed, here, as not just a good can of soda but some kind of sociopolitical panacea, cooling ambiguous unrest between cops and protestors, with Jenner as the one brave soul to make the peace offering. The commercial, which elevates soda to a near-spiritual plane, serves as a fantastically clear example of shameless corporate myth-making.

But not all corporations are so flagrant. In fact, some are so subtle that their advertising might even be mistaken for corporate myth-busting.

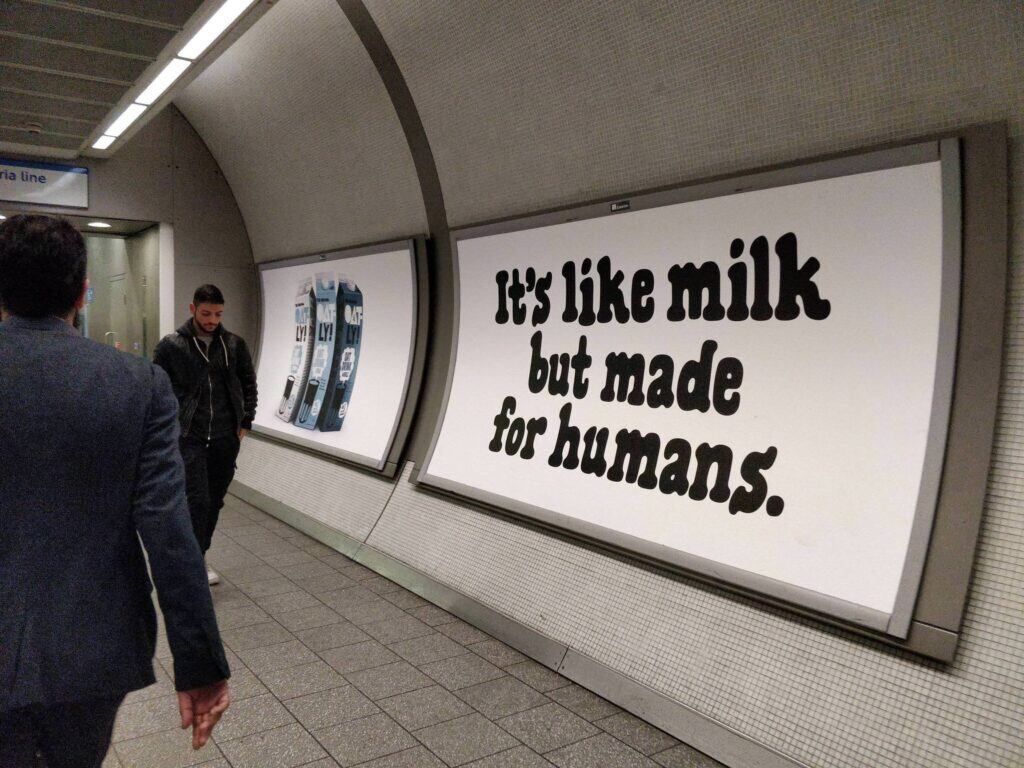

Several weeks ago, I started noticing some of the new ads put out by Swedish vegan food brand Oatly. One of them pictures a small carton of oat milk against a plain white background, with simple black text that reads, “Posters don’t have feelings, so you don’t have to pretend that you are interested.”

Suffice it to say, I was interested. This is because ads–especially ones like “Live for Now”– are generally lurid, desperate intrusions that practically (if not literally) scream for your attention. But Oatly’s seemed refreshingly self-aware–self-loathing, even! Finally, I thought, a megabrand that properly hates itself. But I caught myself before buying into this myth any further.

Corporations, despite what advocates of corporate personhood might have you believe, cannot properly hate themselves. This is because corporations cannot “feel” anything at all. They are of course not motivated by normal human emotionality like empathy or sadness or self-loathing; they are motivated by profit. That the ad industry could trick me into believing otherwise, even for just a moment, is a testament to its ever-adaptive nature. And Oatly is a great example of how––in a time when the American public is more critical of mass consumerism and advertising than ever––corporations have managed yet again to adapt.

