Those Who Rise and Those Who Disappear

Novelist Elena Ferrante’s real message is that class and power are the “sickness” of the world…

Imagine a place where work and income are insecure; where wealthy businessmen/criminals collude with police and politicians to exploit and abuse workers; where family relationships deteriorate into violence and anger under the pressure of economic hardship; where education is a commodity few can afford; and where, in the face of this hopelessness and powerlessness, the most vulnerable communities and individuals are eaten away by drug epidemics. Imagine, if you can, such a place.

This place—at least for our immediate purposes—is a poor neighborhood in post-World War II Naples, the setting of Elena Ferrante’s blisteringly brilliant and critically acclaimed Neapolitan Novels. The four books follow the lives of two women from childhood into their sixties, from the 1950s to the 2010s.

One is Elena Greco, who gets educated and gets out, and writes the story of her life, the books we are reading. Hers is the traditional bildungsroman, a Dickensian tale of miraculously surviving a senselessly cruel childhood to find success, order, comfort, benevolence, and recognition in the great wide world.

The other is Lila Cerullo, Elena’s best friend, obsession, and photo-negative. As children, they bond over their shared intelligence and curiosity, but their lives diverge. As Elena gets to leave the neighborhood, Lila stays. Where Elena seeks to please, Lila fights to assert herself. Where Elena advances into the educated classes, Lila rails against the power systems that hem in her life and is knocked back at every turn. Where Elena publishes books and makes a mark on her world, the more gifted Lila figuratively and literally disappears.

Our imaginations are awash in stories like Elena’s: a hundred-billion-dollar company that started in a garage; an unemployed single mother who wrote on a manual typewriter a book-turned-film-franchise-turned- theme park at Universal Orlando; a poverty-stricken, abused child who became a media mogul. We need these stories; we use them to justify a lot of misery.

But we’re not very good at the Other Stories: the ideas that never left the garage, the single mothers whose books never sold, the survivors of abuse who don’t go on to rule daytime TV. The artistic and political genius of the Neapolitan Novels is the recognition, in Lila specifically, of these many, many Other Stories. Or, more accurately, the genius of these novels is the demonstration that the Other Stories are not—and maybe, under present circumstances, cannot be—told.

The Ferrante series is a searing criticism of power, inequality, and the class system. It has sold over 10 million copies, according to Wikipedia, and the first book has been developed into a series on HBO (and they’re working on season two!). The books speak to the anxieties and inane cruelties of living under a system in which some people enjoy security, education, safety, beauty, leisure, self-realization, and dignity, and the rest do not, and the line between these groups is drawn in a way no person of reason and good conscience can justify. The Neopolitan Novels are a cautionary tale, a catharsis, a call to arms, especially in the historically lopsided U.S. where wealth inequality has sharply worsened in recent decades, and where the ruling class has shown itself uninterested in addressing this situation as a problem.

Certainly our culture-makers—the thinkers and creatives at the helm of our collective imagination in this desperate political moment—jumped at the chance to praise these books’ ability to speak directly to the deepest fissures among us.

Of course I joke.

The reviews of this series—and there were many—talked about female friendship, about feminism, about working and succeeding as a writer. None of these descriptions is wrong, exactly, but they miss the full force of the story and sap it of its strongest claims and critiques. The reviews did not discuss the class designations that rule and constrain the characters, and determine every outcome of their lives. They did not examine the systematic erasure of Lila or dissect Elena as an unreliable (really, failed) narrator of her own story. They seemed to miss the central tension in the relationship between these characters. Puzzlingly, reviewers discussed the books as a classic rags-to-riches tale but with ladies: Elena was the protagonist and Lila was seen as inconsequential, or a burden, or an obstacle, or a villain.

This interpretation is wrong, but it’s wrong in an instructive way, in a way that shines light on how sharp this story really is about the limitations of art in a world carved up by inequality.

(I thought often of Elena’s shortcomings as a storyteller—and the tone-deaf reviews of these books—in the wake of the 2016 election, when these same newspapers and magazines looked to J.D. Vance, the Elena Greco of Appalachia, to explain “what happened” with rural voters in the United States. A better reading of these novels could have saved everyone some time, and it could have saved anyone from feeling compelled to read J.D. Vance.)

