How TV Became Respectable Without Getting Better

On the rise of Prestige TV…

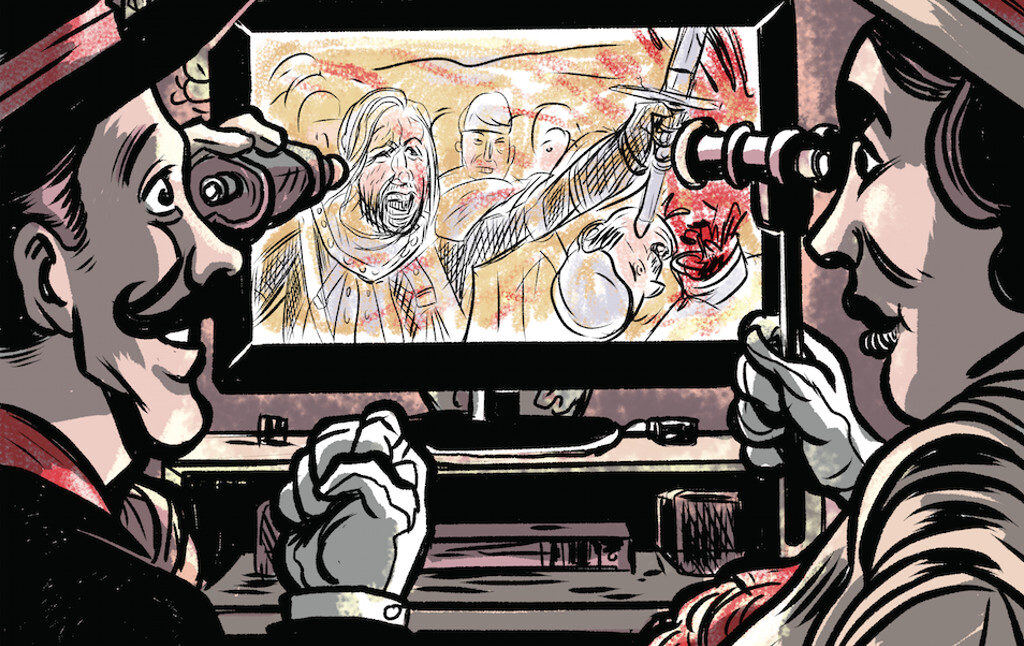

For a very long time, television was bad. A “vast wasteland,” as FCC chairman Newton Minow called it in his now-quaint 1961 speech Television and the Public Interest. Minow went on to ask his audience to sit through an entire day’s worth of television programs. He promised that: “You will see a procession of game shows, formula comedies about totally unbelievable families, blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism, murder, western bad men, western good men, private eyes, gangsters, more violence, and cartoons. And endlessly commercials — many screaming, cajoling, and offending. And most of all, boredom.”

Anyone who took Minow up on his challenge would have been hard-pressed to disagree. For every Twilight Zone there was a My Three Sons and two Lassies. Television had barely come on the scene before people started calling it the boob tube and the idiot box.

Time did nothing to improve television’s quality, variety, or impact on culture. The only real innovation in the medium over its first fifty years was the reality show, which, by the end of the 20th century, was threatening to consume Western civilization entirely with increasingly dystopian nightmare offerings. By the time of George W. Bush’s election it seemed like only a matter of time before primetime network television would consist entirely of live executions and Regis Philbin. But then, when all hope seemed lost, a shaft of light burst through the covering darkness. A shaft of light in the bulbous, gabagoolian shape of James Gandolfini.

The Sopranos changed what television could accomplish artistically. It utilized the serialized storytelling, the depth of characterization and theme of a novel, and the visual sensibility of film. Episodes ended without the pat resolution that defined traditional TV drama. Stories stretched out over episodes and seasons. Characters underwent the sort of transformations that would have confused and alienated the audiences of previous generations of shows that thrived on archetypes. Inspired by show creator David Chase’s accomplishment, a whole generation of creative heavyweights set to putting their own mark on the medium. The Davids, Milch and Simon, created a pair of HBO shows, Deadwood and The Wire, respectively, that failed to match The Sopranos in viewership, but achieved posthumous critical canonization. Then, the network AMC, which originally showed old Hollywood movies to a small audience of nostalgic geriatrics, really managed to copy the Sopranos formula with Matthew Weiner’s Mad Men and Vince Gilligan’s Breaking Bad. These shows achieved levels of popularity and critical acclaim that had never been seen before, and certainly not on basic cable. TV got so good, in fact, that it wasn’t long before the dominant opinion among cultural tastemakers, from Vanity Fair to Newsweek, was that television had surpassed film as the most vital popular narrative art form.

