There’s Never A Way To Make It Right

John Thompson’s death is a reminder of how cruel the criminal justice system can be…

John Thompson died yesterday at the age of 55. 18 of those 55 years were spent in a Louisiana prison, 14 of them on Death Row. Thompson was exonerated in 2003, after evidence of egregious misconduct by the New Orleans District Attorney, who had failed to disclose 10 separate pieces of evidence in the case, including a report showing that the perpetrator’s blood type did not match Thompson’s. After the prosecutor learned he was dying of cancer, he admitted that he had intentionally withheld the blood evidence that would have freed Thompson.

Thompson’s case came to national prominence when a jury awarded him a $14 million judgment in a lawsuit against the Orleans Parish District Attorney over their conduct. The vindictive practices of Harry Connick, Sr. (father of Jr.) as head of the office extended well beyond Thompson’s case. For years, Connick had been violating people’s constitutional rights, withholding witness statements that contradicted their testimony, and in one case “actually ha[ving the defendant’s] alibi witness arrested and detained on trumped-up charges, solely to prevent him from testifying for [the defense].” According to the New Orleans Capital Post-Conviction project, under Connick the office withheld potentially exculpatory evidence in twenty-eight separate cases. Connick’s successor, Leon Cannizzaro, has become equally infamous, after jailing crime victims (including in rape cases) who refused to cooperate with police, arresting the investigate staff from the public defender’s office, and forging fake subpoenas.

In 2011, John Thompson’s judgment against Connick was thrown out by the U.S. Supreme Court, in what has been described as one of the court’s cruelest opinions. Clarence Thomas (who else?) writing for the majority, concluded that Thompson hasn’t shown that Connick met the requisite standard of being “deliberately indifferent” to training his staff to comply with their disclosure obligations. Of course, Connick had been deliberately indifferent, and had acknowledged as much himself. He admitted that he hadn’t read a law book or examined court opinions since 1974, that his office didn’t conduct any training on disclosure requirements. Connick even demonstrated that he misunderstood the law himself, believing that no violation could occur if the prosecutor’s failure came about because they were too busy and overburdened.

Clarence Thomas’s opinion was one of the court’s worst, essentially granting prosecutors immunity from civil suits, no matter how deliberate or negligent their misconduct is. John Thompson himself said that while he didn’t care about losing the 14 million dollar award of damages, he couldn’t understand why the court had essentially guaranteed that prosecutors who withhold exculpatory evidence will suffer no consequences:

I don’t care about the money. I just want to know why the prosecutors who hid evidence, sent me to prison for something I didn’t do and nearly had me killed are not in jail themselves. There were no ethics charges against them, no criminal charges, no one was fired and now, according to the Supreme Court, no one can be sued.