That these reviewers empathized with Elena’s plight to the exclusion of Lila’s is not a surprising move: by now we are used to mainstream publications being written for, by, and about Elenas and generally reacting to the world’s Lilas with perplexity, disinterest, disgust, pity, or outright hostility. (The novels themselves tell us this: the rich and powerful are a group of people who, Elena observes as a teen visiting the posh part of town, “look only at each other.”)

But this reading of the novels—the praise of Elena and the vilification of Lila—is lazy and wrong, and I think we should take issue when the class provided the time and platform to read and interpret can’t even do that properly. (The novels, masterpieces that they are, warn us about that, too.)

The narrative force of the story is Elena’s stated resolution to understand Lila, to prevent her friend from disappearing by writing about her, and Lila’s supposed insistence on remaining elusive (Lila has, in fact, forbidden Elena from writing about her, for reasons that are not explained but can be guessed at). This is the drama that kicks off the narrative in Book I: Lila has disappeared and Elena will write her down. Here is Elena after learning in a phone call about Lila’s disappearance:

She wanted not only to disappear herself, now, at the age of sixty-six, but also to eliminate the entire life that she had left behind.

I was really angry.

We’ll see who wins this time, I said to myself. I turned on the computer and began to write–all the details of our story, everything that still remained in my memory.

And here is the near-end of Book IV, the end of the novel the character Elena is writing:

It’s only and always the two of us who are involved: she who wants me to give what her nature and circumstances keep her from giving, I who can’t give what she demands; she who gets angry at my inadequacy and out of spite wants to reduce me to nothing, as she has done with herself, I who have written for months and months and months to give her a form whose boundaries won’t dissolve, and defeat her, and calm her, and so in turn calm myself.

(There are five more pages, the end of the Neopolitan Novels, that contain a stomach-churning twist which should definitively cast doubt on Elena’s ability and intentions as a writer; I wonder if maybe these pages were left out of the reviewers’ copies completely.)

Many reviewers took the fictional Elena at her word, that she was simply trying to understand her friend and that, in the end, the writing of her novel and Elena’s own professional successes redeem the tragedy of Lila’s fate. Sure, Lila’s genius is trampled to inconsequentiality by a harsh life. Sure, Lila’s efforts to grow her family’s shoe business are co-opted by the local Camorra crime syndicate, whom Lila hates. Sure, her daughter is killed or kidnapped as a young child, her brother dies of a drug overdose, and her son becomes an addict. Sure, Lila is cast aside or ignored by their grade-school teacher (she is a “pleb” whom Elena should avoid), by her bosses, by her doctors, by Elena herself. Sure, Lila literally disappears without a trace.

But don’t worry, these reviewers comfort us, Elena won’t let Lila be forgotten. Because Elena has written a book about her.

