Let us try a thought experiment. Let’s suppose that on a day in the near future all of America’s political elites spontaneously agree to be cordial in public, with the media’s biggest talking heads quickly following suit. Let’s imagine they also sign a document agreeing to finally put their differences aside and work together in the common interests of the American people. Let’s suppose (bear with me) that the document officially commits them to put evidence, common sense, and moderation ahead of petty squabbles and country ahead of party. To immortalize this historic treaty, they establish a new statutory holiday called Unity Day—a kind of centrist Bastille Day—commemorating the end of political contention and marking the eternal reign of Reason. At the event’s inauguration, statues are unveiled in honor of the philosophes at the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Brookings Institute whose collective wisdom finally toppled partisanship’s ancien regime. In an image that will surely echo throughout the ages, a bespectacled David Brooks stands atop the National Mall to unveil a towering monument to moderation. Henceforth, the word “partisan” will be Washington’s most vicious slur and all but a few eccentrics will conduct themselves in a manner that ensures they are never tarred with it.

Having imagined all of this, let’s ask ourselves: how much would life for the average person meaningfully change if this little farce were to become reality?

If a single cliché unites all of establishment political discourse in America, it might be the idea that the greatest obstacle to progress is Partisanship in Washington, i.e. powerful people’s inability to get along. Variations of this hallowed fable, and the whole extended family that makes up the “Too-Much-Partisanship” industrial complex, are found all over Capitol Hill, cable news, and throughout all of the nation’s papers of record. It’s the rationale behind plenty of ludicrous astroturfed initiatives undertaken by political staffers upon their retirement. It’s the subtext of every breathlessly-written cover story proclaiming a dangerous new era of polarization and warning us about the threat posed by populist demagogues.

For their part, politicians themselves, supposedly the greatest culprits in fostering a hyper-partisan environment, frankly can’t seem to stop decrying it and declaring their intent to put differences aside in the name of bipartisanship and some idealized common good that always seems just out of reach. Democratic Senator Amy Klobuchar wants to “bring back bipartisan talks” on healthcare. So does Republican Senator Lamar Alexander. So does Donald Trump! Paul Ryan and Nancy Pelosi, in a joint interview, proudly informed the public that “most of what we actually pass is bipartisan,” with Pelosi lamenting that “what’s newsworthy is what is controversial.” Calls for bipartisanship are the background noise of institutional American politics, perpetually emanating from the Beltway in a dull, ceaseless drone.

The basic story generally goes like this: ordinary Americans are fed up with the petty squabbling that dominates DC. Reckless partisanship prevents compromise on the issues that matter and most people, who are manifestly non-ideological (whatever this entails), simply want to see their out-of-touch political representatives work across the aisle for a change. Brinksmanship prevails and nothing, so the expression goes, “gets done.”

This trope, at once tired and ubiquitous, hinges on the idea that most people share a common set of desires and values and could agree on things if only the gosh darn politicians and talking heads would stop stoking division. There are no unbridgeable divides, only needlessly inflamed rhetoric. Politics is not a contest of right and left, rich and poor, insiders and outsiders, exploiters and exploited, just a meritocracy of discourse and ideas. This was the message that first landed Barack Obama in the national spotlight, with his 2004 “Red America, Blue America” speech. It was Jon Stewart’s core message during 2010’s Rally to Restore Sanity, which he framed as being about “tone, not content.” It inspired the almost satirical “No Labels” initiative undertaken by former Bush and Clinton advisors David Frum and William Galston, whose great emancipatory battle cry to the restless masses was “a grassroots answer to gridlock.” More recently, it provided the backdrop for center-left think tank Third Way’s bizarre safari into Trump country—a multi-city “listening tour” that will probably be cited by subsequent generations of sociologists as a case study in confirmation bias. (Their chief finding: ordinary Americans want Washington to Put Aside Differences And Get Things Done.)

The bipartisanship fable is one with a real, if superficial appeal. For one thing, one part of its critique is true: the talking heads on cable news clearly do spend a lot of time stoking division for its own sake and tying themselves into knots to defend their chosen side. But it also offers temptingly simple solutions to what ails American politics: if powerful people’s lack of collegiality and compromise is the problem, the fixes are obvious. Washington’s grownups merely need to pull up their sleeves and use their indoor voices; cable news pundits need only become a bit less shrill; campaign cycles less reliant on attack ads. Then we could reach the hypothesized bipartisan promised land: a place where most people agree on all the big questions and every national debate is as high-minded as a friendly joust at the Oxford Union.

And all of this could come about while changing absolutely nothing about the fundamental structures underpinning America’s politics or economy.

