How “Creative Jobs” Pervert Your Soul

The marketing industry and its discontents…

Creative jobs sound nice, especially if you’re currently stuck in an uncreative one that you don’t particularly like. Instead of emptying portable toilets or placating Under Armor-clad suburban tyrants who holler for your manager whenever you run out of decaf, you could be living in a glamorous Mad Men-ian world of brilliant colleagues, gorgeous workspaces, and long boozy lunches. Creative jobs sound attainable, too. Maybe you couldn’t be Steven Spielberg or Shonda Rhimes, but you could definitely be the person who writes their tweets. The pay would be good, and the work would be satisfying.

It sounds like a dream, but a very reasonable dream, because creative jobs are still jobs, and like any job they would have their downsides. The hours would probably be long. There would be lots of meetings, many of which would be boring, pointless, or both boring and pointless. Sometimes the clients would be lunatics. But even the bad parts about a creative job can be justified with ease, because they help soothe the suspicions of parents and peers when you say, “Yeah, I make memes for a living, but I’m doing it for brands. We don’t have a ‘real office’, no. However, we do have a thriving and vibrant Slack.” Creative jobs offer the best of both worlds: You get to feel like an artist, but get paid like someone whose work is actually valued.

This is the conventional view of creative jobs, and I would like to suggest that it’s utter horseshit.

Someone is thinking about you right now. They’re trying to imagine what you’re wearing, what you’re eating, what you’re texting your sister. They want to know if you believe in God and if you have any recently deceased pets. They’re desperate to discover what makes you horny. Anxious. Mad. They study your tweets and Facebook posts like Jane Goodall studies chimps, trying to understand what’s going on inside that mysterious head of yours. They know about the half-eaten Chinese takeout in your fridge and the vibrator in your sock drawer. They watch you when you go the beach, they follow you when you go to the zoo, they stroll with you down the aisles of the liquor store, keeping meticulous notes about every person you greet along the way. They know where you went to elementary school, they know how often you visit the doctor. They have spreadsheets full of your favorite websites, your least-favorite films, your most flattering selfies.

And yet no matter how much they learn about you, they’re still hungry for more. They can’t stop thinking about you. They spend their days dreaming what it’s like to be you. You might call them creepy, obsessive, even criminal. Or you might just call them marketers, the single most grotesque embodiment of all that is contemptible about “creative jobs.”

They’ll get quite upset if you say that, of course. Not the part about being a marketer (they’re proud of that), but the part about having dubious intentions. “You’re misunderstanding me!” complains the marketer. They mean you no harm, they just want to educate you. They’re trying to make you happy. They only want to be loved by you.

“This is insane,” you might say. “You don’t give a single solitary shit about my well-being, you’re just stalking me so you can manipulate my behavior for profit. What the hell is wrong with you? Go away! No, I wouldn’t like to take a quick survey about my experience!”

The marketer will protest, claiming to have nothing but the greatest respect for you, the beloved consumer. “Marketing isn’t stalking,” they’ll say with an indignant squeal. “Marketing is storytelling!” It’s a creative endeavor, an art, and there’s nothing wrong with pushing its boundaries. Plus, it’s just their job.

They really believe this, too. Maybe marketers aren’t always angels, but their hearts are in the right place. One of the most famous marketers alive, Seth Godin, once wrote:

The truth is elusive. No one knows the whole truth about anything. We certainly don’t know the truth about the things we buy and recommend and use. What we do know (and what we talk about) is our story. Our story about why use [sic], recommend or are loyal to you and your products. Our story about the origin and the impact and the utility of what we buy.

This paragraph is magnificent, stirring, inscrutable bollocks. Here’s what it means in practice: Imagine you’re trying to sell herbal tea. Luiza herbal tea from Elon Moreh, to be exact. You’re a creative person, a storyteller. So you invent a story. It’s a calming and pleasant one—this herbal tea is special, it was made from the finest sun-kissed tea leaves, which were handpicked by family farmers who’ve worked the land for generations. Each cup is a moment of joy to be sipped in blissful tranquility as you curl up on the sofa with a soothing jazz record and the pitter-patter of raindrops against the window and a good thick book in your lap. Escape the hectic chaos of your daily life! Nurture your soul with a delicious cup of Luiza herbal tea from Elon Moreh!

Now, if you’d searched the internet for literally 10 seconds, you would’ve found some facts that complicate your story. You’d discover that Elon Moreh is an illegal Israeli settlement built on land that was stolen from Palestinian villagers, and that its “family farmers” are, in fact, M16-toting messianic zealots who set their neighbors’ olive trees ablaze for fun and harass children who are trying to walk to school. You’d realize that hundreds of Palestinian mothers and fathers have been beaten, starved, threatened, blackmailed, humiliated, imprisoned, tortured, raped, or killed so that you can enjoy your lovely cup of Luiza herbal tea from Elon Moreh. If you thought about this information for an additional 10 seconds, you’d realize that your “story” isn’t just incomplete or misleading. It’s maliciously deceptive, and you have poisoned your soul by spreading it. Maybe you were just doing your job, but any job that makes you do these kinds of things is an evil job.