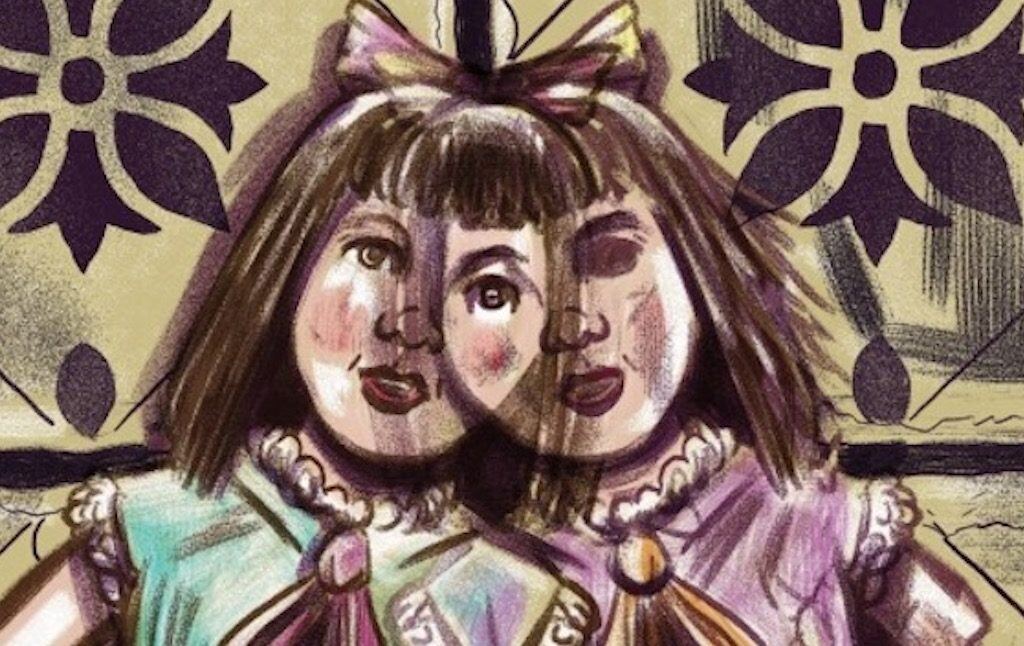

Illustration by Mike Freiheit

Here is the New York Times’ take on Elena in its review of the final novel:

Elena lives on to make her plodding progress from vulnerability to education to self-realization. She becomes, in short, normal — and this, Ferrante suggests, is where the female drive toward autonomy, with all its racking, successive waves, will ultimately deliver us: into a reality that is, if not transformed, at least better adjusted. Elena and Lila may both suspect that Lila possesses the greater, more radical brilliance. But the achievement of these novels belongs solely to Elena.

Why would we want “radical brilliance” when we can simply be “better adjusted” to the injustices of the world, to the decimation of our friends and communities?

The New York Review of Books echoed this contrast: Elena is the subject, the actor, and doer, and Lila serves as little more than her “inspiration”:

Elena has the discipline to channel her gifts, as she shows in the writing of her story. But she could not have done so without the inspiration of Lila, who is the more brilliant but too mercurial to fulfill her promise, whether as an author (the story she wrote as a child, The Blue Fairy, mesmerizes Elena), shoe designer, or entrepreneur.

This reviewer’s explanation of Lila’s creative and business failures is…interesting. Lila is “mercurial.” Forget that Lila was a ten-year-old child reliant on her father to pay for schooling he couldn’t afford and didn’t value for her, a father who responded to her relentless requests to attend middle school by throwing her through their apartment window; forget that Lila returned from her honeymoon so bruised from beatings (related to her arguments with her husband about his handling of her family’s shoe business) that she was too ashamed to be seen by Elena; forget that Lila is later brutalized as a worker in a sausage factory, forget that her romantic and business partner is wrongfully imprisoned, forget about the drugs, forget about the kidnapping of her child. Forget about Lila’s lack of access, her lack of options, her material vulnerability even as she fights for dignity and autonomy. Forget that every expression of her dazzling brilliance has been met at best by indifference and at worst by outright violence. Lila’s just got a bad case of the “mercurials”!

The New Yorker followed suit, casting Elena’s artistic effort as an admirable expression of the suffering, disenfranchisement, and collapse of Lila and the rest of their community:

To Lila’s oppressive disorder…[Elena] will oppose her own, once-despised instinct for order. Dispersal will meet containment; dialect, Italian. This is an old literary trick, or at least as old as Proust: to tell a story of pain and defeat and then, at the end, say that it will all be redeemed by art, by a book—indeed, the book you are reading. Lena will write for months and months, for as long as it takes, she says, to give Lila “a form whose boundaries won’t dissolve.” She will thus calm her friend, and herself—and, to reach beneath the metaphor, rescue life from grief, clarity from chaos, without denying the existence of grief and chaos. She pulls her chair up to her desk. “We’ll see who wins this time,” she says. Art wins. We win.

Who is the “we” here? The New Yorker can admit—and does not seem bothered by—the fact that the winning “we” does not include Lila. (In fact, I would argue that no one “wins,” least of all we as readers and Elena as a writer.) It is troubling that this reviewer sees Elena as a success, and it is troubling that she shares Elena’s resentment against Lila, who has done little more than suffer and fail the entire length of four novels.

