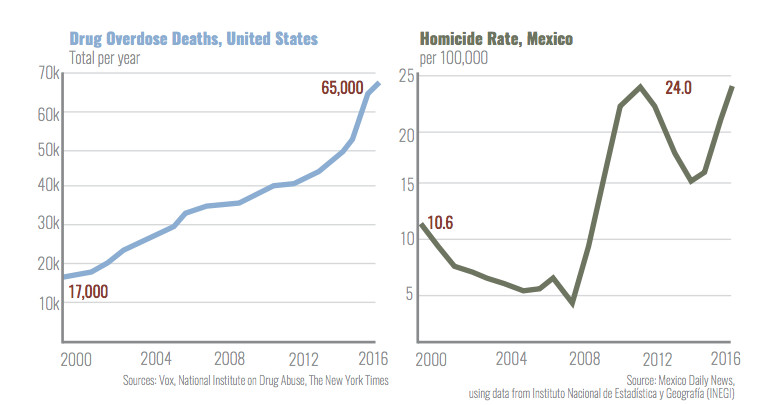

In 2017, two countries hit a milestone. In Mexico, there were 29,168 murders, the highest number on record. Across the border in the United States, nearly 70,000 people died from drug overdoses, over three times as many as were dying annually less than two decades ago. More Americans now die every year from overdoses than died in the entire Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq wars.

There is, of course, a link between Mexico’s murders and America’s overdoses. The murders are rising because of wars between ever-more-brutal drug cartels, who are competing to ship the products on which Americans will overdose. Mexico’s murder rate is slightly deceptive, because it varies significantly across the country, and some areas experience far less crime than many other Latin American countries. But in states like Baja California, the homicide rates match those of the world’s most violent countries. Unsurprisingly, the areas with the highest rates of violent crime tend to be those near major ports or U.S. border crossings, or areas which have some other strategic value for the drug trade. The state of Guerrero, where more than half of Mexico’s opium-poppies are grown, has seen its murder rate escalate over the same period that heroin overdoses have skyrocketed in the U.S. It is strange to think that the deaths of people so far apart geographically—a taxi driver in Acapulco, a struggling addict in Kentucky—could be so intimately connected.

Everyone has heard the gruesome stories about cartel violence in Mexico, which is not just shocking quantitatively but also qualitatively. People beheaded, boiled alive, fed to wild animals: The Mexican notas rojas graphically document the depravity and extremity of cartel killings, which terrify rivals and civilians alike. But the lurid spectacle of border state violence is not something Americans should feel comfortably distant from. One big reason for the ferocity of inter-cartel competition is because Mexico, a highly unequal country where nearly half the population lives in poverty, happens to be situated next to a very rich country willing to pay high prices for an illegal product. There is a certain “logic” to drug violence: If there are fortunes to be made from a commodity that can only be provided through criminal enterprise, people will desperately seek those fortunes through whatever means are necessary. There are political, economic, and cultural forces that contribute to a growth in violence, but while the causes are complex, they are not random or inexplicable.

Before trying to analyze those causes, though, we should make sure we truly appreciate the human toll. As always, behind the statistics are lives, and we can take a moment to think about the level of human suffering that stems from the entire process of manufacturing, distributing, and ingesting illegal drugs. Mexican border cities like Reynosa and Juarez have turned from lively border towns into sad, despondent ganglands where fear rules many people’s lives. Of course, it’s important not to excessively caricature the situation: Even cities with high murder rates aren’t continuous gun battles 24 hours a day. The residents of these places still go out in public, throw parties, attend school, and so on; a bold tourist may still visit on the right day and have a more or less normal experience. Nevertheless, in the areas they control, the power of cartels is one of the dominant facts of everyday life. Cartels are the final arbiters of most of what appears in print: A journalist who writes the wrong thing can expect to receive a threatening phone call, or even a summary execution. Many Mexican journals have shuttered, or have been reduced to simply putting out carefully-worded catalogs of daily murders. Bodies are left in public places, clearly as a message to someone, though it is often unclear to whom. If you fall afoul of the cartel—and you may well do so without even realizing it, or because they’ve mistaken you for someone else—not only you, but your entire family may be at risk, down to your little children. This past summer—to give just one example—a family of five, including four children aged between five and 10, were murdered in Coatzacoalcos because the cartel suspected that the father, an out-of-work taxi driver, had acted as a lookout in an attack by one of their rivals.

