Cetacean Needed

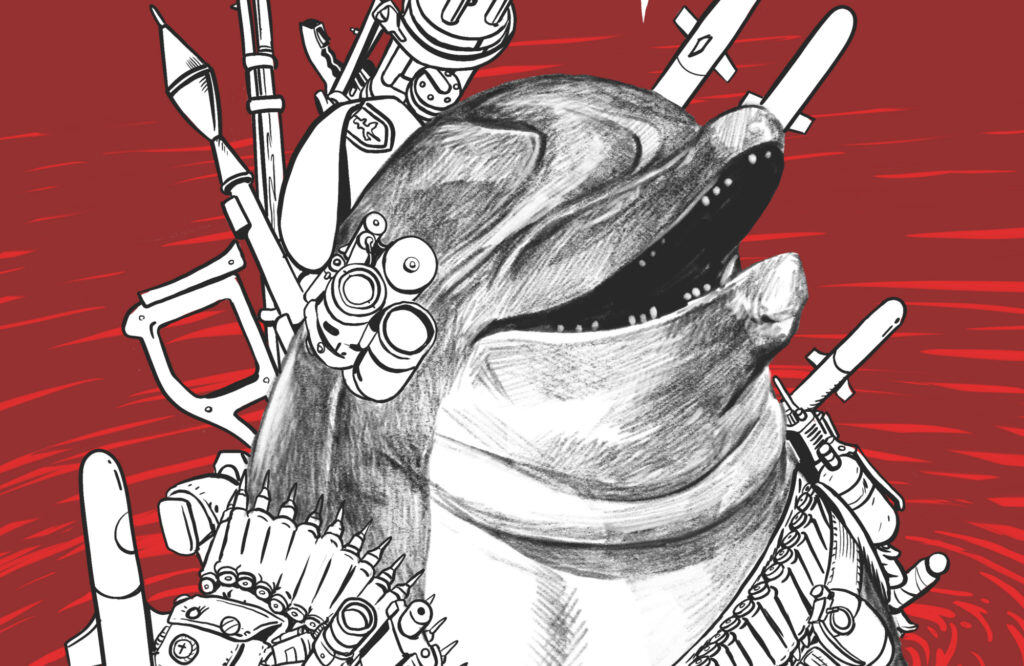

The “battlenose dolphin” and other militarized marine life.

“On the planet Earth, man had always assumed that he was more intelligent than dolphins because he had achieved so much—the wheel, New York, wars and so on—whilst all the dolphins had ever done was muck about in the water having a good time. But conversely, the dolphins had always believed that they were far more intelligent than man—for precisely the same reasons.” —Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

In May 2019, it was reported that a beluga whale had appeared off the coast of Norway, and was behaving very strangely. The whale had been pestering some fishing boats, demanding the attention of its crew, and the fishermen had the strange sense that it was trying to tell them something. The whale didn’t seem unhappy, exactly—it was clearly very comfortable with human contact, and enjoyed being fed and petted, even showing off a few tricks—but this was clearly no ordinary animal. Observers noticed it was wearing some kind of harness, upon which you could mount some sort of equipment; a camera, perhaps, or a weapon. The harness read “Equipment St. Petersburg.”

The whale was reported to the Norwegian police force, and as far as we know is still in custody. (Although Norway has a reputation for being somewhat liberal on matters of criminal justice, police custody is still police custody, and we hope the whale has been made aware of its rights and given access to counsel.) Rumors abound that the animal had escaped from a Russian military facility, and was in fact a spy that had defected by crossing the few miles into Norwegian waters (whales, being highly intelligent creatures, reject the concept of national borders). This is not as absurd as it might first sound: Marine mammals have long been recognized by humans for their trainability and ability to understand relatively complex concepts, as well as their cuteness, which gives them a layer of plausible deniability as they swim from territory to territory—one would be suspicious of a submarine making its way towards one’s borders, but who would suspect a porpoise? These characteristics make them a highly valuable resource for humans, and especially for human governments looking to intrude upon and destroy other human governments. To that end, several states throughout the 20th and 21st centuries have invested in military research and training programs for marine mammals.