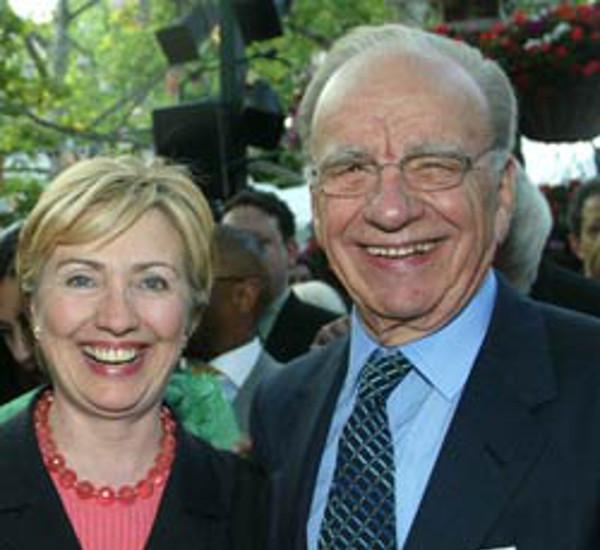

The most glaringly obvious hole in the anti-partisanship story is that those at the top of American politics and culture already, often visibly, get along pretty well. They exchange banter at the same awards dinners, appear on the same late night talk shows, occupy the same area codes, and tend to pay the same, criminally low, rates of income tax. They even enjoy the same shitty musicals.

Despite the supposedly unbridgeable chasm of the partisan divide, examples of elite chumminess abound. Only four short years ago, Ivanka Trump was fundraising for Cory Booker. Samantha Power, who once harshly criticized Henry Kissinger’s human rights record, joined him at a Yankees game and accepted an award in his name. Just days after they’d exchanged fire over the value of black lives on national TV, the Daily Show’s Trevor Noah was sending Tomi Lahren (who compared Black Lives Matter to the KKK) a conciliatory batch of cupcakes. The legendary “Notorious RBG” was, of course, close friends with Antonin Scalia, whose recent posthumous book contains a gushing foreword from Ginsburg on how “some very good people have ideas with which we disagree.” Van Jones, who was supposedly too much of a radical leftist to serve in the Obama administration, has just penned a book on how to “come together,” a philosophy he has practiced by taking gleeful selfies with Eric Trump. All of the ex-presidents, Republican and Democrat alike, are close friends. (Except for Jimmy Carter, whose preference for building houses for poor people over attending golf tournaments has earned him a reputation as an “annoying cuss.”)

The 2016 presidential election, which supposedly brought to the surface a uniquely divided America, is perhaps the perfect case in point. Prior to their formal political rivalry, the Clinton and Trump families enjoyed a friendly relationship for over a decade, the former infamously attending the latter’s wedding in 2005. Even the election and its aftermath have failed to fully corrode these bonds. Mere hours before her shock defeat, Clinton made it known that she hoped to patch things up with Trump—a man who’d threatened to “lock her up” and who she and her supporters had routinely characterized as an existential threat to the republic itself. (Their daughters, incidentally, also vowed to continue as “good friends” and last August, Bill, Hillary, and Tiffany Trump were all cordially invited to the wedding of Sophie Lasry, the daughter of hedge fund billionaire Marc Lasry.)

Such camaraderie might be a bit less nauseating if it weren’t emblematic of something deeper and more insidious.

It should come as no surprise that people closest to the center of power are often the ones fondest of extolling the virtues of bipartisanship and consensus. This is, after all, more or less the reality many of them already inhabit, and the one they more or less need to inhabit if they want to be upwardly mobile—genuinely controversial ideas are unlikely to get you a promotion. The Beltway may not be a place of total agreement—the range of acceptable opinion does, after all, span the vast expanse separating Paul Krugman and Ross Douthat—but it’s certainly one where internal conflict rarely has serious consequences for those directly involved. Debates with outcomes that potentially affect millions of lives can provide raw material for jocular cocktail chatter at the nearest capitol bar or even become an occasion for the affable exchange of baked goods. Friendships may be strained, prestige may be lost, and members of the two competing political and cultural tribes may have to trade offices every few years, but the price of failure for those at the top still tends to be a teaching gig in the ivory tower, a lucrative job in lobbying or finance or, in the worst case scenario, a multimillion dollar book deal from Simon & Schuster. Even the most loathed former presidents can be afforded the equivalent of secular sainthood, so long as their successors prove to be even worse. Given the stakes, we can understand why bipartisanship is so appealing.

In identifying the source of this pathology, though, we risk overlooking its most glaring contradictions and most dangerous implications. In the wake of Trump, high profile Democrats have taken to evangelizing bipartisanship in increasingly absurdist fashion. After the Republican Senate passed its robber baron tax package in December, a lachrymose Chuck Schumer took to Twitter to lament “what could have been” describing tax reform as “an issue that is ripe for bipartisan compromise” (Schumer has long favored massive corporate tax cuts), while the Democratic Party’s official Senate account praised Ronald Reagan’s approach to tax policy. Despite a sweeping victory over Republicans in Virginia, newly elected Democratic Governor Ralph Northam is now preaching bipartisanship (“Virginians deserve civility…they’re looking for a moral compass right now”) and exploring ways he can work with those across the aisle to reduce spending on Medicaid. In a recent intervention, one William Jefferson Clinton even issued the groundbreaking suggestion that Americans work to “expand the definition of ‘us’ and shrink the definition of ‘them.’” Pass the sherry.

