What Does it Take to Be a Frasier

Why does lowbrow entertainment about highbrow culture speak to us? Aisling McCrea explores the snooty universe of Frasier.

It is common for people to point at a piece of abstract expressionism and say “My five year old could do that.” (So common, in fact, that art historian Susie Hodge wrote an apologetic for modern art called “Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That.”) The response by abstract expressionism’s defenders, especially when these conversations take place online or in print, is to insist that for many such works of art you need to be there to appreciate them. “Being there” can mean a kind of submission to the vibe: throwing away for a second your cynicism, allowing yourself to open a space in your mind and believe that there might be something to what is being presented. But it can also mean literally being in front of the work in person. Personally, I have found this helps clarify my relationship with some modern work labelled ‘high art’ and not with some others; I feel nothing when I look at splodges by Ellsworth Kelly, but am fascinated by the splodges of Thomas Downing. Most clichéd of all, I feel hypnotized when I look at the paintings of Rothko, an artist who profoundly affects many people but whose work is equally excoriated for being pretentious, childish, or a case of the emperor’s new clothes. I have no formal education in art criticism, and can’t speak on brushwork or texture or whatever. All I can tell you is looking at a Rothko always gives me a very specific feeling of looking out of a window, but every painting is a different window. Some of them are those weird high-up bathroom windows in bars late at night when you didn’t really feel like coming out, and some of them are hotel windows when you’re on the road and feel distinctly like you’re both nowhere and everywhere, and some of them are like looking through the window of an older relative’s house at Christmas. But I didn’t feel any of that until I saw them for myself. Apart from everything else, this may be one of the insurmountable obstacles of visual art, and part of why it has a reputation for pretentiousness: the first thing you are told about it, in response to any skepticism, is that you must pay god knows how many dollars to get to some major city with a high cost of living and walk through the squeaky-shoe hallways of a space that tells you you must appreciate this art. It will prove your sophistication. This is what grownups do.

