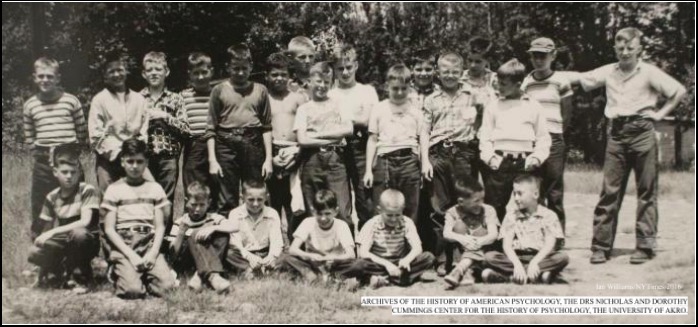

In the unusually hot summer of 1954, social psychologists Muzafer Sherif, Carolyn Wood Sherif, and a group of research assistants conducted a social experiment at Robbers Cave State Park in Oklahoma. Recruiting 22 boys—all 12 years old, white, Protestant, and middle-class—the Sherifs and their colleagues divided these subjects into two groups. Keeping both groups separate from each other, the boys were encouraged to play cooperative games within their own group, leading to the development of separate group identities and team names. After several days, the two groups were brought together to compete for prizes, awards, and privileges over the losing team.

The introduction of competition, particularly when one group was rewarded at the expense of the other, led to so much friction that verbal taunting and name-calling quickly turned into stealing, vandalism, and violence between the groups. The researchers were forced to separate the boys when one group burned the flag of the other and both teams began throwing rocks at each other.

As planned, the researchers then introduced scenarios that required cooperation between the two groups. One scenario required the boys to push a broken-down truck back to the camp site. Only by both teams “putting aside their differences” and working together could they complete the task. To the researchers’ excitement, the boys did work together, successfully pushing the truck back to camp, which also managed to greatly reduce the animosity between the two groups. By the last day of camp, the boys from both groups sang Oklahoma together and cried on the bus back home, sad because the camp was coming to an end.

While normally cited as a rejoinder to the persistence of racial division (as part of a larger concept in social psychology known as “realistic conflict theory”), the Robbers Cave Experiment also provides us with a way of thinking about climate breakdown, the greatest challenge to humanity in the 21st century, and potentially the greatest opportunity for improved social relations. In a complex geo-political landscape of nation-states within a neoliberal global economy, states and communities are often in simultaneous competition and cooperation, fighting shared enemies and disagreeing on fundamental questions of human and environmental freedoms and rights. Of course, while the nation-states and communities of the world don’t fit as cleanly into the metaphor of the Robber’s Cave as its adolescent participants, climate change does seem to be our broken-down truck—it’s a task that can only be accomplished collectively. All groups must work together or face an unrecognizably hotter future, potentially a hothouse earth, jeopardizing organized human society. By combining forces to confront the challenge of climate change, we could be, in the words of Carl Sagan, “no longer at the mercy of the reptile brain,” instead uniting to save (potentially) all complex life on this pale blue dot, and fundamentally changing ourselves in the process.

Researchers looking at future climate pathways understand that social and economic conditions have to be considered if we are to better understand potential future greenhouse gas emission scenarios, such as whether we should expect a one or four degree Celsius increase in global surface temperature. From this recognition, researchers have developed the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), five hypothetical paths that nation states and the global community can pursue in confronting climate change. SSP1 is the ideal scenario, where all nations work together (like the boys letting go of their rivalry in order to push the truck to camp) rapidly transforming society for the benefit of all. SSP2 is a half-hearted attempt, where some nations eagerly cooperate while others are less interested, and, with some willing to push and some refusing, the truck only moves a short distance. SSP3 is where rivalry wins out, and, rather than pushing for rapid mitigation and adaptation, nations and communities fight each other while the earth continues to warm. SSP4 and SSP5 present more nuanced visions, in which one type of cooperation—such as reducing emissions or supporting those facing the impacts of climate change—is prioritized while the other is excluded. Essentially, the boys would struggle to push the truck while leaving others behind.