As movie theaters were choked with sequels and reboots and soulless, obscenely-expensive comic book spectacles, the choice to stay home and absorb yourself in a rich, complex extended narrative just made sense. David Remnick, editor-in-chief of that ur-cultural tastemaker the New Yorker, said as much in a letter he wrote to the Pulitzer Prize committee recommending Emily Nussbaum, the magazine’s TV critic, for this year’s criticism award. According to Remnick, television is “the dominant cultural product of our age—it reaches us everywhere and has replaced movies and books as the thing we talk about with our friends, families, and colleagues.” (Nussbaum won that Pulitzer, by the way.)

This new artistic consensus only holds up if you put a rather fat thumb on the scale. Critics who make the case for the superiority of television to film invariably compare their preferred boutique cable or streaming experience to the latest blockbuster hackwork, but this is an absurd and unfair comparison. It ignores the vast majority of television shows, from NCIS: Pacoima to Toddlers and Tiaras to the latest Kevin James fart-fest. You know, the shows people actually watch. The Big Bang Theory, a show that somehow never makes it into articles about the Golden Age of TV, averages over twenty million viewers, most of whom are the same people filling theaters for Transformers: Knight of the Day. A direct, apples-to-apples comparison would be between the best TV shows the medium has to offer and the best films cinema has to offer.

It would be pointless to argue that a given film is objectively better than a given television series. Tastes are relative. The formats are wildly different. The most revealing contrast is between what kind of critically-acclaimed movies are being made and what kind of critically-acclaimed TV shows are on offer. Just in the past few years, we’ve seen a film about the painful coming-of-age of a gay black youth in Miami (Moonlight), a period horror film about colonial America (The Witch), a stop-motion animated film about loneliness and loss (Anomalisa), and a film about an alternative reality where people who fail to find a romantic partner get turned into an animal of their choice (The Lobster).

While there are many kinds of television shows being made at the moment, it’s worth pointing out that a significant majority of critically-acclaimed, so-called “prestige television” shows are about angsty white criminals (The Sopranos, Breaking Bad), angsty white cops (The Wire), and angsty white ad execs (Mad Men). The current generation of prestige shows, which are universally inferior to that first wave by all accounts, rely on an assortment of genre tropes and the template laid by those pioneering programs. Mostly crime. Mostly male. Mostly extravagantly unlikeable anti-heroes whose sheer awfulness makes us feel better about our own, more mundane foibles.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that television shows are, even more than films, advertisements for themselves. Issues of character, theme, story, setting, are, in practice, very often subsidiary to the primary objective of keeping people watching. All the cliffhangers and suspense sequences have less to do with artistic expression than in keeping the audience hooked. Even shows on streaming services like Netflix and Hulu, where binge-watching is the norm, are angling for that second season renewal. A movie can do its own thing for two hours, leave the audience confused or alienated or angry, and everyone involved moves on to the next project. A show that did that wouldn’t get to come back, and therefore wouldn’t be able to complete whatever grand design its creators insist is animating the entire thing. Staying on the air in a fractured media landscape, where the difference between a hit and a quietly-canceled flop is a few hundred thousand viewers, is essential if one wishes to be Part of the Conversation.

As a result, the subgenre of “Prestige TV” has become a tautological concept, with show after show earning the label simply by aping the aesthetic sensibility and glossy production value of the shows that first defined the genre. Everything is brooding, tortured anti-heroes, stillness punctuated by sudden acts of violence, montage and ironically counterposed musical choices. Plus bad writing—really, howlingly bad writing. Kevin Spacey, in his Golden Globe-winning performance as House of Cards’s Frank Underwood, regularly looks into the camera and fake-Southern-drawls some fortune-cookie nonsense like “There’s no better way to overpower a trickle of doubt than with a flood of naked truth.” Jon Hamm’s Don Draper, meanwhile, routinely gifted Mad Men viewers with such high-level insights into the human condition as “People tell you who they are, but we ignore it because we want them to be who we want them to be.” Were epigrams such as these accompanied by, say, a tender swell of orchestral music, it would be immediately obvious how banal and lazily-written they are. But when uttered over the rim of a scotch-glass in a moodily-lit room by an exquisitely-dressed actor, they are, somehow, imbued with profundity.