Bipartisan posturing of this kind would be absurd in a healthy democracy, even at the best of times—after all, one of the reasons we elect people is so that they can debate and disagree. If you’re not fighting with anyone, you’re not fighting for anything. But given the stated agenda of the current administration, not to mention countless other Republican-led administrations across the country, bipartisanship is perilous and counterproductive almost by definition.

One need only review a selected history of some “Great Moments in Bipartisanship,” when members of both parties came together to serve their shared interest in… expanding the American war machine and imprisoning large numbers of black and brown people.

Great Moments In Bipartisanship

—The 1964 Gulf of Tonkin resolution, authorizing use of conventional military force in Vietnam, leading to a war that killed over 1,000,000 Vietnamese people and nearly 60,000 U.S. soldiers (Senate: 88-2; House: 416-0)

—1994 Crime Bill, which expanded the death penalty, provided $10 billion in funding for constructing new prisons, and eliminated education programs for prisoners (Senate: 61-38, 54 Democrats in Favor; House: 235-195, 188 Democrats in favor, signed by President Clinton)

—1996 Welfare Reform Bill, gutting the social benefit system for poor families (Senate: 78-22, 25 Democrats in favor; ), signed by President Clinton)

—1996 Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, hastening the capital appeal process so that prisoners could be killed faster (Senate: 91-8, House: 293-133, signed by President Clinton)

—1999 financial deregulation bill, removing various kinds of federal oversight over investment banking activity (Senate: 54-44, House: 343-86, signed by President Clinton)

—2001 PATRIOT Act authorizing indefinite detention and warrantless searches (Senate 98-2; House 357-66, 145 Democrats in favor)

—2002 Iraq resolution, granting the authority to George W. Bush for the war that killed 500,000 Iraqis and created 800,000 Iraqi orphans (Senate 77-23, 29 Democrats in favor; House 297-133, 82 Democrats in favor)

—2017 Senate resolution affirming Israel’s right to full control of Jerusalem as its capital in violation of overwhelming United Nations consensus (Senate: 90-0). Unqualified support for Israeli militarism and occupation may be the single most bipartisan issue of all; it was Chuck Schumer who advised Donald Trump to move the U.S embassy to Jerusalem. And let’s not forget the more than a dozen Democrats who signed on to a measure to criminalize the BDS movement.

—2017 House approval of a $700 billion defense spending bill, the highest ever, which Forbes said made “Trump’s [massive proposed military budget] look positively reasonable in comparison” (60% of House Democrats in favor)

Despite some obvious areas of discord, then, it’s not as if American elites have spent the past several decades disagreeing, cordially or otherwise, on a particularly massive scale. Both parties have largely promoted a corporatist agenda and their respective leaderships have been united in their mutual support for policies of unending war, mass incarceration, means-testing, and privately-administered, for-profit healthcare. The same plutocrats bankroll everyone’s reelections: even the Koch brothers have given hundreds of thousands of dollars to Democrats. Hedge fund managers vastly preferred Clinton over Trump, and Wall Street can go back and forth depending on who seems marginally more favorable to their interests. (They adored Obama in 2008, but switched to ex-private equity executive Romney in 2012.)

When the existing consensus is oppressive and exploitative, bipartisanship is simply partisanship for an unjust status quo. Put another way, the operating premise of those who promote bipartisanship is flawed. The problem isn’t that elites are so acrimonious they can’t agree or forge a consensus, but rather that they continue to be harmonious enough to do both, often with devastating consequences.

Bipartisanship of this kind is the reason tens of millions of Americans still can’t afford healthcare and why so many elections are ultimately bought and sold rather than won or lost. It’s how Washington elites from the centre-left to the centre-right can look upon a country where thousands of people die every year because they can’t afford to go to the doctor and quite earnestly believe the remedy is another wretched compromise between the federal government and the (almost literal) bloodsuckers that are private insurance firms. It’s the process through which Americans have found themselves engaged in destructive, open-ended war, and the reason that debates about military intervention invariably revolve around how to prosecute it most competently rather than whether to prosecute it at all. It’s why the country’s public schools and infrastructure are allowed to crumble while trillions in subsidies go to terrifying genocidal gizmos that would give Dr. Strangelove pause. It’s why wealth inequality is soaring while wages continue to stagnate and why prisons are overflowing with the poor, racialized, and mentally ill while rapacious bankers are deemed too big to jail.

And it’s how, in the midst of all of this, it remains possible, indeed downright respectable, to believe that the biggest obstacle to a decent society is bad manners.