For those new to the name, Oatly is a Swedish vegan food brand that makes oat-based alternatives to dairy products like ice cream, milk, and yogurt. It formed in 1994 as a startup that grew out a research project at the University of Lund. As one of the first companies to commercialize oat milk, Oatly was initially relegated to shelves for people with dairy allergies. “At first, nobody wanted it,” CEO Toni Petersson told The New Yorker. But when Petersson joined the company in 2012, along with Chief Creative Officer John Schoolcraft, Oatly rebranded itself as a “challenger company” dead set on “shaking things up.” It claimed a fresh-faced vision of health, authenticity, and sustainability.

After capturing a sizable market share in over thirty countries, Oatly expanded to North America in 2016. By then, alt-milk was already a $7.3 billion industry, so the company had to be crafty: Instead of putting its products in major retailers, Oatly launched a “business-to-business” marketing campaign, mainly targeting baristas. It sent samples to high-end coffee chains like Intelligentsia, who sang Oatly’s praises so Oatly didn’t have to.

In 2018, Oatly opened up its first American processing plant in Malville, New Jersey. By 2019, Oatly alone accounted for 36.4 percent of America’s plant-based dairy sales. Shortly thereafter, private equity hawks began to flock to the brand. Just this year, for example, Oatly received a $200 million investment from Blackstone, a global investment bank led by top Trump donor Stephen A. Schwarzman. Oatly is now available in approximately 7,000 coffee shops and grocery retailers across the U.S and is reportedly planning its IPO with Goldman Sachs, hoping to rake in $400 million of revenue by 2021.

Although Oatly-the-company now has a budding relationship with Wall Street, Oatly-the-brand still prides itself as being subversive amongst its peers, particularly by way of its marketing and advertising strategies. The marketing strategy relies upon an in-group approach by planting its products in cafes, where baristas share the brand with customers, who will inevitably buy its products in retail stores. In other words, instead of “shameless” self-promotion, Oatly capitalizes off of a more “organic” word-of-mouth cool factor.

The advertising strategy is slightly different, but it goes against the grain as well. In 2014, Oatly ran the slogan: “Milk, but made for humans.” After Swedish milk lobby LRF Mjölk sued the company for implying that cow’s milk was not healthy for humans (and won), Oatly published the entire 172-page lawsuit on its website for a retrial, this time by public opinion. In 2019, Oatly took out a full-page ad in The Guardian calling on the food industry to lower its CO2 emissions. The ad demanded, “Show us your numbers.”

Oatly’s Chief Creative Officer has spoken ad nauseum about the so-called “fearless” ways in which Oatly is flipping traditional advertising on its head in service of a more “real” approach:

“[Consumers] are easier to reach when you treat them as humans and not as segmented target groups plotted into a quadrant on a powerpoint graph. If you believe that humans don’t really need brands, that they are looking for something more real, then you will end up working to give them something more real instead of just creating marketing campaigns to sell products.”

The mawkishness aside, Schoolcraft could be addressing a real phenomenon here. Millennials (one of Oatly’s main target demographics) are saddled by debt and stagnant wages, and therefore less able to engage in material consumption. As a result, their tastes and preferences may be changing: for example, seventy-two percent of American millennials claim to favor experiences over possessions; nine in ten would switch over to a brand “with a cause”; and eighty-four percent of global millennials say they distrust traditional advertising.

In some ways, lifestyle advertising has attempted to get ahead of this change. Instead of selling products, lifestyle ads sell us aspirations, ideas, interests, and values. Gwyneth Paltrow’s lifestyle company, Goop, for example, isn’t just selling Psychic Vampire Repellent; it’s selling a healthy lifestyle as a whole––which naturally involves limiting vampiric influence.

Oatly, however, has done something markedly different from lifestyle advertising. Instead of reeling back its advertising in response to the rising tide of anti-consumerism, Oatly has doubled down, co-opting anti-consumerism into its very own branding. With a sprinkle of self-loathing here, a dash of existential dread there, and streams of quirky neuroses, Oatly’s ads have fully cashed in on the anxiety and disaffection millenials feel with late-stage capitalism. Here’s what it looks like:

I always wonder what combination of sycophancy and ignorance enables out-of-touch or just downright bizarre ads to advance through the bureaucracy of brainstorming, research, design, planning, testing, and execution. Think about it: a non-trivial number of suits and creatives at Oatly reviewed copy that said, “THIS IS THE ULTIMATE FOODIE AD FOR FOODIES WHO DON’T CARE THAT WE DON’T USE FOODIE PHOTOS TO SELL OUR FOODIE PRODUCTS” and thought, in unison, wow, what a zinger.