So think about Godin’s words for a moment. How did he type them without his brain bursting from his forehead like an explosively wet melon? What kind of imagination (or motivation) could cause a person to spout such slippery, meaning-free flubdub? Who would be shameless enough to share this malignant nonsense with the world? Like Godin says, the truth is elusive. Nobody can ever really know anything. To you, the layperson, these might sound like the words of a repugnant con artist. To the marketer, it sounds like Thomas fucking Pynchon.

Which is nonsense, because Godin is a much bigger star than Pynchon. They’re both considered among the most creative minds in their respective fields, but Godin’s the one who turned those compliments into something tangible (and endlessly monetizable). His audience is larger by several orders of magnitude. He’s written 18 bestselling books and amassed a fortune of $34 million. Pynchon isn’t a starving artist by any means, but he can’t boast that kind of net worth. He doesn’t even have a TED Talk. Pynchon’s creativity is the kind that gets you admiring mumbles from the stoned barista at the local coffee shop, but Godin’s creativity is the kind that gets you a trip on a private jet to deliver the keynote speech at Davos.

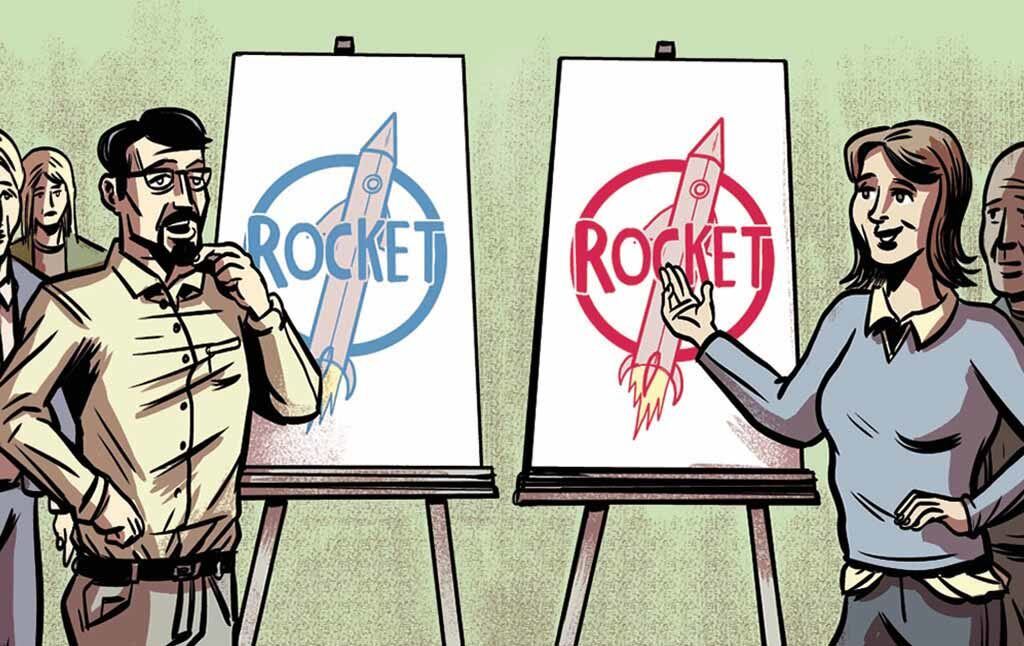

Another mark in Godin’s favor: His kind of success seems more achievable. If you’re a creative young person who likes words, it’s easier to imagine yourself becoming the next superstar marketer than the next postmodern literary hero. Your friends and family won’t laugh at you for saying, “I want to write email newsletters that generate consistent sales,” the way they’d laugh at you for saying, “I want to write thousand-page novels about a misanthropic postman who plays the ukulele.” Americans have a fetish for practicality. A child who enjoys tinkering is likely to be told that the ideal outlet for her talents is a STEM career at Lockheed Martin, just as a child who enjoys drawing will be taught to dream of doing graphic design for Adobe. It’s the Google doodle dream, a 21st-century version of the Renaissance patronage system with woke brands in place of benevolent royals, where expressing your creativity comes first and turning a tidy profit is just a pleasant side effect. There’s no tension between doing your job and doing what makes you fulfilled.

This system gave birth to what professor Richard Florida calls “the creative class.” Back in 2002, his theory of “creativity as a fundamental economic force” was celebrated by business executives and government administrators desperate to show that neoliberalism was compatible with human happiness. A vast new professional field, “spanning science and technology, arts, media, and culture, traditional knowledge workers, and the professions,” seemed to be living proof that society was benefitting from the policy decisions that had been “transforming our economy and culture over the past several decades.” The best part? Our lives weren’t just better because we had more stuff, but because we earned that stuff by doing what we loved.

It’s easy to see the appeal of Florida’s argument. He was tapping into the same idea behind Rose Schneiderman’s famous line, “the worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.” The only difference is that Schneiderman understood her demand to be incompatible with modern capitalism, whereas Florida was (and is) determined to squeeze this roundest of pegs into an immutably square hole.