The dirty little secret of the Golden Age of Television is that the main reason we all know that we’re living in the Golden Age of Television is because we’re told so by an emergent class of TV writers who have risen to prominence in tandem with it. The rise of the internet has as much, if not more, to do with the rise of perceived TV quality than any show-runner revolution. The Sopranos debuted at almost the same moment that the World Wide Web started reaching into the majority of homes, creating an explosion of websites that demanded content directed at a class of office workers who needed something to read to distract them from their white collar drudgery.

And so an army of recappers and critics were called from the digital ether to ceaselessly whisper a constant consolation for the future that never came. After a century of intense economic productivity, you still don’t have space colonies or even shorter work-weeks, but hey, you do have your couch and your Seamless and hundreds of hours of streamable, premium television at your fingertips.

And these new TV shows are not only to be watched, but to be endlessly obsessed over and speculated on: plot puzzles and opaque character motivations offer endless opportunity for fans to take to the web and start theorizing. There are certainly strong incentives in the direction of manufacturing contrived mysteries and intentional plotholes in order to fuel speculation and drive clicks to websites.

Such is certainly the case with the last prestige TV show to dominate the cultural conversation: Westworld. When HBO, the Zeus from whose head the Goddess of Quality Television sprang, debuted Westworld, a show with lavish production detail, acclaimed actors, and a Nolan brother behind the camera, there was no real doubt as to how the recappers and critics would respond. But is there anything truly interesting, fresh, and groundbreaking about Westworld? The pilot seeps through 80 lugubrious minutes of recycled meditations on man’s inhumanity to robot, spiked with gratuitous nudity and violence, and climaxing with one of the cheapest bits of dramaturgy in the prestige TV toolkit. I won’t spoil it for new viewers, but it’s the same kind of tired old stylistic tricks that the genre routinely uses to make a show’s violent, titillating aspects (i.e. the main reason everyone was watching) seem artistic and rewarding. A character monologues optimistically over a montage of her fellow cast members looking stricken or sadistic, all scored with an ironically foreboding ambient score, punctuated by a small act of violence and an abrupt fade-to-black. There’s an ominous low tone that signals you’re watching Something Very Serious and Important. Behind it, you can almost hear another voice, the voice of the internet opinions to come, assuring you that all of this is as it should be in the best of all possible worlds.

After a few episodes, the fundamental insufficiency of Westworld as a piece of art became impossible to ignore even to the most fervent television evangelist, but the flagship prestige show on the flagship prestige network was simply too big to fail. So the Westworld articles spit out by content-mills focused mostly on decoding the show’s central plot mysteries (Who is the Man in Black? What is the Labyrinth? Who killed Arnold?), rather than analysis of banalities like “character” or “theme” or “emotional resonance.” The glossier outlets insisted that Westworld’s wooly-headed pretentiousness and compulsive mystery-mongering were actually a satire of prestige TV tropes. (“An exploitation series about exploitation, full of naked bodies that are meant to make us think about nudity and violence that comments on violence”—Emily Nussbaum) Anything to avoid the obvious fact that everyone watched the show because it had boobs and blood and because everyone else was watching it and it’s so lonely out here.

One of the bitterest of the many bitter ironies of the digital age is that the explosion of television options and web-based platforms featuring cultural writing has led not to a flowering of creativity and a golden age of critical insight, but an all-consuming monoculture. A cargo cult where the trappings of a few groundbreaking cable shows from early in the millennium have hardened into tropes that power a legion of inferior imitators. Even more disturbingly, dozens of writers at dozens of outlets that depend on clicks and engagement have forged a hive-mind of positivity about the whole thing, assuring their audience that a diet of cultural junk food is just as healthy as balanced meals, because television is the medium best suited to the lives of internet-addicted office drones. Hopefully, as the Golden Age of the Golden Age of Television recedes farther into memory, and as viewers’ working conditions grow more and more intolerable, there will be a collective realization that we deserve better than Prestige TV.

Illustration by Mike Freiheit.