You might be inclined to think that Oatly’s ads don’t say much about American advertising, since the company has European origins. But consider the manner in which the American advertising community is frothing over Oatly’s campaign like it’s the next “Got Milk?” (“The Marketing Genius of Oatly”, “How Oatly Became the Brand to Beat”, “Oatly Used Many Strategies to Succeed in the U.S., but a Marketing Department Wasn’t One of Them”). Consider, also, how American brands like Hinge and RXBAR have taken to more “honest” forms of advertising in the last several years:

I can understand why people working for these brands might want to have a little fun under the soul-crushing weight of global capitalism. But there’s a problem with these brands posturing honesty through advertising, which is an inherently dishonest and coercive medium. As Chomsky explains in Making the Future: “The advertising industry’s prime task is to ensure that uninformed consumers make irrational choices, thus undermining market theories that are based on just the opposite.” Classical economic theory assumes that people are naturally “rational choice makers” who will buy things that align with their own personal needs. Ads, however, aim to enmesh the needs of consumers with the needs of business. They are trying to sell you what corporations need you to need.

Advertising has changed a lot throughout history, namely because of technological change. The radio and the TV, for instance, gave advertisers the power to intrude upon the domestic sphere, where they could better reach the eyes and ears of children.

The ad industry’s biggest transition, though, was not technological but psychological. In Business Enterprise in American History, Mansel Blackfield and Austin Kerr recount a transition which occurred roughly around the turn of the century:

“Before 1910, advertisers mostly sought to inform customers about products; after 1910, the main goal was to create a desire to purchase products. By the 1920s, advertising executives recognized that theirs was a business to make consumers want products, and they deliberately sought to break down popular attitudes of self-denial and to foster the idea of instant gratification through consumption”

Late 19th-century advertising appealed to the basic needs of the American people by being informative. But early 20th-century advertising, which helped fuel the Roaring Twenties, was about manufacturing desire with the power of persuasion. When Coca Cola was invented in the late 1880s, for example, it was marketed as a medicine that could cure headaches, addiction, and impotence. By the 1920s, Coke was instead branded as a “social lubricant” that was refreshing, delicious, and fun. By associating Coke with positive psychological feelings, like social connectedness, Coca Cola tricked people into believing its products were spiritually and emotionally fulfilling. And so ads became coercions designed to convince us that material things would satisfy unconscious desires.

In Oatly’s case, nobody has an unconscious desire to drink oat milk. But they might have a desire to be healthy, to reduce harm in the world, or to be a part of a community that values such things. Oatly’s ads––stripped-down with their black and white palette––might seem anything but coercive. Indeed, they appear “honest” and “authentic” because they omit a value proposition. Oatly’s ads go so far as to make fun of advertising itself, giving the impression that Oatly is not advertising because it wants to but because it has to.

But this of course is complete and utter nonsense. No business has to launch a global multimillion-dollar ad campaign hellbent on making sure you see the word “OAT” every time you blink. More than this, there is something deeply disingenuous about a brand that preaches the value of waste reduction and resource efficiency, only to launch a massively wasteful global ad campaign that then paradoxically ridicules consumerism. This mess of contradictions exists primarily because Oatly’s brand vision is misaligned with its model for growth.

For example, Oatly-the-brand claims to be deeply committed to sustainability. Oatly has even been known to periodically release “sustainability reports” (which are now so ubiquitous and meaningless that even BP Oil has joined in on the fun). But in Oatly’s most recent sustainability report from 2018, nowhere does it acknowledge the little-known but highly deleterious effects of print and digital advertising on the environment. In 2010, it was estimated that the U.K. ad industry, for example, produces two million tons of CO2 annually, “the equivalent of heating 364,000 U.K. homes for a year.” In the United States, billboard ads account for approximately 10,000 tons of non-biodegradable PVC fabric waste per year. In 2016, the global electrical output required for all online advertising produced an estimated 60 million tons of CO2e (CO2e represents all greenhouse gases––not just CO2). In other words, ads are not just mental pollutants––they are environmental ones too.