The U.S. Navy prefers to use bottlenose dolphins and California sea lions. (Can’t be having any suspicious foreign cetaceans in the program—what if they turned out to have loyalties to foreign waters? American cetaceans protecting American citizens, that’s the way to go about it.) The Navy initially started studying dolphins in the 1960s, not with the intention of training them but to examine their bodies and the way they move, in the hope of improving the designs of their torpedoes. While these studies didn’t turn out to be very useful, the researchers involved found themselves fascinated by the dolphins’ clear signs of intelligence and willingness to be trained, as well as their ability to sense far-off objects in the water using echolocation. To this day, off the coast near San Diego, dolphins and sea lions are being trained to recover lost objects, detect sea mines, and warn navy personnel of intruders. In decades past, the Soviet Union had a similar program, resulting in a much more low-stakes and adorable subset of the Cold War arms race. The idea of military dolphins even inspired a 1973 thriller movie, The Day of the Dolphin, whose plot revolved around military dolphins being trained to assassinate the President of the United States by planting a mine on his yacht. (The U.S. Navy denies they have ever trained dolphins to plant explosives on boats, claiming it is impractical.)

These military training programs were not the first attempt by humans to exploit the potential of marine mammals. In the mid-1950s, a scientist named John C. Lilly began looking into the brain structure of dolphins, and in particular the way they communicated. He was partly inspired to study this by spending long periods in “isolation tanks,” closed capsules where he could float in salt water, disturbed by neither light nor sound, just him and a facsimile of the sea. As with many of the mid-20th century’s wackier ideas, he was also inspired by psychedelic drugs.

Lilly became convinced that bottlenose dolphins could mimic human speech patterns, and concluded that, given the right learning environment, communication between people and dolphins was within humanity’s grasp. He published a book in 1961, Man and Dolphin, speculating that dolphins would not only be able to learn human languages, but could also one day have their own chair at the United Nations, from which they could give a much-needed non-human perspective on international affairs. (Presumably, this chair would have to be submerged in some type of pool, or perhaps would be less a chair than a sort of aquatic playpen.)

This may all sound ridiculous in hindsight, but science had developed so rapidly in the previous decades that such propositions were taken quite seriously. If humans could make the atom bomb or travel into space, why couldn’t they talk to animals? NASA and several other U.S. government agencies invested in Lilly, who began making plans for a new and ambitious type of custom-built lab. (The same year Man and Dolphin was published, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union launched their first successful manned space missions; NASA took particular interest in Lilly’s theories because they suspected it would be relevant if they ever needed to communicate with extraterrestrials.) On the Caribbean island of St. Thomas, he had a house built and partially flooded with water.

This “dolphinarium” was designed for dolphins and humans to live in together, on the assumption that long-term cohabitation and exposure to human language and lifestyle would help the dolphins to learn English. Margaret Howe Lovatt, an amateur dolphin-science enthusiast who had assisted Lilly with some of his earlier experiments, was hired to live in the house with three dolphins for two years, playing with them, sleeping near them—in a bed suspended above the water—and speaking to them slowly and emphatically, as one would with a baby on the verge of their first words. Interestingly, Lilly did not express much interest in the other side of the coin, namely the potential for humans to learn the language of dolphins. All the focus was on getting the dolphins to put in the effort. It’s debatable whether we’re the smartest creatures on the planet or not, but we’re at least smart enough to try and get other species to do all the hard work for us.

After a while, the dolphin experiments took an uncomfortable turn. The sole male dolphin became sexually aggressive towards Lovatt, and the experiment became notorious after a story was released in the pornographic magazine Hustler that revealed Lovatt sometimes gave the dolphin manual relief. (Lovatt has commented that she feels this aspect of the experiments was overplayed in the press.) Lovatt also clashed with Lilly over his decision to dose the dolphins with LSD, a decision which made her uncomfortable, and did not bring the team any closer to a breakthrough.

In the end, the experiments revealed little valuable information, and the dolphinarium was eventually decommissioned. Humans had failed to teach dolphins English. We would have to make do with teaching them to do acrobatic tricks— and, of course, enlisting them in our wars.