Even today, after the ideas championed by Florida have led the planet to economic and environmental devastation, he remains unfazed. “I’m not sorry,” he says. “I will not apologize. I do not regret anything.” He claims that his critics “created a strawman.” Meanwhile, in New York, people are homeless at rates that rival the Great Depression, while a quarter-million homes sit vacant. Yet the man whose globally influential think tank invented the Bohemian Index insists, “I’m certainly not the architect of gentrification. I wish I had that kind of power.” He claims to be deeply concerned about “this divisiveness.” He says that today he realizes “we need to develop a new narrative, which isn’t just about creative and innovative growth and clusters, but about inclusion being a part of prosperity.” Like Godin, he has a gift for aphorisms as airy and toxic as a cloud of farts.

Sleazy marketers pretending to be storytellers, unscrupulous real estate developers masquerading as academics, these are the products of a society conditioned to view creativity as an economic force. Godin and Florida embody what the French economist Thomas Piketty calls the “fundamentalist belief by capitalists that capital will save the world.” There’s no inherent conflict between artistic authenticity and corporate profitability! Sculptures and stock options go hand in hand! Be a bohemian, be a brand manager, it’s really all the same! Hustlers like Godin and Florida make lucrative careers out of reaffirming this desperate wish. Unfortunately, as Piketty says, “it just isn’t so…. capital is an end in itself and no more.” The type of creativity encouraged by capitalism is empty and meaningless, a low-calorie substitute designed to satiate our hunger to create (but just barely). The creative class only exists because our collective frustration would boil over into violent revolt if it didn’t.

In his landmark essay “On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs,” anthropologist David Graeber described the “profound psychological violence” a person experiences when “one secretly feels one’s job shouldn’t exist.” Anyone who has ever run a corporate Twitter account or sketched out a comic about blockchain protocols will find Graeber’s insights uncomfortably relatable (he was so swamped by reader responses that he ended up writing an entire book about bullshit jobs). Perhaps you’re technically following your passion—writing words, drawing pictures—but there’s a gnawing sense of emptiness about the whole thing. Like most negative emotions, you’re taught to repress it, to justify it, to explain it away.

Former journalist Dan Lyons, who joined the tech startup HubSpot as a “marketing fellow” after losing his job at Newsweek, witnessed the power of this delusion firsthand. His coworkers—most of whom were the sort of hip, diverse millennials who form the barely solvent base of the creative class—were genuinely committed to doing “meaningful work.” This natural human urge was the mechanism by which they were controlled. As Lyons says:

What I found striking was that you could tell people that it was [meaningful work], and they would just believe it. They wanted to be doing something unique or valuable, and if you came at them with a straight face and said “you are changing the world” they would go along with it.

Lyon’s coworkers weren’t stupid. They just wanted to believe their lives meant something, and having just lived through a global socioeconomic meltdown, they understood the precarity of their position. They weren’t beggars (yet), but they didn’t have the luxury of being choosers, either. As one depressed couple asked Lyons, “was there anything better?”

There wasn’t, and there isn’t (until we achieve socialism), and this explains why people will still aspire to join the creative class until we do. The young marketer who calls himself a storyteller isn’t being disingenuous—he really does want to tell stories. If someone would pay him to tell stories about love and friendship, he would, but if they’ll only pay him to tell stories about antimicrobial underwear, well, he’ll do that, then, if it means his kids can have health insurance. In the meantime, he’ll try to practice his craft as best he can: He’ll study his audience, he’ll learn their hopes and fears, he’ll use every trick he can to convince them, to convert them, to make them feel something.

Does this mean he’s a bad person? The truth is elusive, as a bestselling slimeball once said.

Still, we can say with reasonable certainty that there are some places where the truth will definitely not be found, and the soulless content factories of the creative class are a prime example. George Orwell once wrote that “if a writer is to have an alternative profession, it is much better that it should have nothing to do with writing.” The same holds true for any creative pursuit. Taking a photo or composing a song or drawing a cartoon is a joyful thing for human beings to do, because it allows us to feel like we’re sharing our true thoughts and feelings with the world. But as Orwell says, “no government, no big organization, will pay for the truth.” It’s doubtful that small organizations are any better. Rare is the case when telling someone the truth about a product or service is the most effective way to convince them to buy it. Creative jobs don’t just discourage you from telling the truth—they demand that you tell lies, which taints the essence of what makes creativity so beautiful and satisfying in the first place.

Thus, the best professional advice for a creative person is to avoid the creative professions altogether. A talented writer should refuse to indenture herself to a consulting firm, and become a house painter instead. A gifted photographer should shun the advertising industry in favor of a career as a postman. Instead of seeking outlets for our creativity in jobs that bastardize our most human impulses, we should look beyond the world of work for ways to express ourselves. The urge to create can also be a destructive urge if we don’t question what we are creating, or why we’re creating it, or for whom. It’s far better to write a poem that no one reads than a jingle that sells more missiles.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.