All of this is just the suffering that occurs from living alongside criminal trafficking syndicates. Then we have the human consequences of drug use itself, which is felt on both sides of the border. The 70,000 who die annually in the U.S. are people’s parents, children, friends. Many are people who struggled hard to free themselves, to avoid a fate they could see coming, but who were unable to escape addiction. It’s hard to conceive of what the attempt to free oneself is like, the near impossibility of using sheer willpower to overcome a dependency that is chemical in nature. Journalist Ioan Grillo quotes an addict friend: “Imagine the worst flu and multiply it by ten. Then, know you can make it go away with one more hit.” Who could resist a medicine that instantly relieves the most extreme torment? And for many addicts, it’s not simply the physical torment of withdrawal that drugs alleviate: it’s the deep psychological trauma of past abuse, of profound depression, of a consuming, self-annihilating sense of failure. Whole American communities have turned into places of death and dependency.

Repairing the lives of addicts, and ending the carnage caused by the drug trade, is a morally urgent issue that requires a humane, careful, and immediate political response. Sometimes, when we think about U.S. drug policy, it’s easy to get caught up in abstract arguments about whether the government should have the “right” to regulate individual drug use, or cultural debates about whether the use of certain drugs has net positive or negative impacts for society. It’s not that these questions are entirely worthless, but they are, at best, secondary concerns. The overwhelmingly more important question is, what can we do to stop all these deaths from happening? What will actually work?

To call the drug trade a “black market” doesn’t accurately convey its magnitude. The annual revenue from drugs in Mexico is estimated to be as much as $29 billion. This, according to author Ioan Grillo, makes it second only to oil as a source of foreign currency in Mexico. We are talking about production and distribution on the sophisticated scale of a major industry, but all carried out in secret, off the official books. The term “shadow industry” is perhaps the best way to conjure up some sense of the drug trade’s scope and complexity.

It is going too far to say that the U.S. is exclusively responsible for “creating” the violence in Mexico, as if there were no powerful players in Mexico with moral agency of their own. But there is no denying that our government’s draconian drug policies, coupled with our citizenry’s enormous appetite for drugs, have played an outsize role in how Mexico’s economy and political landscape have developed over the last few decades. A brief, whirlwind tour of the history of the Mexican drug trade will give us some sense—however oversimplified—of how the present situation came about. As we all know from Narcos (those of us who had the stomach to watch it, anyhow), Colombian cartels dominated almost every stage of the drug trade in the 1980s. The public hype around cocaine, coupled with its illegality, conspired to make its market price incredibly high. However, when the DEA began concentrating heavy enforcement along the sea routes between Colombia and Florida, the Colombian cartels began outsourcing their transit operations to gangs in Mexico, who could move product across the porous U.S.-Mexico border. Over the next decade, these Mexican couriers grew in power, eventually wresting effective control of the U.S. drug market away from the Colombians. This development had two major effects. One, it resulted in the rise of incredibly violent Mexican drug cartels, who now wage bloody territorial wars for control over major smuggling corridors. Two, the sheer amount of money in the air has served to entangle the Mexican state in the drug trade at virtually every level. The complicity of military and governmental officials was needed to move drugs on a large scale, and the easiest way to ensure this complicity was by promising them a share of the profit. (The threat of assassination, or the kidnapping and torture of one’s family members, can also be a powerful motivating force.)

The important thing to understand about the modern drug trade— something which is occasionally lost in mainstream news coverage—is that it is not simply the tale of rogue criminal groups that under-resourced governments struggle to neutralize. It is also the story of institutional capture, the creation of what are effectively “narco states.” Economic and governmental elites in Mexico facilitate, and profit from, the drug trade. This makes the big-picture spectacle of Mexico’s violence difficult to interpret at any given moment. Determining which actors are collaborating with each other, in the absence of conclusive evidence, often boils down to guesswork. Mexican journalists have long speculated that the national government has covertly backed the Sinaloa cartel, for example, as a means of stabilizing and controlling the drug trade. On a more local level, drug cartels, military officials, and state and municipal governments may have complex webs of alliances and rivalries. This sometimes results in jaw-droppingly bold false-flag operations: For example, in 2010, the warden of a state prison near Torreón, Coahuila temporarily released 17 armed prisoners and sent them on a mission to murder civilians, in order to “bring heat” on the drug cartel that controlled the territory. (This first came to light when the falsely impugned cartel released a video of themselves torturing a confession out of one of the police officers involved, but the warden herself later confirmed the story.) The various players are so intertwined that it is sometimes hard to tell the difference between when the cartels are doing dirty work for government, or the government is doing dirty work for the cartels. The mass kidnapping and suspected massacre of 43 students from a rural teacher training college in Iguala in 2014, for example, defied straightforward explanation and continues to generate a wealth of theories: The students were abducted by a cartel, but the cartel was evidently cooperating with police and acting on the orders of a local mayor, and there is some evidence suggesting that federal military officials may have been involved as well.