The Dolphin Obsession

Why are humans so fascinated by our squeaky wet friends? And not just fascinated, but desirous to give them a special place in our culture: simultaneously as friends, resources, even mystical spirit-guides? We treat marine mammals differently from most animals, even other animals that appear to be just as complex and intelligent, such as pigs and crows. An old cliché stalwart of the “bucket list”—the list of all the things a person wants to experience before they die—is to swim with dolphins. People listen to CDs of “whale sounds” to relax and fall asleep (or at least, they did for a period in the late 1990s, crowding the shelves of gift shops, music stores, and musty hippie businesses alike). We love to “ooh” and “aah” over marine mammals, and are heartbroken at the thought of their mistreatment—witness the success of the 2013 documentary Blackfish, the outrage over whaling practices, and the demand for dolphin-safe tinned tuna. Interestingly, this adoration of marine mammals seems to be common even among people who are not vegetarian or vegan, and would not necessarily consider themselves animal rights activists.

Our fascination with military cetaceans is the perfect example. We all readily accept the military use of animals throughout history. Hannibal marched over the Alps with elephants—yes, of course he did. We know all about the horse’s central role in most human warfare, about carrier pigeons, about Navy SEAL dogs in Afghanistan with titanium teeth. (The titanium teeth aren’t weapons, they’re just dental crowns for doggies with tooth issues.) Run of the mill! We might know about Corporal Wojtek, the Syrian brown bear enlisted as a private and then promoted in the Polish Army. He helped his unit carry heavy ammunition. The unit then adopted, as their emblem, a bear holding an artillery shell. Ramses II supposedly had a pet lion that fought with him in battle. The Soviets trained suicide bomber dogs to climb under tanks with explosives strapped to their backs. The Greeks used flaming pigs in battle, and the CIA outfitted bats with explosives. There was one confirmed CIA project in the 1960s of implanting microphones and transmitters into cats to record conversations. (They may only ever have tried it on one cat, and that cat may have been hit by a taxi in its first field test. The CIA is tight-lipped on this question.)

The thing about humans at war is nothing is off limits. If we grind up ourselves and our children like so much grist in the war mill, why would we spare the animals? But there is still something special about whales and dolphins. The thought of a beluga strapped with spy gear still seems odd in a way that a cat with a microphone does not. Elephants are big, cute, intelligent, with complex social structures, but the notion of co-opting them to help us kill each other seems completely natural. But whales and dolphins? That’s weird. That’s somehow surprising. We love cetaceans, we alternately rejoice in and are horrified by their lives in captivity for our entertainment. Spending a few minutes in a pool with them is among many people’s lifelong ambitions. But using them for war doesn’t sit right.

There are a few different explanations for this obsession and accompanying discomfort of ours. First, there’s a term from the world of conservation that can help us understand this phenomenon: charismatic megafauna. There are certain types of animal that humans simply love, and attach a special value to: Think of elephants, pandas, tigers, rhinos. These are the animals from children’s books, t-shirts and posters; the animals world leaders give to each other as gifts (there are entire academic articles on China’s “panda diplomacy” alone). Conservationists have noticed that for whatever historical and mythological reasons, these animals get attention, and have responded accordingly by prominently featuring them in their campaigns. If you’ve ever owned any animal rights or environmentalist regalia—a badge, a decal—it probably had a picture of one of these “magic” animals. No-one’s putting a naked mole rat on their pamphlets.

There are some characteristics that seem to make some animals “better” than others in the eyes of humans. Charismatic megafauna are usually “cute” in some manner, whether by their appearance or their behavior, with complex social structures and habits at least somewhat comparable to our own, and are physically large enough that we can see their faces in detail, enabling us to humanize them. After all, how could we be expected to empathize with something that we can’t relate back to ourselves? Are whales and dolphins simply the most charismatic of the megafauna?

Humans also seem to have a particularly obsessive relationship with the sea, and the animals within it. Oceans take up 71 percent of space on the planet, and yet at a time where we’ve made our way across pretty much all the land, we still cannot populate the ocean, or really even know what’s in it. Google “deep sea fish” and look at what eldritch horrors lurk in the areas too dark and pressured for humans to survive—strange and unsettling creatures with uncomfortable shapes, haunted teeth, unforgivable eyes. Consider the “bloop,” a mysterious ultra-low-frequency sound first detected in 1997 emanating from somewhere in the Pacific Ocean. Or, of course, read Moby Dick, the most famous man-versus-nature story in all of Western literature. Having this entire arena of the earth that we cannot completely discover seems to drive us wild, especially since it’s populated by creatures who are, like the ocean itself, friendly, useful, and yet still unknowable.