Lila’s disposability is again articulated in an Atlantic review in which the reviewer describes Lila cutting herself out of her family pictures, one of her attempts to make herself disappear. “But Lila’s ambition backfires—she’s more present in those butchered snapshots with their glaring voids than she was in photographic form.” Again, the reviewer does not seem bothered by the fact that the most accurate and poetic representation of Lila is absence. Nor does the reviewer consider that Lila herself may be exercising some artistic agency in this act.

In these reviews, Lila’s unrelenting suffering is not taken seriously in part because Lila is not seen as a real person. The Slate reviewer states this unequivocally:

In truth, Lila is a character so extreme, so unadulterated in all her qualities—fierceness, courage, defiance, honesty, resourcefulness, determination, self-reliance, and, eventually, pessimism—that she never seems persuasively real. Actual human beings relent every now and then. They doubt. Instead, Lila is a personification, the distillation of everything admirable, if also often harsh, in the neighborhood that Elena has tried to leave.

In this reviewer’s world, bright, creative people like Lila who survive in poverty and aspire to a better world simply cannot be real. There are no people who suffer and fight as Lila suffers and fights. I will grant that the version of Lila we get through Elena’s eyes is purposefully incomplete. We don’t know how Lila relents, we don’t know Lila’s doubts, because we never intimately know Lila’s point of view. This is key.

But how do you read about this captivating woman battling for her existence around the edges of Elena’s life and not want to know more about her, to hear her story from her directly? To say Lila does not seem real betrays a lack of empathy that feels insurmountable. Lila embodies the forgotten, the misunderstood, the lost, the losers of what feels like a social and economic lottery. Under global capitalism in the 20th and 21st centuries, that is a lot of people. The blindness of these reviewers to Lila matches the political blindnesses of the class of people who benefit from these structures.

But this is not just about bad politics; it’s bad reading interpretation, too. There is ample evidence in the novels, even barring the ending, that Elena is not to be trusted as a narrator. She herself tells us; she tells us what she doesn’t understand about her friend, about her neighborhood, about the very subjects of her books.

For instance, she tells us she is uninterested in politics and the material conflicts of the neighborhood. As an adult, Elena returns to live in Naples for creative inspiration, and she resents Lila’s efforts to interest her in their provincial concerns:

[Lila] didn’t care in the least about freedom of expression and the battle between backwardness and modernization. She was interested only in the sad local disputes. She wanted me, here, now, to contribute to the clash with real people, people we had known since childhood…”

Elena cannot muster up the interest. “[B]ecause of [Elena’s] respectable identity,” she has “lost…the capacity to understand.” Elena addresses herself:

…you’re too well-meaning, you want to play the democratic lady who mixes with the working class, you like to say to the newspapers: I live where I was born, I don’t want to lose touch with my reality; but you’re ridiculous, you lost touch long ago, you faint at the stink of filth, of vomit, of blood.

The turmoil in Elena about her limitations in understanding her origins is important but unaddressed in these reviews: why can’t Elena as an adult understand the place where she grew up and where she currently lives? Why does she remain stubbornly ignorant about the political realities of this world and, by extension, about her oldest and closest friend? This is not the good-faith effort of a writer or a person trying to capture Lila and their shared community.

Even when Elena’s willful blindness was acknowledged by the reviewers, it was to unsatisfying ends. The Guardian grapples with Elena’s decision to throw her friend’s childhood journals into the river at the beginning of Book II. Lila, worried her new husband will read them, entrusts the journals to Elena; Elena pores over them and, feeling “exasperated,” disliking “feeling Lila on me and in me,” drops the journals into the river. The Guardian review rationalizes this callous act: while Elena “minds her language, Lila says what she likes, but nothing that can be published. That’s why Elena throws Lila’s notes away: though hope remains in the box, what Lila had to say must have been unbearable.” The underlying premise that we should not be writing or reading things that are “unbearable” goes unexamined, along with the contradiction between Elena’s stated purpose—keeping her friend from disappearing—and her actions—tossing her friend’s journals into a river. This level of cognitive dissonance takes a lot of practice.