The Mexican state thus has duelling incentives with reference to the drug trade. There is pigheaded pressure from the U.S. to crack down hard on drug traffickers: As in many parts of Latin America, the U.S. has extensively deployed stick-and-carrot diplomacy over the past few decades to force combatting narcotraffic to the top of the Mexican government’s agenda. The DEA frequently carries out operations within Mexico. But there are also many actors within the Mexican state who profit from the drug trade and wish to see it continue running in their interest; or who recognize the obvious danger and clear futility of attempting to stamp it out. The public-facing policy of the national government, particularly beginning with the presidency of Felipe Calderón, has been to wage war on the drug cartels, usually by deploying federal troops and police to cartel-controlled regions. (As described by journalist John Gibler, Mexicans draw a clear distinction between la guerra del narco, the government’s “war on drugs,” characterized by the ostentatious public deployment of troops, and la narcoguerra, the “drug war,” the street battles for territorial control among drug cartels and their various allies.) This militarization has only served to cause further problems. There are, on the one hand, the predictable problems that arise during military occupations: extrajudicial executions of suspects, and miscalculations that result in massacres of innocent people. And then there are the problems that arise when military units start collaborating with the cartels and their allies: That’s when you get deliberate massacres and assassinations, carried out for some strategic purpose in la narcoguerra. The military, too, has proved to be not only an ally, but a fertile recruiting-ground for the cartels. Many soldiers who decide that military life isn’t their exact cup of tea transition easily into the ranks of criminal organizations. One of the most infamous cartels, Los Zetas, was originally founded by former members of the Special Forces.

Well, then: Is the solution to “clean up” the Mexican government and the Mexican military, weed out the bad apples, and just make everyone start taking the eradication of the cartels seriously? You wouldn’t be stupid for thinking this, inasmuch as generation after generation of American policymakers, nominally well-educated, have thought the exact same thing. But to attribute the situation in Mexico purely to endemic “corruption”—or to characterize “corruption” as an easily understood and simply rectified phenomenon—is a mistake. The massive profit incentives of the drug trade make it inevitable that Mexican citizens will participate in it, especially in areas where the licit economy is depressed or inaccessible to most people. It is equally inevitable that Mexican officials will be tempted—or, if not tempted, threatened—into some level of direct or indirect collaboration. There have been numerous purges of the military and police, to no avail. And even in some wildly improbable alternate universe of superhuman, squeaky-clean government and military officials, vigorously prosecuting the end of the drug trade, the battle would still be a hopeless one. After all, U.S. and Mexican officials are currently capturing more drugs—and indicting more drug kingpins—than ever before, but this has had no appreciable effect on the amount of drugs making it into the hands of users in the U.S. And it’s only resulted in more murders in Mexico.

The problem is what analysts have described as “the balloon effect”: If you push an air bubble down in one place, it will pop up somewhere else. Police the seas around Florida, and the trade moves to the land border. Cut off a smuggling corridor in one municipality, and the cartels will begin fighting over a different municipality. Capture one drug lord, and others will rise to take his place. Destroy more supply, and the price of the surviving product only rises, and the fresh influx of money brings new players into the drug trade’s fold. While demand for drugs in the U.S. continues to increase, and enforcement in both Mexico and the U.S. continues to artificially inflate the market price, the drug trade will remain wildly lucrative, and people will be willing to run considerable risks to get their cut. And in this bewildering climate of violence, all sorts of people will be killed: cartel members, drug dealers, police, and federales, yes, but also journalists, students, migrants, activists, uninvolved bystanders, random community members unlucky enough to have seen the wrong thing, to be related to the wrong person, to be suspected of having given the wrong person a lift, or a haircut, or a hand signal.