For a deeper look at the implications of the Robbers Cave Experiment when it comes to cooperation against seemingly impossible odds, we should turn to its precursor, the “failed” attempt at Middle Grove. One year earlier, in 1953, the same researchers tried the same experiment on two groups of boys in Middle Grove, New York. However, in the Middle Grove study, instead of competing against each other, the boys recognized they were being manipulated to dislike each other by the researchers, and even called out the adults for their dishonorable behavior. The two groups of boys refused to compete, working together and resisting the researchers’ attempts to create competition and sow discord. As Gina Perry describes in her book The Lost Boys: Inside Muzafer Sherif’s Robbers Cave Experiment:

Anger was supposed to spill into violence, fighting, and retaliation…In the final stage, when the hostility and hatred between the boys had reached fever pitch, Sherif planned to set fire to the forest so the boys would be forced to cooperate…in his efforts to get one group fighting the other, Sherif and his staff had cut the rope on a precious flag, ‘stolen’ items of laundry, and smeared and demolished the food set up for one group’s dinner, all to trigger a fight between them. Each time, the boys’ irritation and anger was transitory. The only enduring resentment among the losing Pythons [one of the teams of boys] was against the staff. Now the Pythons were complaining they had been treated unfairly. Instead of blaming the Panthers [the other team], they attributed their loss to the actions of the adults…

Social psychologist M. Bilig, in critiquing the Robbers Cave study, states that it really should be understood as a social experiment between three groups: the two participant groups and the overwhelmingly powerful researchers who dictate the terms and create competition where it doesn’t need to exist.

With this new imagery, we can identify the overlooked third group in our own Robbers Cave/climate crisis experiment, a group invisible to many because our mainstream historical narratives often omit their power and influence. But we can identify them easily by looking at the historical conditions that have created the climate catastrophe: namely, the rise of industrial capitalism and the creation of modern nation-states. Just like the researchers, our “third group” are those with a monopoly on power.

Historically, the wealthy and powerful were the ones who enclosed commonly-held lands, forced peasants into industrial factories, erected borders to control migration and the flow of resources, and colonized most of the planet, destroying indigenous knowledge and forcing collectivist communities to compete for their own survival. In Ashley Dawson’s book Extinction: a radical history, he describes capitalism as “not necessarily more immoral than previous social systems in regard to cruelty to humans and gratuitous destruction of nature. [However,] as a mode of production and social system, capitalism requires people to be destructive of the environment.” We can see this in the supposed logic of economic growth: our economy must always be in a process of expansion, driven by relentless competition. This driving logic of competition can be traced to every level of social-economic relationship: the miner competes for work, the business competes for customers, the corporation fights for domination of the market. Failure to grow, to extract, to exploit the earth’s resources would mean defeat, and thus profits and influence are used to continue the cycle of destruction and growth.

So, how do we reconcile the truths of the Robbers Cave Experiment with those of Middle Grove? And how do these experiments help us see a path forward, beyond the logic of capitalism and competitive nation-states? For both experiments the underlying premise is the same: only together can we stand up for our collective dignity and well-being against planet-destroying forces both animate and inanimate. Keeping the climate below a 2-degree Celsius rise in temperatures will necessitate sweeping and rapid global grassroots action: restructuring our energy infrastructure and energy use, transforming our relationships with each other and with our environment, and radically altering our economic system—all massive undertakings without historical precedent.

Similar to the adolescents in both experiments, moving forward necessitates cooperation and solidarity, not a forgiving of past wrongs per se but a restorative justice process by which we understand past violence as a product of oppressive systems designed to pit us against each other via the creation of the physical and social borders of the state, race, gender, sexuality, etc. in other words, the artificial competition of the capitalist experiment. This strategy of division and violence continues to obstruct free movement, impede democratic decision-making, encourage right-wing extremism, all so corporations can maintain a cheap labor pool, extract resources without oversight, and assure future shareholder profits. In the words of anarchist anthropologist David Graeber, capitalist “globalization” is limited to the “movement of capital and commodities, and actually increases barriers against the free flow of people, information and ideas… if it were not possible to effectively imprison the majority of people in the world in impoverished enclaves, there would be no incentive for Nike or The Gap to move production there to begin with. Given a free movement of people, the whole neoliberal project would collapse.”