The logic of these reviews is trapped in a worldview in which Elena the self-realized class-climber deserves to exist, while Lila—because she is too radically brilliant, because she describes a reality that is unbearable and disordered, because she is too “mercurial”—does not. Materially, the great difference in Elena’s and Lila’s lives is that, when they are ten and their teacher recommends they both continue their schooling, only Elena’s family pays for her to attend middle school and beyond. Lila’s does not. Everything else flows from this: Elena plods steadily up the economic and social ladder, taking on the language, behavior, and values of the elite to join their class; Lila drifts in ways bewildering to Elena, carried by waves of poverty, abuse, and what Elena perceives as self-destruction.

In the end, based on this accident of access to formal education, Elena matters and Lila does not. In the end we have “their” story, in Elena’s words, from Elena’s perspective, in Elena’s novel. We are meant to be disturbed by this outcome; we are meant to be unsatisfied by Elena’s pat explanation of her rags-to-riches life. Elena’s story is captivating, but the great question of Lila remains unanswered.

But still—still—this chorus of reviews is unable to see beyond Elena.

To understand how truly bad and wrong this interpretation is—that Elena has imposed order on disorder, has rescued “clarity from chaos”—we will analyze the ending. (Ferrante’s talents as a novelist cannot be overstated. She cares about being entertaining, she cares about plot and twists and dramatic reveals, she cares about keeping her readers flipping pages. The Neapolitan Novels have good politics, but before that they are just really, really, really good books.) While Elena Greco’s novel may end with a tidy button, Elena Ferrante’s novel ends in turmoil.

To explain the gut-punch of the ending, I have to explain the significance of Elena’s and Lila’s dolls.

Some of Elena and Lila’s first bonding experiences came from playing with their dolls, Tina and Nu, respectively. One day, they exchange dolls, and Lila purposely drops Tina through the grating over a basement window. (Elena describes this as a time period during which Lila “began to subject [her] to proofs of courage that had nothing to do with school.” To Lila, this time period was…well, we don’t know.) Elena drops Lila’s doll in response (“What you do I do”) and they go together to the basement to retrieve the dolls. The dolls are not there, and Lila convinces Elena that she has seen Don Achille, the loan shark, the neighborhood villain of their childhood, steal their dolls.

This memory is temporally tangled with the revelation that Elena would be attending middle school and Lila would not. As Lila continues to bargain with her family to continue her education, she decides that she and Elena will confront Don Achille and demand the return of their dolls. After some confusion and disbelief at the accusation, Don Achille gives them money to buy new dolls and to remember that the new dolls are a gift from him. Elena thanks him; Lila does not. (Ferrante truly does not miss a beat; Elena the social climber is characteristically eager to please people in positions of authority. Lila, for good reason, is suspicious of and combative with these people, even at a young age.)

Elena and Lila instead use the money to buy a copy of Little Women, a book that stirs their imaginations and inspires their dreams about writing books and getting rich. (Incidentally, this is what Elena ends up doing.)

The subject of the dolls resurfaces periodically in their relationship. Lila marries Stefano, the son of Don Achille, full of conviction that her new husband will use his money and power to improve the neighborhood, abandoning the violent and cruel ways of his father and their childhood. After that dream is shattered and Lila shares with Elena their violent fighting, Lila reflects on their childhood confrontation of Don Achille and expresses regret for taking the money, feeling tricked by both Stefano and his father: “‘…ever since that moment I’ve been wrong about everything.’” There is no further explanation.

Elena brings up the dolls again when they are pregnant with their youngest children at the same time:

Do you remember, I asked. She seemed bewildered, she had the faint smile of someone struggling to recapture a memory. Then, when I whispered to her, with a laugh, how fearful we were, how bold, climbing up to the door of the terrible Don Achille Carracci, the father of her future husband, and accusing him of the theft of our dolls, she began to find it funny, we laughed like idiots…

Again, we have no further explanation of Lila’s reaction.

The next reference comes at the very end of the series, those final five pages that occur after Elena Greco has completed her novel. Elena spends the morning playing with her dog and reading the newspaper, and then she returns to find in her mailbox a package wrapped in newspaper. It contains the lost dolls from her childhood.