Given how closely U.S. policy and Mexican violence are intertwined, U.S. ignorance and apathy is a major obstacle to addressing Mexico’s problems. People are lazily fascinated by drug lords like El Chapo, either because they find the combination of wealth and ruthlessness to be glamorous, or because of some stupid, childish idolization of violent gangsters as countercultural Robin Hoods fighting The Man. There’s considerably less interest in imagining the lives of the other players in El Chapo’s story: his victims and his enablers. Mainstream media outlets devote very little space to the Mexican drug war, even though some of the worst violence is occurring directly on the border, a stone’s throw from U.S. cities. (As Current Affairs has pointed out many times, with great chagrin, the only news outlet that actually reports on violence in Mexico on a daily basis is Breitbart.) The Trumpian right is eager to use this violence to incite fear and demonize immigrants, but beyond simply branding Trump a racist, the left has yet to come up with a convincing counter-narrative that actually takes this violence seriously and treats its mitigation through policy as a matter of moral urgency. Many left-leaning U.S. Americans have only the vaguest notion that people are being slaughtered at insane rates in certain parts of Mexico, and that this has anything whatsoever to do with us.

The most sympathetic reason for this lack of interest is that we have been distracted by our own domestic drug problem, which we are only beginning to grapple with. The idea that addiction is a medical and social issue, rather than a criminal one, has taken a long time to gain any kind of public traction, and this inward focus has perhaps prevented us from looking to the broader global context of our own national suffering. That said, there is also considerable reluctance to confront the fact that casual, recreational drug use, just as much as “addictive” drug use, has fueled the drug war, and that a lot of us have, indirectly, been pouring money into the war-chests of some of the world’s most violent criminal organizations. Marijuana, for example, continues to represent a huge percentage of the Mexican drug trade, by some estimates accounting for as much as 60 percent of the cartels’ profits. Sure, we can blame our government for causing this whole mess by making drugs illegal, but it still doesn’t quite absolve us of blame as individuals. If the government declared pineapples illegal tomorrow, that would be incredibly unjust, but we’d still bear some moral responsibility if we then started paying murderers to smuggle us pineapples.

However we assign the relative portions of blame between consumers, governments, and cartels, the important conclusion is that ending the drug war is not a mere “personal freedom” issue. It’s a matter of life and death for many tens of thousands of people, and as such, it needs to be a major part of any left political platform. At the moment, the Democratic Party’s agenda says precious little about drugs beyond the need for increased access to addiction treatment. But it’s important to see drug prohibition itself as a serious problem, and to understand addiction not as an isolated phenomenon, but alongside the other corresponding social ills that have resulted from decades of policy choices, from racist policing practices to mass murder across the border. However one personally feels about drug use, the drug war has been immoral, and the left must be committed to ending it. At a time when Donald Trump (who recently proposed implementing the death penalty for drug dealers) is dragging us back toward the brutal “law and order” approach that has resulted in such catastrophe and bloodshed, it’s more important than ever for progressives to put comprehensive drug policy reform at the top of their agenda.

It’s depressing to consider just how much harm has been done by the simple-minded effort to ban drugs rather than regulate them. Obviously, banning a commodity often makes the market for it more profitable and more violent. It confers power on the world’s least scrupulous people, and uses physical force as a means of dealing with a medical and social problem. And, of course, in a country with racially biased sentencing practices, every increase in enforcement efforts will, continuing the neverending pattern of American history, come down hardest on people of color. It’s actually not true that prohibition can “never work,” if “working” is strictly defined as “reducing drug use” rather than “making a better society than the one where people were using drugs.” As criminal penalties increase, some would-be users and dealers will be deterred by the heightened risk, although both drug use and profit-seeking are often compulsive rather than rationally calculated. But prohibition probably could “work” if you built a large enough, brutal enough, and invasive enough police state. It’s just that in order to get anywhere close to effectively stamping out drug use through criminal enforcement, one would have to inflict devastating social costs. It’s true that there may be less crime if you put everybody in prison, just as your house would have fewer maintenance problems if you burned it to the ground, but the benefits are outweighed by the somewhat disproportionate costs.