Of course, none of this is to say that Oatly’s ads are ineffective in their creative strategy. One study out of the University of Minnesota, found that ironic advertising may lead to “higher attention” and “greater involvement in the ad message.” As professor of psychology Tim Kasser puts it: “An ad that says: “‘Yes, I know you know that I’m an ad, and I know that you know that I’m annoying you’ is a statement of empathy, and thus a statement of connection. And as any salesperson will tell you, connection is key to the sales.” So, ads can connect with us, even if the basis of that connection is motivated purely by need for more profit.

For example, there may be something genuinely funny about a little green gecko selling you car insurance. Such ads humanize GEICO and let us believe that the insurance goliath understands us, shares our sense of humor, and dare I say, has our backs. But consider the fact that GEICO spent $2 billion in advertising last year. This means that GEICO spends in annual advertising roughly the same amount of revenue it makes in an entire fiscal quarter.

More surprising, while there is a positive correlation between GEICO’s ad budget and its customer uptake, the relationship isn’t necessarily causal. For example, Allstate spent roughly half the amount GEICO did in 2015, even though it took in only 1 percent fewer new customers. As Jessica McGregor and Megan Sutela explain in Insurance Journal: “It is not necessarily the amount of money spent on advertising that influences the new business yield rate, but other factors such as advertisement content, advertisement demographics targeted, word of mouth, and brand reputation.” This means that GEICO might quite literally just be blowing through cash to raise awareness of a brand everyone already knows, when it should be focusing on customer satisfaction, which translates of course to customer retention.

In the RAND Journal of Economics, Ulrich Doraszelski and Sarit Markovich say that in a competitive environment, “industry dynamics…resemble a rather brutal preemption race” where “firms advertise heavily as long as they are neck-and-neck.” Advertising amongst big competitors is a game of one-upmanship, where they’re all desperately attempting to get ahead of one another in order to capture a bigger market share. Meanwhile, “incumbents deter [market entry] by overadvertising.” Oatly is a company which has been in the alt-milk space for over twenty years and is arguably the foremost “incumbent” in oat milk. So there is no extent to which Oatly’s mass advertising can truly be a good-faith attempt to “connect” with customers on a “real” level; such behavior only serves the primary purpose of aggressively boxing out competitors.

A more socialist reality would likely dispense with advertising as it’s generally understood, let alone “honest” advertising. As Philip Hanson explains in Advertising & Socialism:

“Soviet writers on advertising stress that in a ‘socialist’ (i.e. Soviet-type) economy basic production decisions are centralised and marketing decisions are not left to those in a private-enterprise economy who have a material interest in selling more […] Central planning of the growth of private consumption can reflect people’s true wants rather than the particular interests of private sellers.”

This isn’t to say that the U.S. government needs to implement a “five-year-plan” and radically nationalize all milk brands. Rather, it should be subsidizing, taxing, and regulating the milk industry (including non-dairy milk) in the interest of the American public––not the interest of dairy producers. But of course, the federal government is doing no such thing. In fact, it’s providing the dairy industry with tens of billions of dollars in subsidies every year, when this same industry dumps around 3.7 million gallons of milk per day, contaminates soil and groundwater throughout the country, produces 3.4 percent of total national greenhouse gas emissions, and actively propagates pseudoscience to artificially inflate demand. And it’s doing this so the dairy industry can maximize profits at any cost.

However, a socialized version of the milk industry––one where true demand is met by supply through government intervention––would likely entail the death of dairy, which would pave the way for alternatives. This kind of market environment would probably obviate the need for modern advertising (since ads attempt to artificially influence market forces). And eventually, this unthinkably wasteful $1.2 trillion industry built around finding the next slick way to “connect with” or “tell a story” to consumers about, say, a “fearless” milk brand, would vanish. Not even feigned attempts at self-loathing would suffice.

While a company like Oatly is far from the worst offender in the grand scheme of capitalism, it is nonetheless important to be vigilant of the snakes in the grass, who give the impression that advertising can be innocuous or even empathetic. Such impressions ring hollow against the reality of capitalism’s monstrous appetite for profit––even in the case of “outsiders” like Oatly. After all, Oatly has in time shown itself to be anything but an outsider: It’s a company that accepts private equity money; it contradicts its own ethos of sustainability; and it uses aggressive marketing tactics to box out smaller competitors in service of an insatiable appetite for global expansion. So don’t be fooled. There is no “realness” to be found in their ads––just crude imitations with a slick new typeface.

.png?width=352&name=r-cohen%20(1).png)