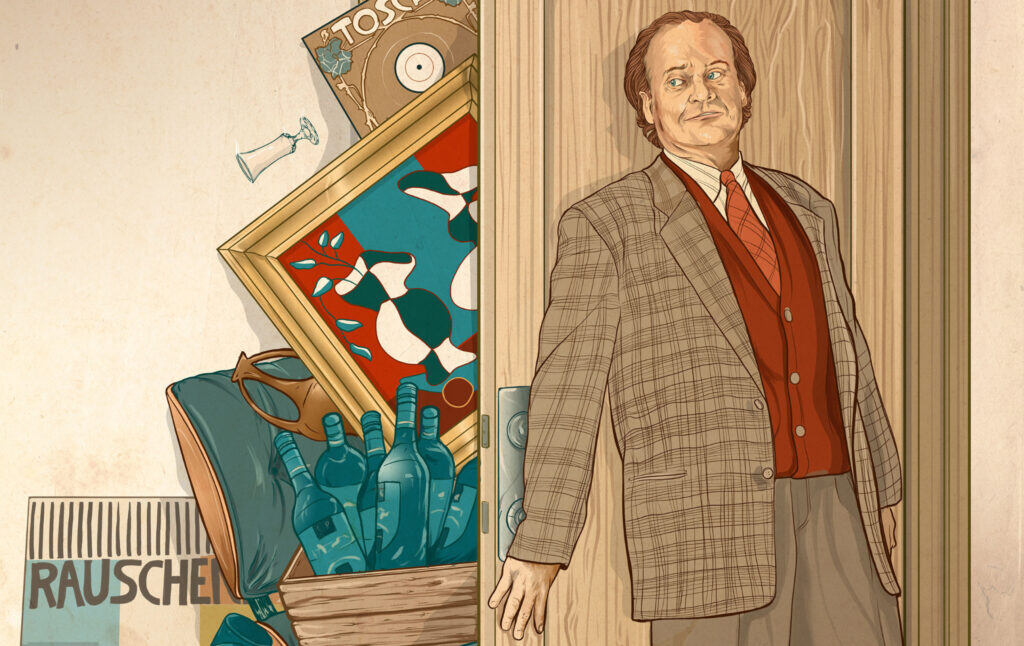

Frasier (1993-2004) is a sitcom about the life of the wealthy aesthete Dr. Frasier Crane, a spinoff of the Boston-based sitcom Cheers. While Cheers centered around the down-to-earth clientele of a friendly neighborhood bar—where the stuffy and overeducated Dr. Crane was an anomaly—Frasier follows the life of its titular character as he leaves Boston for his hometown of Seattle, takes up a job as a radio personality, and tries to inveigle his way into local circles of cultural power—its wine clubs, its lavish fundraisers, its high society dinner parties. Along the way he is both helped and hindered by his brother Niles, an even more obsessive social climber who has married into money, and clashes with his no-nonsense ex-cop father.

The first season, as in many sitcoms, has an unsteady mood as the writers try to figure out the exact tone they’re going for; the show starts out a little slow, and the brothers’ adventures in snootiness are sidelined in favor of exploring the father-son relationship. However, after that, the show finds its niche as a well-tuned farce with an air of sophistication: Frasier or some other character misunderstands something, other characters go off into a room and hatch some scheme, some absurd situation is set up and we get to see it all play out. One could imagine a similar show set amongst suburban housewives or fishermen in Alaska and it would still be great, but what makes Frasier memorable to a lot of people is the Crane brothers’ adventures in the absurd world of Seattle aristocracy: the soirées thrown by stone-faced heiresses, the barbs traded over antique furniture, and Frasier’s impossible apartment full of conversation pieces. (That’s “impossible” both geographically and financially: a recent GQ article by Gabriella Paiella calculated that even a well-heeled professional like Frasier would not have been able to afford the down payment on his three-bedroom condo with its view of the Space Needle, let alone the mortgage). Some of the best episodes feature Frasier and Niles plotting and bickering over some absurd status symbol, such as who gets to be part of an exclusive club, or who has the higher IQ.

In between all this, they demonstrate their affinity for all things “high culture,” unrestrained by faux humility or any fear of being labelled snobs; they dine almost exclusively at pricey French restaurants and openly sneer at beer drinkers and barbecue. In a way, this dates the show: the 21st century standards of “culturedness” demand eclecticism, and a profession of love not only for “high culture” but for things once considered mass-produced drivel. As Frasier was going off the air, TV was already morphing from the idiot box to the home of prestige entertainment. The poptimism movement of the 2000s announced that pop music was as worthy of respect as any other genre, and music bloggers whose tastes were usually limited to Jesus and Mary Chain B-sides suddenly added one or two Alicia Keys tracks to their “best-of” lists, as evidence they weren’t just grumpy old men who hated everything made after 1994. Food trucks became gourmet; everything low got elevated. In 2021, it would make very little sense for the Crane brothers to sneer at beer and barbecue, since that’s exactly what the hottest restaurant in Seattle would probably serve.

Frasier is therefore a time capsule for a kind of “culturedness” that seems massively out of reach for most people. This is exactly why the jokes work, since Frasier is not a show about “high culture” but a show for a mainstream audience about characters who like “high culture.” When Niles says he would go to a desert island with “the coulibiac of salmon at Guy Savoy, “Vissi d’Arte” from Tosca, and the Côtes du Rhône Châteauneuf-du-Pape ’47,” the joke is not that the audience has some intimate shared knowledge of these items, it is that these items sound very pompous and obscure. (A pompousness and obscurity that gets doubled down on when Frasier responds “…you are SO predictable.”) The world of Frasier is thus a world of signifiers, where real artworks that have been venerated for decades if not hundreds of years amount to little more than a stand-in for “stuff a fancy guy would like which we assume you haven’t seen.” This does not augur well for what our society does with the art it considers its finest, and who exactly is allowed to view it.