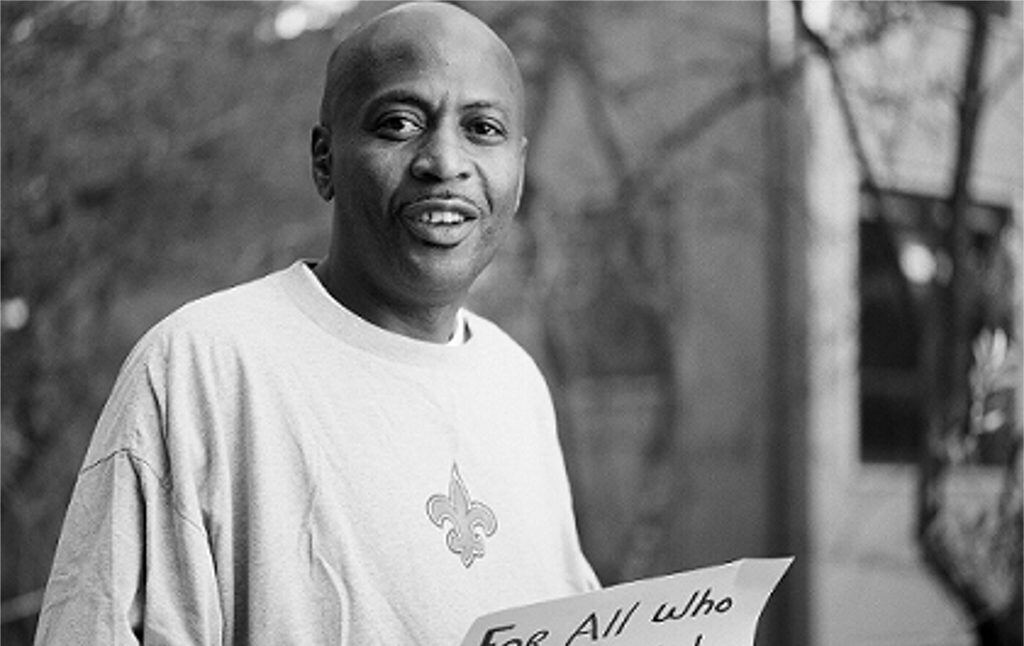

But while John Thompson had every right to be bitter, he wasn’t. Instead, he spent his life after his release helping others in the same situation, founding a nonprofit organization called Resurrection After Exoneration that aimed to help people released from prison (of which there are many in Louisiana) to piece their lives back together. He was a public crusader for prosecutorial accountability, gave talks around the country, and in his post-prison life he committed himself to assisting others. Thompson was, in the words of one of his attorneys, “resilient, resourceful and compassionate in ways that are unimaginable given his situation.”

Thompson was an innocent man, and he cared a lot about keeping innocent people out of prison. But he wasn’t just concerned with people who had been exonerated: despite its name, Resurrection After Exoneration helped all formerly incarcerated people. Thompson saw the way that prison could damage people in ways that were very difficult to undo upon release, whether they had committed the crime or not. “Men come home and the system has nothing in place to help them put their lives back together,” he said. “They need to be reprogrammed because the survival tactics they learned in prison don’t work in the outside world.” The cases of wrongfully accused people are the most sympathetic injustices, but Thompson had the moral courage to care about people whose crimes made them a more difficult public cause.

I had the good fortune to speak with John Thompson twice, first at a talk he gave and then when I was working on “Capital Punishment: Race Poverty and Disadvantage,” an online course about the reality of the death penalty taught by Yale Law School’s Stephen Bright. Bright conducted a long interview with Thompson for the course, and what struck me most about Thompson was his extraordinary dedication and energy. To lose his voice, his righteous hatred of prosecutorial abuses of power, is a tragedy.

Now that John Thompson has died, at only 55, I can’t help but think about how little even that $14 million would have done to right the wrong committed against him. Thompson lost ⅓ of his life to the prison system. When he went to prison he was 22, with two young children. When he left, he was 40, and his children were grown. Thompson wrote about what it was like to be on Death Row as his children were growing up:

Over the years, I was given six execution dates, but all of them were delayed until finally my appeals were exhausted. The seventh — and last — date was set for May 20, 1999….I remembered something about May 20. I had just finished reading a letter from my younger son about how he wanted to go on his senior class trip. I’d been thinking about how I could find a way to pay for it by selling my typewriter and radio. “Oh, no, hold on,” I said, “that’s the day before John Jr. is graduating from high school.” I begged [my lawyers] to get it delayed; I knew it would hurt him. To make things worse, the [day after I was told the date], when John Jr. was at school, his teacher read the whole class an article from the newspaper about my execution. She didn’t know I was John Jr.’s dad; she was just trying to teach them a lesson about making bad choices. So he learned that his father was going to be killed from his teacher, reading the newspaper aloud.

Nothing can make up for this. There is no way to make it right. It was an unbelievably horrific torment, inflicted not just on John, but on his children, too. And there is something about John’s death at 55 that makes it seem even worse. When innocent people are released, sometimes they have very little time to enjoy their freedom. Kenny Waters, whose sister Betty Ann went to college and law school so that she could prove his innocence, died six months after his release. (That fact was apparently so depressing that when a film was produced about the Waters case, his death wasn’t mentioned in the epilogue.) When the exonerated die, one realizes just how irreplaceable what was stolen from them is. Even money couldn’t buy you an escape from mortality, and when the state takes away crucial parts of people’s lives, like the time they would have spent with their young children, there is literally no way to compensate for the loss.

John Thompson’s death should remind us just how brutal the criminal justice system can be, for both the innocent and the guilty, and should encourage us to take up the fight that he committed his life to. There may be no way to truly compensate for taking 18 years of someone’s life, but those who inflict such harms should at least not be immune from consequence.