But no Lila.

Elena, as usual, tries to divine Lila’s meaning. She accuses Lila of deception, of dragging Elena through a story over which Lila had the ultimate power all along. Or maybe the dolls are a sign of love, that Lila is traveling the world and enjoying life. The point, again, is that Elena will never know, and neither will we. She looks at the dolls: “Seeing how cheap and ugly they were I felt confused. Unlike stories, real life, when it has passed, inclines toward obscurity, not clarity. I thought: now that Lila has let herself be seen so plainly, I must resign myself to not seeing her anymore.”

So: Lila has had these dolls for fifty years. Elena and Lila bond over the dolls as children, the dolls’ disappearance plays a critical role in Elena’s path to becoming a professional writer, and Elena and Lila discuss the dolls’ disappearance at significant moments in their lives. And Lila has had these dolls this whole fucking time. Why? Why does she take them to begin with? Why does she hide them from Elena? Why doesn’t she tell Elena about them? Why does she compel Elena to confront Don Achille about them? Why does she finally leave them with Elena in the end? What does Lila mean when she says she’s been wrong about everything since the dolls? Is she wrong then or is she wrong now, and about what? What is Lila’s purpose?

Elena doesn’t know. This is how the series ends: not with the triumph of Elena’s art but with its failure. Not with order and clarity but with Elena and the reader scrambling after Lila for answers. The loss is tragic, and we feel it acutely at this unresolved ending. The triumph here is absolutely not Elena’s, who cannot understand her friend, who cannot understand the story of her own life. If anything, the triumph of these novels belongs to Lila, who was able to poke through this medium that was not constructed for her, this book she was not able to write and publish herself, to communicate the harrowing story of her disappearance.

The triumph also belongs to Ferrante. Art in general and novels in particular are as co-opted as anything by global capitalism and its class system: books generally are written for, by, and about Elenas. And yet the Neopolitan Novels, at their critical moment, turn the attention entirely to the Other Story, the story that was not told.

I closed the back cover of the last installment and my first thought was: I wonder if Ferrante will write this story from Lila’s perspective.

Followed immediately by: oh, no, she won’t.

And then: oh, no. She can’t.

That’s the whole point. Although Elena (and maybe Ferrante herself) shares a background with Lila, to find stability and success Elena takes on the language, behavior, and values of the elite; from this position of power, Elena tries to understand her friend, their relationship, and by extension her own story. She fails. For arbitrary and ordinary reasons, Lila (like nearly every other person from their neighborhood, like most people everywhere) does not become a part of this elite. She struggles on the margins of Elena’s life, and then she disappears entirely. (The other people from Elena’s childhood disappear in their own ways: prison, drugs, death.) This is the tragedy of these novels, of class division: the loss of the vast majority of people, the loss of unknown and untold talents like Lila’s, and the resulting ignorance of the powerful few whose construction of reality we are all beholden to.

I think this book should be taught in schools, though not as it was reviewed by these media outlets. I think it should be passed around leftist book clubs. I’m glad that it’s risen to such popularity as a story about “female friendship” (almost like actual friendship!) but don’t let this billing obscure its real message: that class and power are the “sickness” of the world.

Get away for good, far from the life we’ve lived since birth. Settle in well-organized lands where everything really is possible. I had fled, in fact. Only to discover, in the decades to come, that I had been wrong, that it was a chain with larger and larger links: the neighborhood was connected to the city, the city to Italy, Italy to Europe, Europe to the whole planet. And this is how I see it today: it’s not the neighborhood that’s sick, it’s not Naples, it’s the entire earth, it’s the universe, or universes. And shrewdness means hiding and hiding from oneself the true state of things.

The world is made up of a few Elenas who look only at each other to hide from themselves the “true state of things” and many, many more Lilas at various stages of disappearance. In this reality, in the reality of class division and inequality, the world continues to be “sick,” the powerless continue to disappear, and the powerful can do nothing more than scratch their heads and, like Elena, fail to understand why.

This article was originally published in the January – February issue of Current Affairs.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.

.png?width=352&name=r-cohen%20(1).png)