Part of the inaccessibility of this fanciness stems from its expense. The Crane brothers’ lives are full of events: in the episode Dinner Party, they have to search through their calendars for weeks to find an evening where they’re both free, and all those theater outings must surely add up. Their homes are full of furniture and objets d’art which they can examine at their own leisure, rather than taking the day off work to travel to a museum (not that they appear to work much anyway). Their preferred footwear is a certain kind of shoe made by an Italian craftsman who can only toil over one pair at a time (when he completes them, “they ring the cathedral bells and the whole town celebrates.”) And they are exposed to new knowledge and experiences through their social connections, which cost enormous amounts of money to maintain.

My point here is not “this sitcom is unrealistic about finances”—I mean, jokes about the Friends apartment are as old as Friends itself—but that “culturedness” in Frasier is tied to a certain lifestyle. This is made explicit through an arc in the fifth and sixth seasons, when Niles divorces his wealthy wife and is briefly thrown into poverty (and by poverty, I mean “is forced to live on his therapist salary.”) This change in circumstances ejects him not only from his social circles but from his interests as well: without money, he loses both his access to the world of fine art and the status it confers upon him. The episode How To Bury A Millionaire shows him truly heartbroken and lost, as he resorts to playing ping-pong with his neighbors at his cheap and tacky new residence. Even his things don’t seem to join him in his new place; the things belong not to him, but to the other world, in which he cannot afford to remain.

It’s obvious that pretty much everyone has the ability to appreciate some kind of art. Most people have at least a few songs or movies that they love. But our relationship to certain kinds of art is more alienated and uncertain, and it is exactly this that Frasier plays on. Compared to popular music, which is pumped through our society everywhere from department stores to clubs to hospital waiting areas, and which becomes a shibboleth and a shared passion from a young age, we are taught that certain kinds of art are something apart from everyday life; something a few people know about, if they have the resources and interest to pursue it, but not something everyone wants or needs to know about, and which can only be truly explored through occasional visits to its hallowed shrines. Almost anyone can listen to the greatest pop music of all time right now if they want, but the work of the greatest painters is scattered across the world’s cities—often cities that are expensive to travel to or live in, even if the gallery itself is free—or cloistered in private collections. You can look at copies, of course, but is it the same thing to squint at Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa in a coffee-table book as it is to see all three hundred and seventy five square feet of it in the Louvre? We can read about why it’s important, we can see from a copy that it’s competently executed, we can even go on a “virtual tour” on the museum’s website, but are we granted access to its true beauty unless we pay for a trip to Paris?

And even when we go to galleries, our experience is mediated by the fact we are in public, not private. We can’t dance in the art gallery, the way we might dance our ass off in our homes with our headphones on when nobody’s around. (Well, you can if you don’t mind getting told off by the docent, I suppose, but most people do mind, and can’t.) We are conscious of the people around us, the bossy silence, the rules—no flash photography, no eating, no touching. We are encouraged to have a respectful relationship with the art, the way you have a respectful relationship with your old-fashioned father-in-law, keeping always at arm’s length. This doesn’t prevent us from occasionally having a moment with art, and sometimes art can be just fun—the figures of Reubens and Goya feel like they’re punching their way out of the canvas, and Kuniyoshi has some excellent woodblock prints of frogs fighting each other. Nonetheless, most people struggle to get close to visual art—especially contemporary art, which frequently resists obvious displays of skill and is shrouded in its complex relationship to its reputation—and any other artform which society tells us there is a “correct” way to appreciate.

The philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin wrote about this contrast between art that requires presence and art that is accessible to all in his most famous essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. One of Benjamin’s insights is that forms of art resistant to mass production (e.g. paintings, handmade Italian shoes) have qualities that easily reproduced art (e.g. a music album) can never have. In particular, it has authenticity, the status conferred by the knowledge that it really is the original version of something which we hold in high regard, and it also has aura, that irreplaceable feeling we get from being in its presence. Aura is what I feel in front of a Rothko. Authenticity is what people feel when they see the Mona Lisa at the Louvre after seeing it hundreds of times in other formats (though interestingly many struggle to feel its aura these days, as they must view it through bulletproof glass and the heads of dozens of fellow gawkers). There’s an element of social construction to these qualities: if you’d somehow never heard of the Mona Lisa, would you be able to pick it out from a gallery of hundreds as the most important painting in the bunch? And galleries must surely add to the construction of aura, with their churchlike atmospheres. This makes it difficult, at times, to tell whether art has some intrinsic power, or whether the power we feel is a result of the status society’s gatekeepers bestow on certain works.