It’s sort of hard to actually picture what this totalitarian prohibition state would even look like, though, because as it is, a long history of vigorous enforcement in the U.S. hasn’t even lowered rates of drug use, much less eliminated them. Our policies have succeeded in creating a cruel and omnipresent criminal justice regime, but with nothing to show for it. Instead, the problems have gotten exponentially worse, as drug users have been put into the criminal system instead of being given assistance. As their lives deteriorate, and their sense of shame and hopelessness increases, so does their dependency. Their criminal records often keep them out of housing and jobs, and essentially ensure the likelihood that they will turn to small-scale dealing to help fund their continued using.

There are reasons to believe that decriminalization or legalization would actually help most addicts recover. Johann Hari’s Chasing the Scream provides accounts of pilot programs in Switzerland and government policies in Portugal that appear to show promising results. But even if drug use under legalization remained about the same as the status quo, a clear moral case for legalization can be made in terms of violence reduction alone. As cartels continue to fragment and vie for territorial control—a problem that is actually made worse by breaking up cartel leadership with high-profile arrests—the country’s violence will not diminish, and might become even more extreme.

To be clear, it would be naive to think that legalizing drugs will solve the problem of violence in Mexico in a single stroke. Existing criminal syndicates are not going to ruefully hang up their assault rifles overnight. If the drug trade becomes less profitable, cartels will increase their focus on things like labor and sex trafficking, and the smuggling of migrants across the border. (We can alter some of the incentives for those activities by changing our immigration policies, but that’s another discussion.) Locally, at least in the short term, it seems likely that criminal groups will rely more heavily on things like kidnapping and extortion—which are already very serious problems in many areas—to sustain themselves. This is the modus operandi of gangs like MS-13 in Central America, for example, which have only a very limited and tenuous involvement in the transnational drug trade. Figuring out how to respond to these developments will be very hard, in the way that handling violence is inherently incredibly hard. There will also, of course, always be some room to make money smuggling drugs: Even if drugs were legalized in the U.S., there would be presumably be some level (probably quite high) of government regulation, which always creates openings for black markets.

That said, legalization is an indispensable and urgent piece of any conceivable plan to reduce violence in Mexico. We can imagine the violence in Mexico as a gigantic raging fire, being fed by a steady torrent of gasoline. If we switch off the gasoline, that by itself won’t put the fire out: Extinguishing the blaze will still require a huge amount of coordination and effort. But if we don’t switch off the gasoline, the fire will never go out. The idea that we can fight the fire, without addressing the steady stream of fuel that’s being continually poured onto it, is absurd. Heavy drug enforcement and high demand for drugs in the U.S. interact to make drugs wildly profitable. Because the trade is illegal, and heavily policed, selling drugs is also dangerous, and the potential for violence is thus inherently very high. We have to make the drug trade both less profitable and less dangerous, in order to alter these incentives in any meaningful way. Increased enforcement does not work; increased enforcement has never, ever worked, not once in the entire history of the drug trade. Legalization is the only plausible option. After that, of course, much more remains to be done. We should seek to reduce the demand for hard drugs in the U.S. by humane, social means that truly address the root causes of addiction. And there is no conceivable long-term solution to violence in Mexico that does not involve addressing factors like poverty, inequality, political disempowerment, lack of decent work, and family separation, all things that U.S. economic, immigration, and foreign policies have contributed to.

It’s common to call the War on Drugs a “failure.” It certainly is that, as attested to by the tens of thousands of bodies piling up each year in the U.S. and Mexico. But more importantly, it’s a crime. It’s a deliberate policy choice, one now being embraced by the Trump administration, that inflicts needless suffering on some of the world’s most vulnerable people. It’s important that those of us in the United States recognize that when we talk about this “failed policy,” we are not just talking about the failure to help addicts in our own country, but the countless murders of Mexicans that are occurring because of America’s political decisions and consumption habits. There needs to be a greater recognition of the shared fates of the U.S. and Mexico: Our deaths and their deaths both matter, and it can no longer be acceptable to pretend that anything that occurs on the other side of the wall has nothing to do with us. Because our country contributes to violence in Mexico, we have a responsibility to help stop it, and if that means pushing for full legalization in order to break the power of cartels, so be it. The drug problem is more than a “problem,” it’s a systemic disaster that spans multiple nations. Its costs are not just in overdoses. This is a human rights issue: not merely the right to privacy or bodily autonomy, but the still more urgent right of human beings to live lives free of needless criminal and state violence.