But amid this last great frontier, this unknowable universe of leviathans, thresher sharks, slime eels, immortal jellyfish, tiny adorable octopuses with enough venom to kill several adult humans, we’ve long seen whales and dolphins as allies. St. Martinian was an early Christian hermit who could not keep the ladies away. Attempted seductions on the mainland drove him to live on a rocky island, but even there he couldn’t escape. A ship beached on his island and a woman came ashore. Naturally, in response, Martinian leapt into the ocean. He would have drowned if not for being carried to land by two dolphins. Jonah, of course, was saved by a whale on orders from God. Arios was a wealthy Cretian lyre player whose crew turned on him while at sea. He played one last song before leaping into the ocean, and was rescued by a pod of dolphins who liked his music.

In fact, dolphins don’t just save us, in many origin stories they are us. The Chumash people in Southern California consider dolphins to be siblings. They have a creation myth in which the Earth Mother created people on Santa Cruz Island. But eventually the island got crowded and noisy, and she got annoyed. So she made a rainbow bridge to the mainland and asked them to leave. While crossing on the rainbow bridge, some people looked down, got dizzy, and fell into the ocean. Rather than letting them drown, the Earth Mother turned them into dolphins. The Santa Barbara Channel is still populated by thousands of dolphins today.

There are actually lots of dolphin creation myths where people are saved from drowning by becoming dolphins. In a story from Chinese mythology, a princess and her abusive stepfather were crossing the Yangtze when a storm rolled in. She jumped into the water to escape and transformed into a river dolphin. He also went into the drink and became a porpoise. And back in Greece, Dionysus was once kidnapped by pirates. He drove them mad with hallucinations until they jumped into the sea. But, considering them sufficiently repentant, Dionysus saved them from drowning by turning them into dolphins. Meanwhile Apollo turned himself into a dolphin to commandeer a merchant ship and its crew as the first staff of his temple at Delphi. All praise Apollo Delphinus.

The Ever-Present Horniness

And aside from being our close relations, dolphins have long made us horny. Amazon river dolphins sometimes transform into attractive humans at night to seduce men and women alike. Even the story above about Margaret Howe Lovatt masturbating her dolphin companion might reveal more about us than it does about her. After all, there are whole industries of animal breeders whose entire job is giving various animals orgasms. There are also plenty of guides to owning certain pets that recommend getting them off once in a while. What does it say about us if we react more viscerally to helping a dolphin masturbate than to manually stimulating a cow’s prostate? Do we protest too much?

Maybe all of our conflicting feelings about cetaceans go back to the unique combination of proximity and distance. They’re mammals like us, social like us, with complex communication systems like us. They play like us and enjoy sex like us. But we have spent most of our shared history with very few opportunities to learn much about them. They come up to eye us once in a while but mostly live in a world that’s not ours. We can find and follow and observe a herd of elephants for entire lifetimes, but a dolphin or whale can shake us with a deep breath and a few kicks of its tail fin. Not only are they hard to follow, they’re hard to catch and to keep alive. The first recorded dolphin or whale kept successfully in captivity was a beluga owned by P.T. Barnum in the 1860s. He caught five but only one survived, and only for two years. The first cetacean wasn’t born in captivity until 1947. So even though our shared narratives reach back thousands of years, we’ve only been up close and personal for a very short time.

Unfortunately this probably doesn’t bode well for the dolphins and whales. Public outcry might eventually close SeaWorld, but if the world’s navies decide that cetaceans can be useful, then we can only expect to see more mine-detection dolphins and camera-laden belugas. Then again, who knows. Maybe simmering species-wide self-hatred will forever prevent us from ending war for our own sake, but we’ll do it to save the whales. After all, they’ve been saving us for thousands of years. It might be nice to return the favor.