Understanding how humans will overcome the artificiality of our hierarchical “differences” and unite under a shared mission continues to perplex many climate researchers and activists. This task is only achievable through recognizing, calling out, and confronting our shared oppression and the systems that dictate the terms of our lives. No matter where you go across the capitalist world, the overwhelming majority of humans spend their days exchanging their labor for money, and money for survival (or something close to it). Much of waking life is spent working or consuming for someone else’s profit, and yet many people remain oblivious to the fact that our lives haven’t always been like this. According to sociologist Juliet Shor, “Before capitalism, most people did not work very long hours at all. The tempo of life was slow, even leisurely; the pace of work relaxed. Our ancestors may not have been rich, but they had an abundance of leisure. When capitalism raised their incomes, it also took away their time.”

The dramatic increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, which today’s researchers point to as the origin of human-caused climate change, started with the introduction of industrial capitalism and a dramatic increase in productivity. Unsurprisingly, the 2007 recession saw a dramatic decrease in US emissions, which largely continued until the economy recovered. A unifying movement to reduce emissions must be a movement that opposes endless-growth productivity and embraces leisure, unions and worker’s struggles for higher pay, greater benefits, and shorter workdays, in other words—the shared desire of all working-class people everywhere, to spend less time producing (i.e. less time working) and more time with the people we love, doing the things that bring us joy—all which have been shown to reduce emissions.

The process of mass awakening to the oppressive role of capitalism (i.e. the “third group”), not as some shadowy conspiratorial evil but as a set of real-life class interests, may seem overwhelming, almost abstract. However, the first step to confront these forces has, and will continue to be taken by regular people struggling for better living conditions. A few recent examples: Harlan County, Kentucky has been the epicenter of coal miner strikes dating back a hundred years, and now, as coal mines close due to an increase in natural gas production, miners have blocked a coal shipment for owed wages. This particular ongoing struggle has gone largely unnoticed by the environmental movement, even when the implications are glaring: workers have shut down environmentally destructive corporate infrastructure for the means to a better future for themselves and their families. Similarly, Greta Thunberg’s skolstrejk för klimatet, or ‘school strikes for climate,’ follows a similar refusal to participate for the sake of the wellbeing of all children forced to grow up on a warming planet. This framing—centering grassroot movements that focus on improving the material conditions of everyday people—challenges mainstream incremental environmental reforms which perpetuate existing power dynamics. It provides a counternarrative to the belief that market-based solutions, such as carbon pricing and cap-and-trade are effective, that state-level policies which exclude the voices of the oppressed and marginalized are acceptable, and that uprisings which oppose market-based solutions, such as the ‘Yellow Vest’ protests, are anti-environmental.

We humans want to be free to do what makes us happy, spend time with the people we love, live healthy lives, and enjoy dignity and justice. Climate change jeopardizes all of these core desires. Envisioning a world in which these core desires are given priority, a world antithetical to the logic of capitalism, will help us bring about a global class struggle that will address the existential threat of climate change and the further deterioration of our lives. In the Sherifs’ experiments, it was the boys’ desire to improve their immediate conditions, whether by moving the truck or figuring out why their possessions were destroyed, that ultimately united them, not moralistic arguments or existential guilt and fear. However, it was only the Middle Grove boys, who joined together to challenge the forces sowing division and attempting to profit from their misery, that ended the experiment and achieved a level of freedom they had never achieved before.

Perry describes the outcome of the Middle Grove rebellion: when the boys realized that the other team wasn’t responsible for the destruction of their belongings, they initially didn’t know who else to suspect. They felt fear of their unknown assailants, while, at the same time, experiencing a sense of purpose in identifying the culprits. Once they’d solved the crime and turned on the adults, the researchers acknowledged that the experiment had failed and simply left the boys alone for the remainder of the camp. “There was a sense of freedom…” writes Gina Perry. “Brian remembered the relief of all being back together as a single group, and wondered if it brought them closer together. ‘It reminds me of that sense of kinship you read about, when strangers have been through an experience together and they develop a bond. When it came down to it, we stuck together didn’t we?’”

Photograph by Josh Edelson, Getty Images

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.