The Marxist art critic John Berger, in his beloved TV series Ways of Seeing (1972), essentially repeated Benjamin’s view, explaining how overexposure to copies of old paintings warps our ability to see them as they were supposed to be seen. But he also demystifies them, treating them not as magical creations existing purely for art’s sake but as products of their time, often grounded in their material, almost banal context—usually the context of a bunch of rich people who wanted to show off. As an example, Berger takes a much-romanticized landscape by Gainsborough and characterizes it not as a study of nature, but a boast by the aristocratic couple who commissioned and sat for it, a Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, who see the beauty of their land as a representation of their importance; just another aesthetic object that they own. This obviously doesn’t mean old art is bad. But it complicates the picture to add in the socio-economic context: that the valorization of beautiful things, things that can be transfixing, even transformative to many people, has always been tied up with status and possession—and possession necessitates exclusion.

As with any other show in the age of tabbed browsing, it is tempting to pause Frasier mid-episode so you can Google references you don’t get. In the case of most sitcoms, this means looking up obscure celebrities from the 1970s who were probably a big deal when the writers were young. In Frasier’s case, this means reading the plot of La Traviata and maybe watching a bit from Youtube. You don’t have to do this, but you might convince yourself it’s a way of getting cultural vegetables into your diet. (I hear what you’re saying, bellowing to me from your Eames chair: “Aisling, this is preposterous. Frasier is a comedy show, not a lecture series.” Well, is Frasier a stupid way of understanding “high culture”? Yes. Is there a less stupid way? Arguably no. The arts world is full of arbitrariness and gatekeeping. You may as well get your knowledge from a TV series with a funny dog in it.) All the while, as you squint at a low-quality video of an orchestra pit, you might quietly think to yourself: is there something I’m not getting? Is it wrong to be bored? Would it feel different if I were there? But even if you see La Traviata in person, the questions might continue. Am I enjoying this the right amount? Is there a book I should have read? If I knew more about the context, would I like it more? Is everyone just pretending? Or is it fine just not to like it? “High culture” by definition is always weighed down by these mille-feuille layers of questions: whether such-and-such work is part of the “canon,” if its place is deserving, which translation is best, which version is best, whether one must see it live, whether one must read the notes, whether one must stand on one’s head and watch the whole thing upside-down for the true experience to be granted by the arts gods. Sometimes our appreciation for a piece of canonized work can be instinctive and delightful, and often we’re actually surprised. Perhaps this is an indictment of what the canon actually does to our relationships with art: it’s not wrong for art to require effort to understand, but I’m not sure it should feel like so much work.

Frasier is a wonderful show. But it’s also a document of the wall between the finest things our world produces—or rather, what centuries of wealthy people proffer as the finest things our world produces—and the vast majority of people. The Crane brothers’ love of art appears to be genuine, although it’s a love mediated by ego and classism. Even when their snooty friends are not around they sing and play piano, they strive to perfect their cordon bleu cooking, and they rhapsodize about turquoise inlay, giving their lives a richness that appears to bless them at times with pure happiness. Yet this happiness is facilitated by a ludicrous, never-ending pile of wealth, and the rigorous social training bestowed on them by decades of elite education and assiduous schmoozing. Most people’s relationship with art is not quite so blessed. Financial and geographical hurdles, class relations, insecurities and social guessing games all work to turn culture into an ego trip for the rich and a minefield for everyone else. In Frasier, works of art become a joke, presumably not because the writers hate art, but because the art serves to show how unrelatable the Crane brothers can be. But wouldn’t it be nice if we lived in a world that took art seriously? And wouldn’t that entail everyone having access to art?